“I never, ever think about the future.”

Ten bored-looking models sat in a minimal interpretation of a waiting room, part Beckettian set part administrative lobby, surrounded by grey drapings, waiting for their ticket number to be called upon. This would trigger a clockwork-like series of events: a model would walk towards the right of the scene, an austere black-clad assistant would rearrange the presented outfit, update the numbers on his counter, and the model then posed for brief moment in front of a grey curtain. She would then take another ticket, and either sit back in the waiting area, or disappear behind the set, only to reemerge a moment later without any changes in her attire. The counter would go up by one, and the process would start all over again: an endless parade of the ten same silhouettes, the mechanical pointlessness of walking, posing, waiting.

Phoebe confirms that this was not accidental: “I wanted to convey a reflection or observation of what is happening at the moment within fashion; it’s literally going around and around and around, again and again, without ever stopping to look at itself.”

“The girls were in this cyclical closed system which just self-perpetuated without any question, it was a presentation about presentations and a presentation within a presentation, self-referencing and without seeming end. It wasn’t about boredom, it was about cycle.” You couldn’t blame anyone for confusing the two.

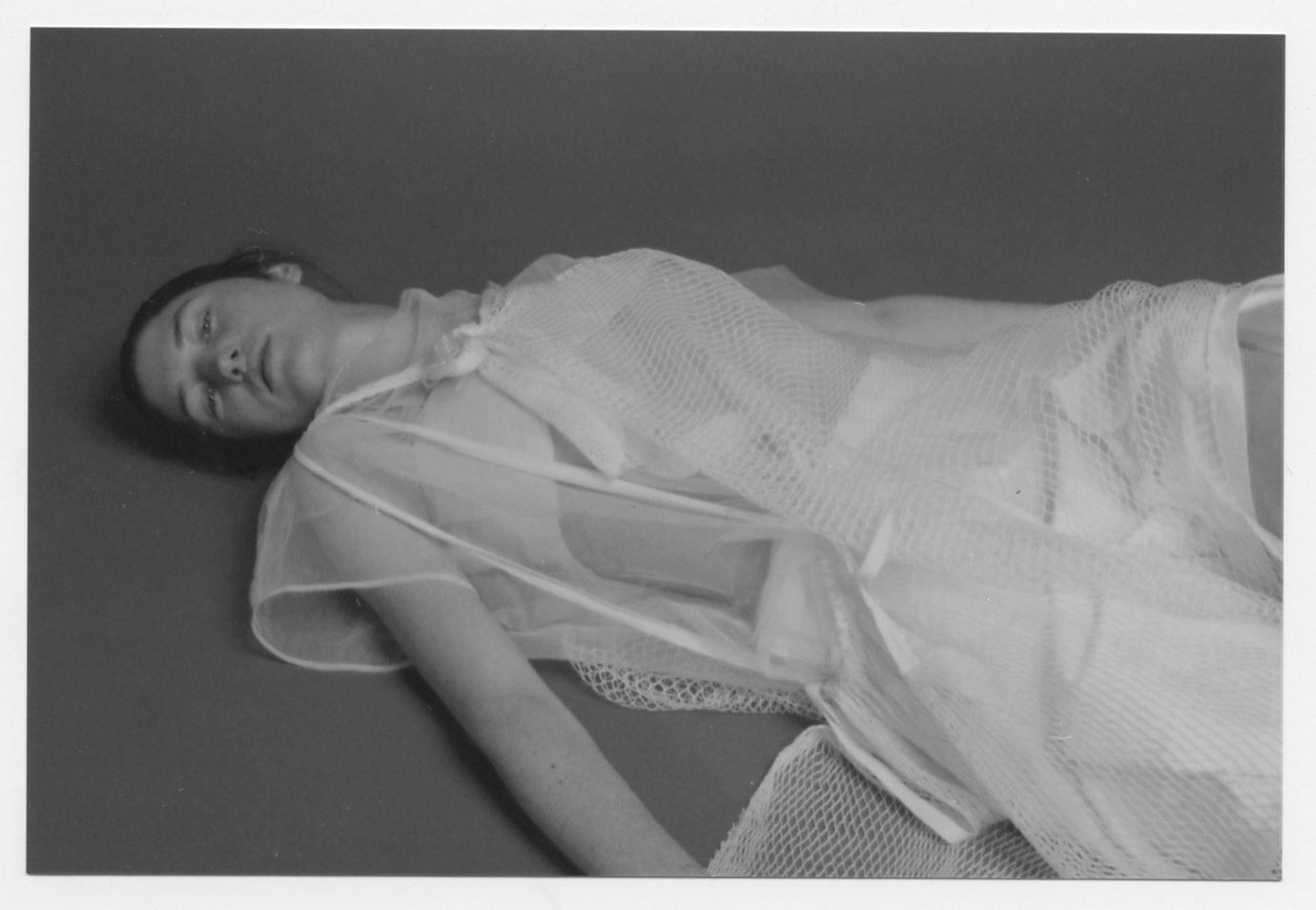

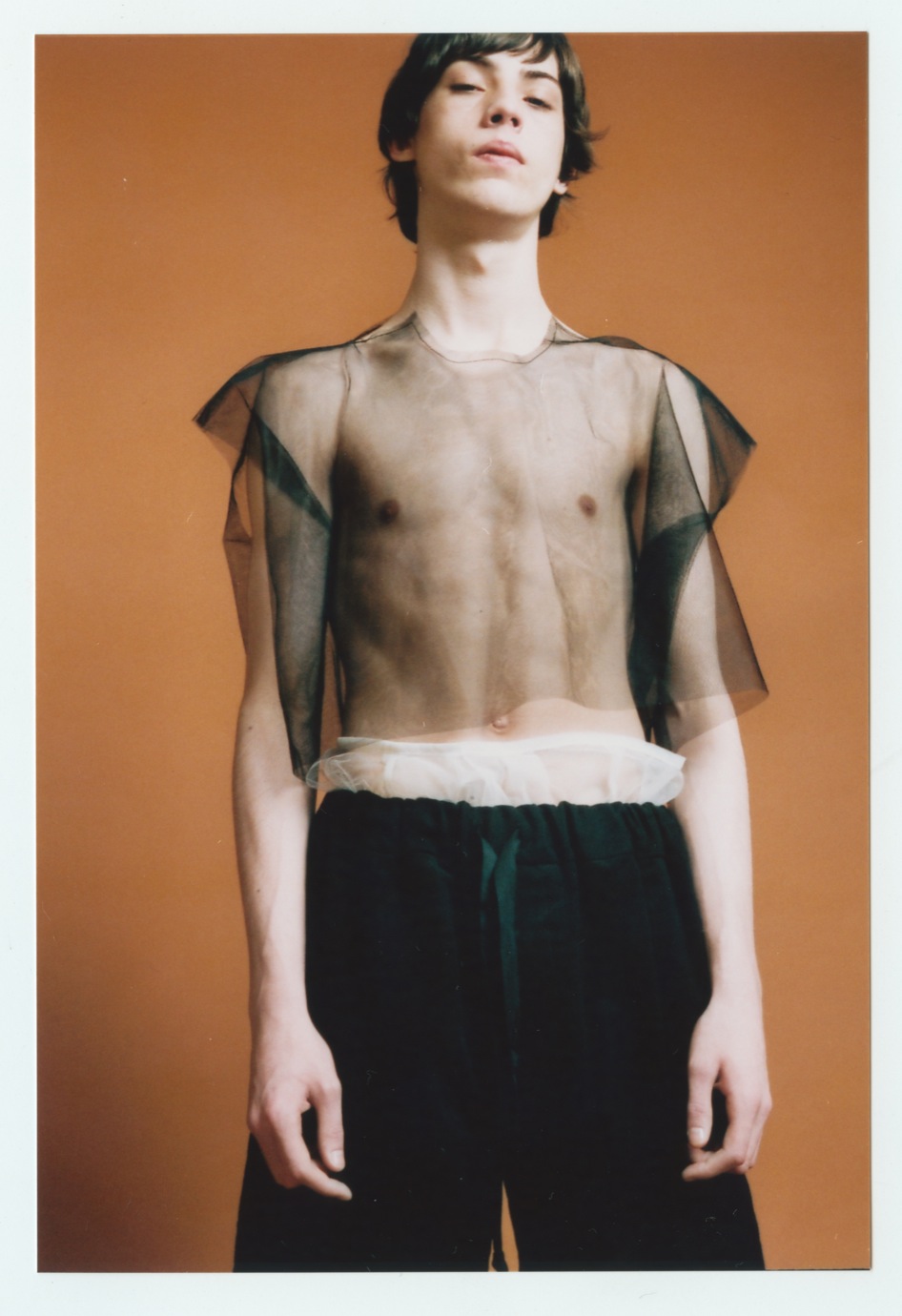

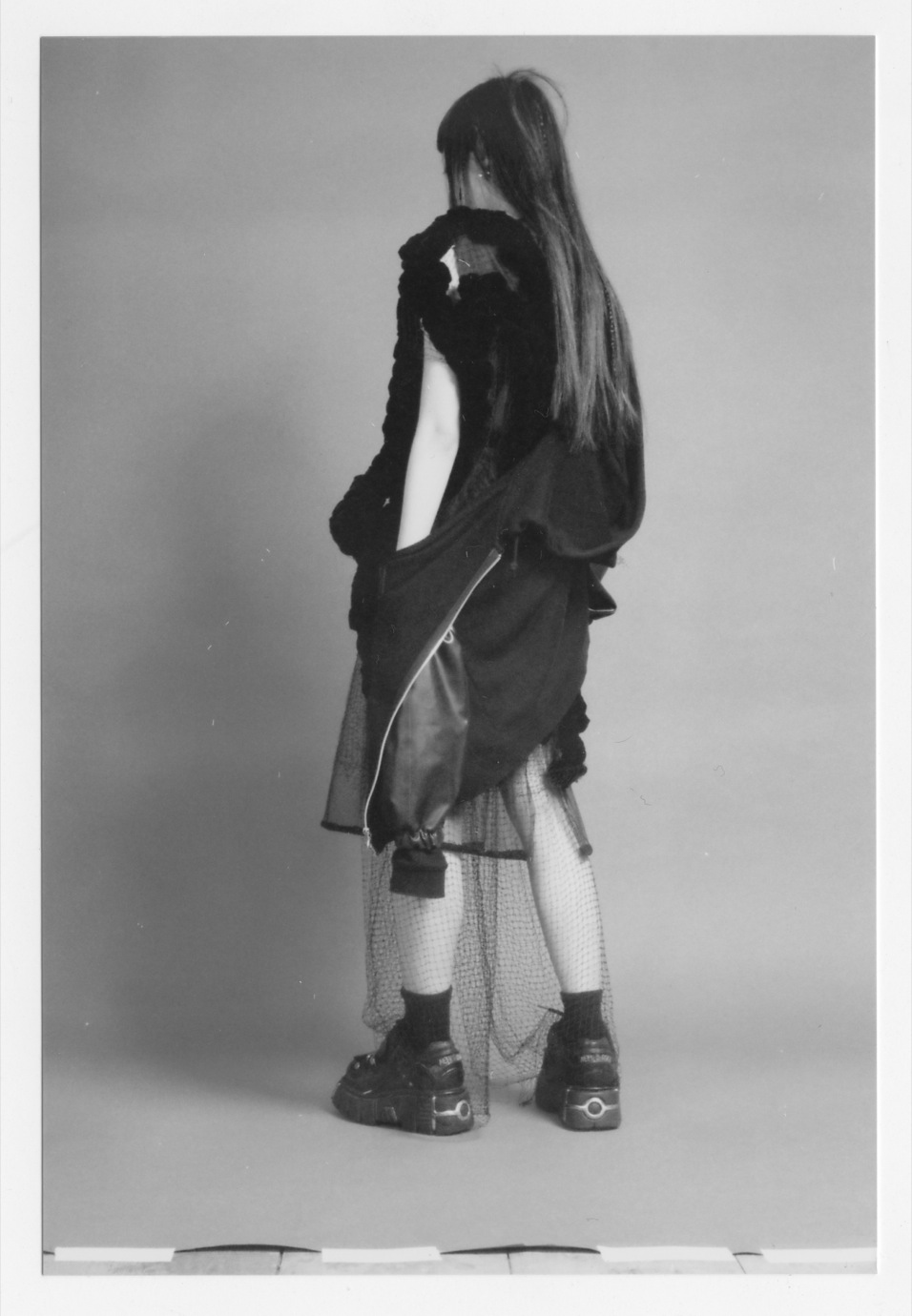

But if the presentation channeled cyclical ennui, the clothes had something subtler in mind. Phoebe extended on her work from the previous season by using hand-made embellishments such as the woven black and white panels — recalling television noise — that covered some of the outfits. This type of painstakingly crafted textures have very much become a signature for her brand, something she is actively seeking:

“I have worked with handmade woven textiles since the start of the label 10 seasons ago, originally it was about making a point about physically making fashion slower and doing it more thoughtfully. Making things with your hands rather than with a computer, against all the computer printed fabrics that had been saturating the fashion press whilst I was studying and I had got so fed up with seeing. It was about making things that were anti-machine and anti-speed, no matter how many nightmares and how much that affected the ease of my production time – that’s how important it felt at that time to make that point. All the articles I read with young designers in them when I was studying were focussing on how fast their businesses were growing and what celebrities were wearing them.” She adds: “I suppose that point is still a relevant one, so that’s why I’m still using this same technique.” Decorations of heavy black string, asymmetric shirts, hooded short coats and a red latex apron concluded a small and low-key collection. While there is an undeniable darkness to her work — she admits to “having a definitely dystopian leaning” — it is balanced by the sweet romanticism of her craft: “the hours spent in your hands gives the relatively plain material its sense of luxury, I like the transformation that can happen in these processes.” This is her strength: a poetic vision of deconstruction and reconstruction, an exploration of the humble beauty of craft through the discreet charms of textures. It is hard to picture a sweeter apocalypse.