“Yoga helps me to de grump,” said Axel after explaining how his 7am yoga session had been cancelled, leaving him stranded for an hour before our meeting. It was impossible to tell that Axel hadn’t had his de-grump fix, even if it was still only 9am. “I’m a morning bird,” he told me, “by the time the light goes out I’m not that creative anymore.” This creativity amassed itself at college in the German town of Bielefeld, where Axel studied Photography for seven years in a building occupied with aspiring graphic designers, fine artists and crafts people.

“I wonder if he’s as curious as his pictures…” I thought whilst waiting for Axel Hoedt, the German photographer who has spent the last 7 years capturing Europe’s traditional carnival goers in their spectacular and somewhat terrifying glory. His most recent book titled ‘Dusk’ catalogues the carnival people of Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, starkly shot moments away from the festivities. The images are unnerving to say the least. It was thus a surprise when a man to whom the adjective ‘jolly’ would most definitely apply arrived in an east London coffee shop (with stupidly loud music) to be interviewed.

“I REMEMBER US SITTING AT COLLEGE AND LOOKING AT THE REFLECTIONS OF ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE PICTURES; IF YOU LOOK CLOSELY YOU CAN SEE THE WHOLE LIGHTING SET UP IN THE REFLECTION OF THE EYES.”

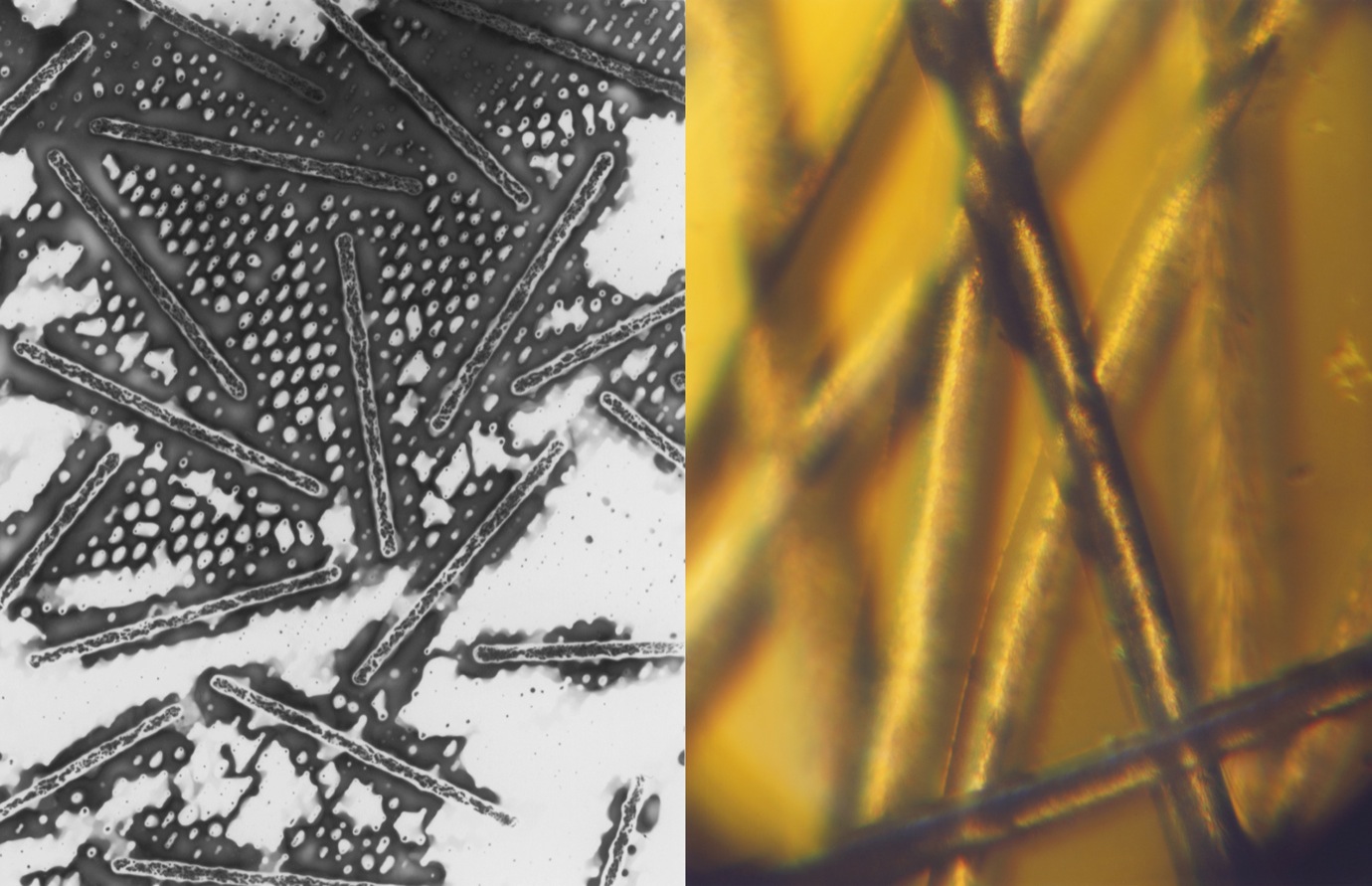

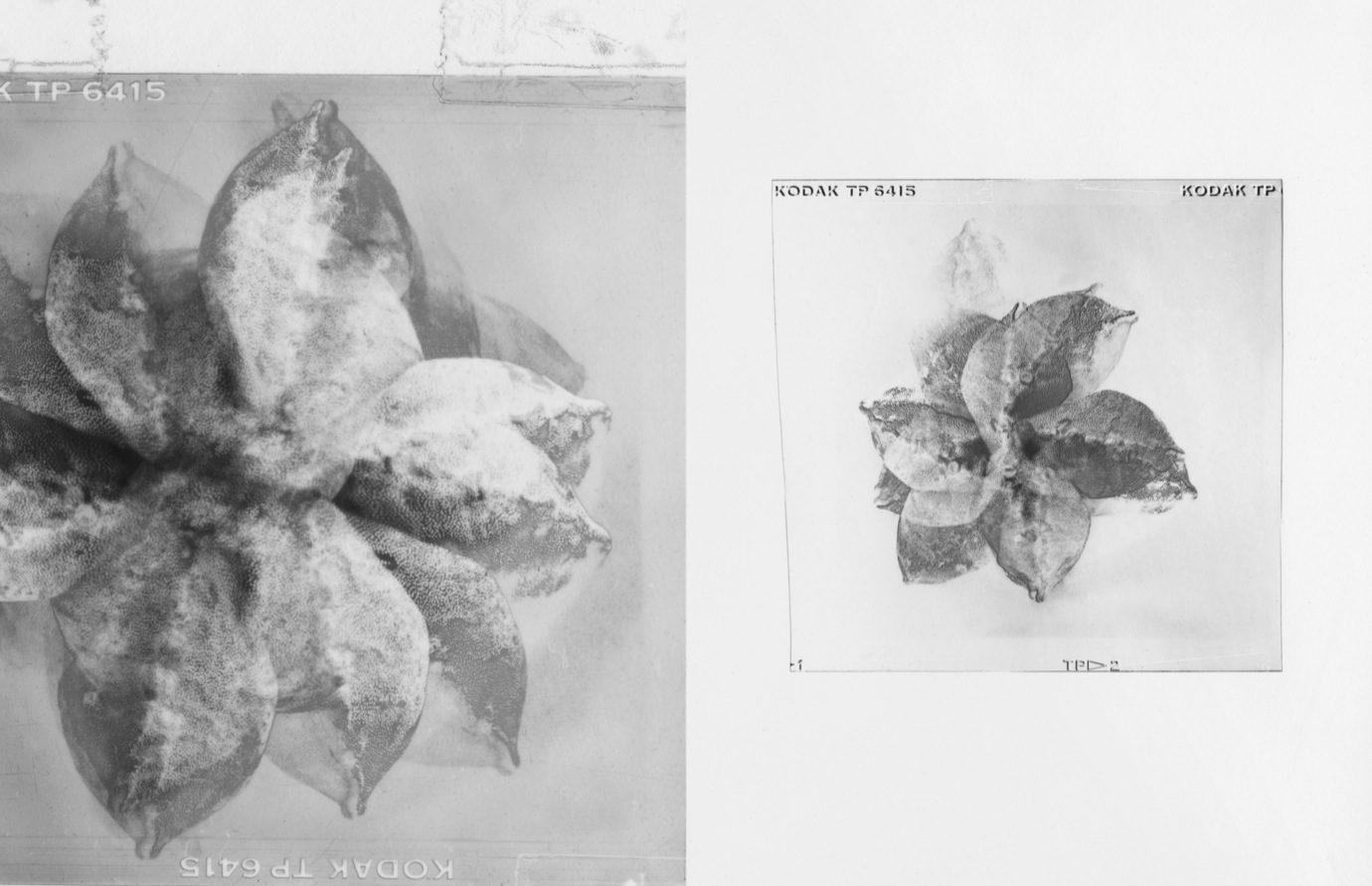

Axel’s schooling was a mixture between the artistic influences of his unconventional tutors and a fascination with fashion imagery. The work of his tutors was completely abstract. The course leader, Gottfried Jäger, grew to relative fame in the late sixties and seventies with a style of photography that formed repeated patterns of minute shapes and silhouettes. Jäger’s psychedelic processes lodged themselves in Axel’s mind, “I didn’t clock at the time how important it was!” he told me enthusiastically from the rather uncomfortable stools we were sitting on. Axel went on to hint that what he calls the ‘microscopic thing’ definitely-maybe has something to do with his next project. It wasn’t just the rewards of a multi lens camera which Axel found enticing; the pages of fashion magazines were just as arresting. “I remember us sitting at college and looking at the reflections of Robert Mapplethorpe pictures; if you look closely you can see the whole lighting set up in the reflection of the eyes. That was the way we tried to figure out at the time what sort of lighting they were using, because you had no clue.” The work of Mapplethope and other fashion image-makers played a huge role in shaping both Axel’s work and his ambitions.

“THERE IS NOT A BIG DIFFERENCE TO WHEN SOMEONE HAS A MASK ON, TO WHEN SOMEONE CLOSES THEIR EYES, TURNS THEIR HEAD AWAY OR HAS THEIR HEAD CHOPPED OFF. IT TOOK ME 30 YEARS TO REALISE THIS.”

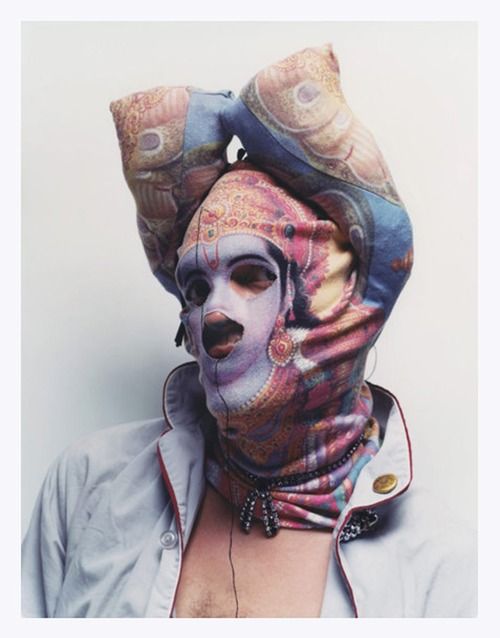

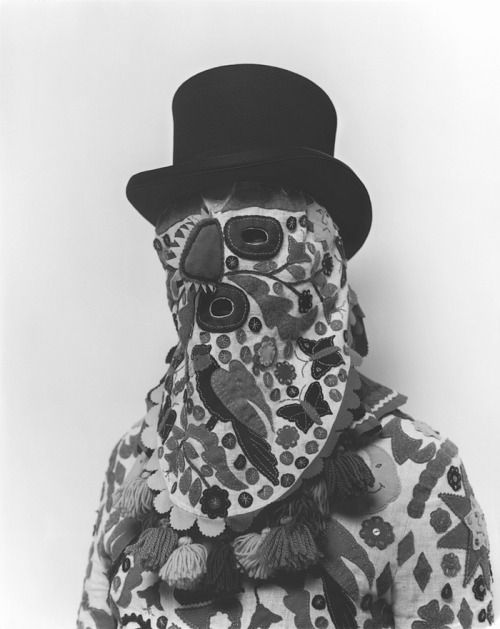

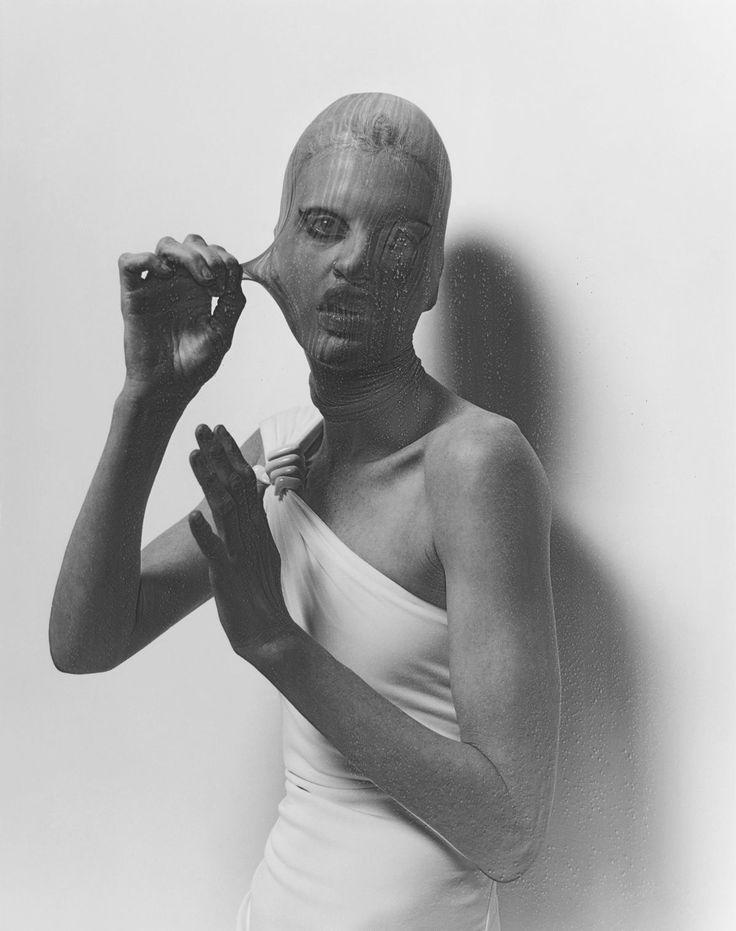

What is immediately apparent about Axel’s work is the strangeness of his portraits; “The portfolio I worked on to get accepted at school had hardly any people in there. I think there were only two portraits and their heads were cropped and shot from the back.” Fast forward twenty years and Axel is now capturing the faces (or part of the faces) of the likes of Kristen McMenamy to Sinead O’Connor, creating images that recognisably draw parallels with the distorted figures from his earliest work. For the non-seasonal fashion publication Archivist Editions, Axel was given full rein of the Hussein Chalayan archive. The series of images show Kristen McMenamy in a pillar-box red sculptural dress, her face sliced down the middle by a shard fabric, obscuring her right eye. But what about those startling carnival goers, where do they come in? “You can see it with Dusk and my previous book, there is not a big difference to when someone has a mask on, to when someone closes their eyes, turns their head away or has their head chopped off. It took me 30 years to realise this.”

Obscuring or concealing parts of the figure is more seriously explored in Axel’s two books, ‘Once a Year’ and ‘Dusk’, both of which document carnival goers. Coming from Staufen, a farm town in rural Germany, one might think that Axel would have been exposed to European carnival activity, and it’s true, he was indeed, but apparently not the right one. “I grew up with carnival, but I never thought it was exciting, because in the village where I come from the masks are completely boring and uninteresting,” he tells me, meaning no offense to Staufen. It wasn’t until Axel really started delving into the carnival underworld that he found a whole realm of mystifying costumes and creatures.

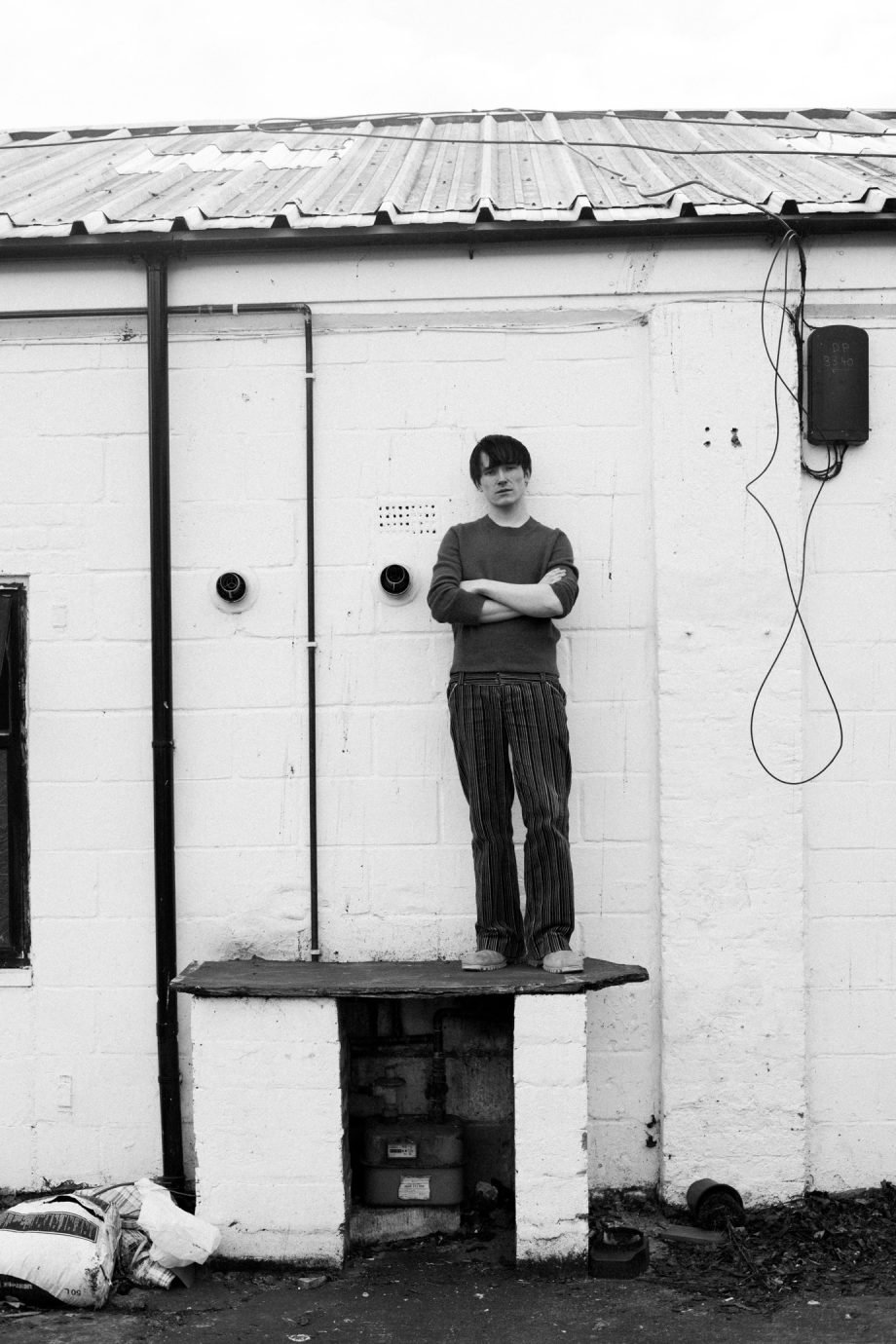

Milk maids, farmer’s wives and scarecrows, Axel’s photographs first and foremost document a community, however distorted it might look. “I had some villages where there were no bystanders, a small village where nearly everyone was participating. Then you wonder whom they’re doing it for, because no one’s watching. It’s for themselves, spooky huh?”

Looking to Richard Avedon’s ‘In the American West’, Axel removed a select group of characters from the festivities and hurried them into a variety of makeshift studios. “We used everything, whatever was there; if there was a community hall we could get into, we used that. If there was a dark back room of a restaurant, we used that.” A considered decision to remove people from the carnival scene and onto a white canvas really makes the photographs striking. “I took the characters out of that context and said: now just you on your own in your bird costume, stand there like you are waiting for the bus.” Although they definitely don’t look like they’re waiting for the bus, the costumes are given a new meaning once taken out of sight of the parade.

In Axel’s work disguise is everything…“What you choose to conceal yourself in says just as much about you as if you were wearing nothing at all,” Axel explains. Behind the facades there is still starkness to Axel’s photography, whether that be with a supermodel or an Austrian farmer. It’s up to the photographer to provide the balance between baring all and feeling secure: “I’ve got this big camera on the tripod, and then the other person is behind the mask, so each of us is protected.”