“THERE’S SOMETHING ATTRACTIVE ABOUT BEING CONSTANTLY POSITIVE ABOUT THE POTENTIAL OF THE NOT SO DISTANT FUTURE.”

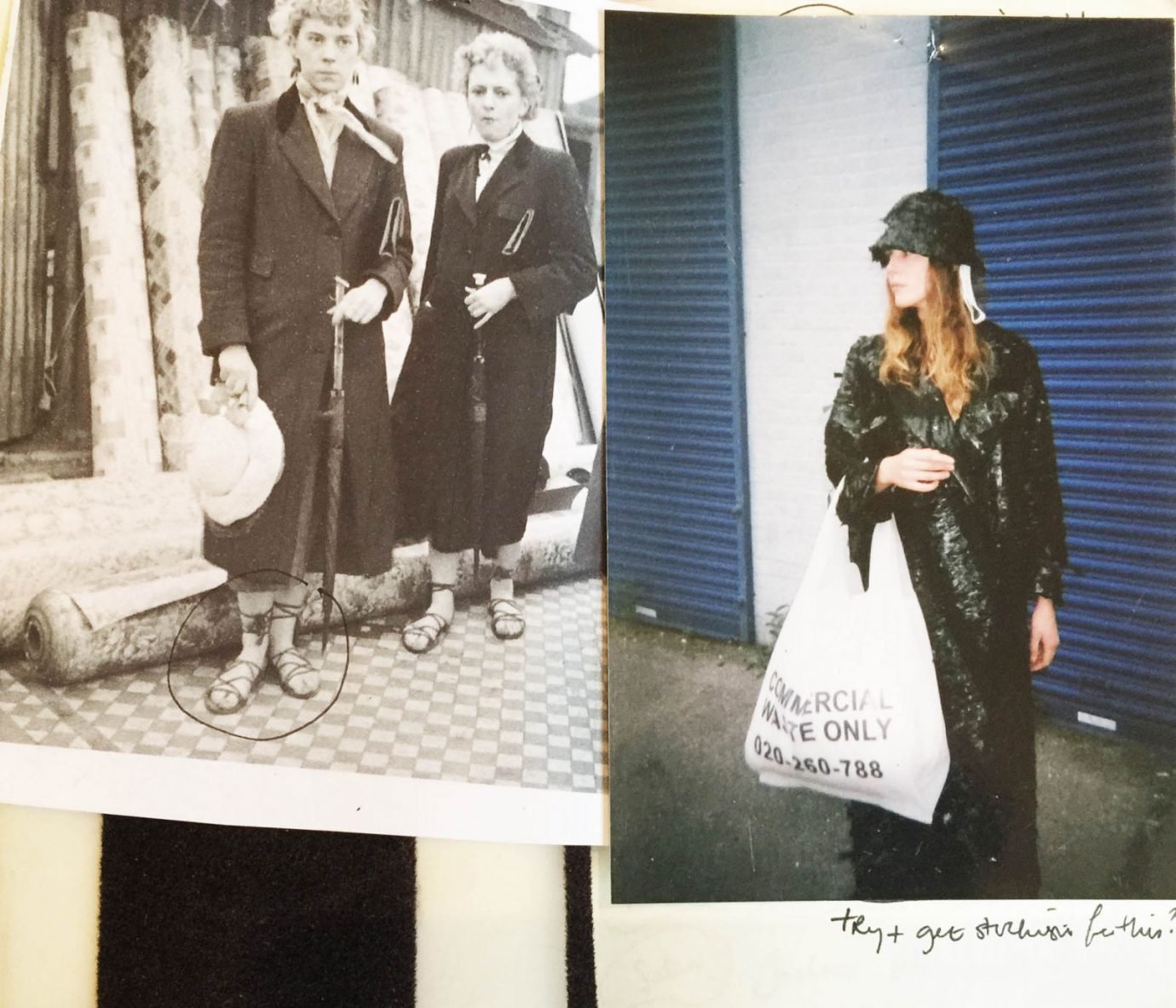

Without any formal training in art or design, over six months he worked through the night on a portfolio centred on dark notions of posture and bone diseases – a million miles away from what he does now, he says. The portfolio made Professor Louise Wilson OBE sit up and take notice, and thankfully so considering he didn’t apply to any other colleges. Under Wilson, whom Tait thanks for giving him space to develop his very personal collection, he struggled and almost failed the first year before finding his feet with an all-black final collection of streamlined separates elevated by precise tailoring, sculptural panels and swishes of rectangular streams.

“When I started at CSM the last thing I wanted to do was to start my own label and become a starving designer in East London, which is of course exactly what I went on and did,” he laughs. “I had this idea that I would go to this really famous school and have a great time and develop my interests, but in the first year I was freaking out and felt as though I had such a difficult time trying to develop a project and present and package my ideas in a Saint Martins way and it just came off as disingenuous. I was looking at other students and seeing how they were making portfolios – most of the students and my peers had gone on to do a BA in design at an art or fashion school with a foundation course or a gap year. Some people had been in fashion school for six years!”

Having moved to London with the support of student loans, the realities of being a fashion graduate soon kicked in after completing the course. “It was 2010 and we were in the midst of the recession and it was eight months or even a year before anyone got a paid job. Some people were graduating with BA and MA, having won some kind of award at school, and being offered an unpaid internship at a fashion house in Paris,” he recalls.

Part of the problem, says Tait, is the infinite amount of fashion graduates emerging from art schools, often carrying the burden of student debt that runs into tens of thousands. “There’s no other place where there are this many fashion colleges, which is a plus and minus in a way because when you think about it there’s over eight thousand BA womenswear graduates every year in the UK,” he says with a sigh. “When you think of how many jobs are available that will be able to pay your rent in London, it’s a dangerous position to be in and it’s a lifetime of debt. It was a big reality check for a lot of us. I realised there were literally no jobs. If someone handed me a contract with a great salary, I would have reconsidered and done that for a few years to pay off my student loans, but that wasn’t happening, so I had to keep myself busy and that’s how the wheel started turning.”

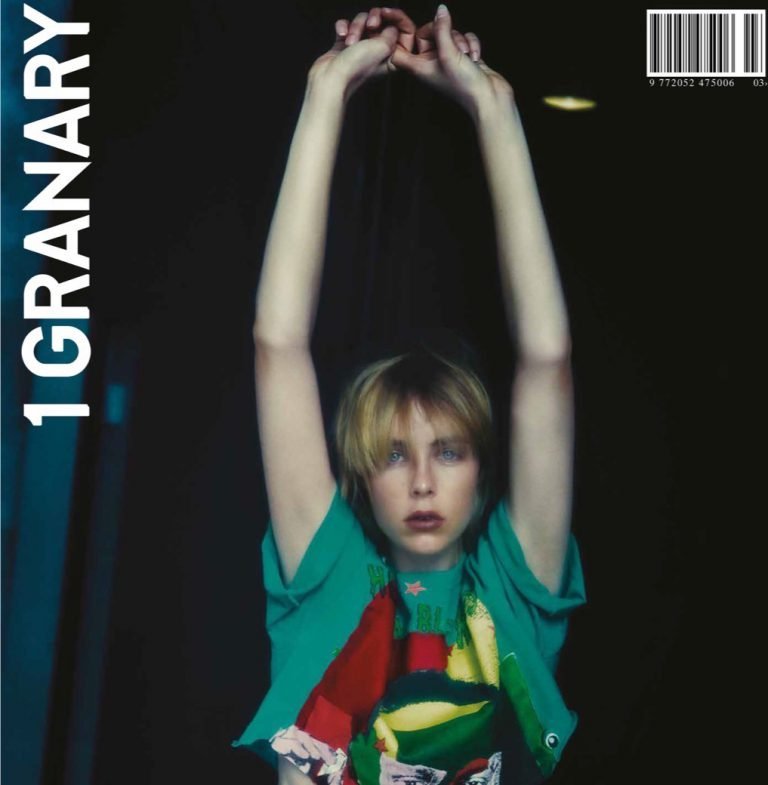

Thankfully that wheel has taken him far, and perhaps further if he had hired a business partner early on. He stresses that designers pairing with financial minds is a much more frequent occurrence in America: “You see designers there setting up brands because they want to own a brand,” he says. “In London, designers start labels because they’re designers by nature.” For Tait, being a designer entails much more than crafting a well-executed collection. One his most notable achievements has been to put on a show during London Fashion Week every season since starting his label, regardless of major financial throwbacks and constant compromises. Each one has contributed a considerable air of energy and excitement to the schedule, which is quite remarkable considering his shows are usually held on the same Monday as Christopher Kane, Burberry Prorsum, Roksanda Ilincic and Erdem.

“I’m a bit of showman in terms of how I direct my shows,” he says with a smile. “I’ve always designed and sketched the runway show while I was designing and sketching the collection, so it was difficult for me to separate the two. It’s a house for the collection; an environment. I’m also attached to the idea that what you see on the runway is what you want to wear – something that you can buy in a store rather than some kind of elaborate art project. I strive to see it all crystallise in that moment.”