In December, we spoke about shoes being an object which you can challenge. Tell me about some of the ways in which you are doing this?

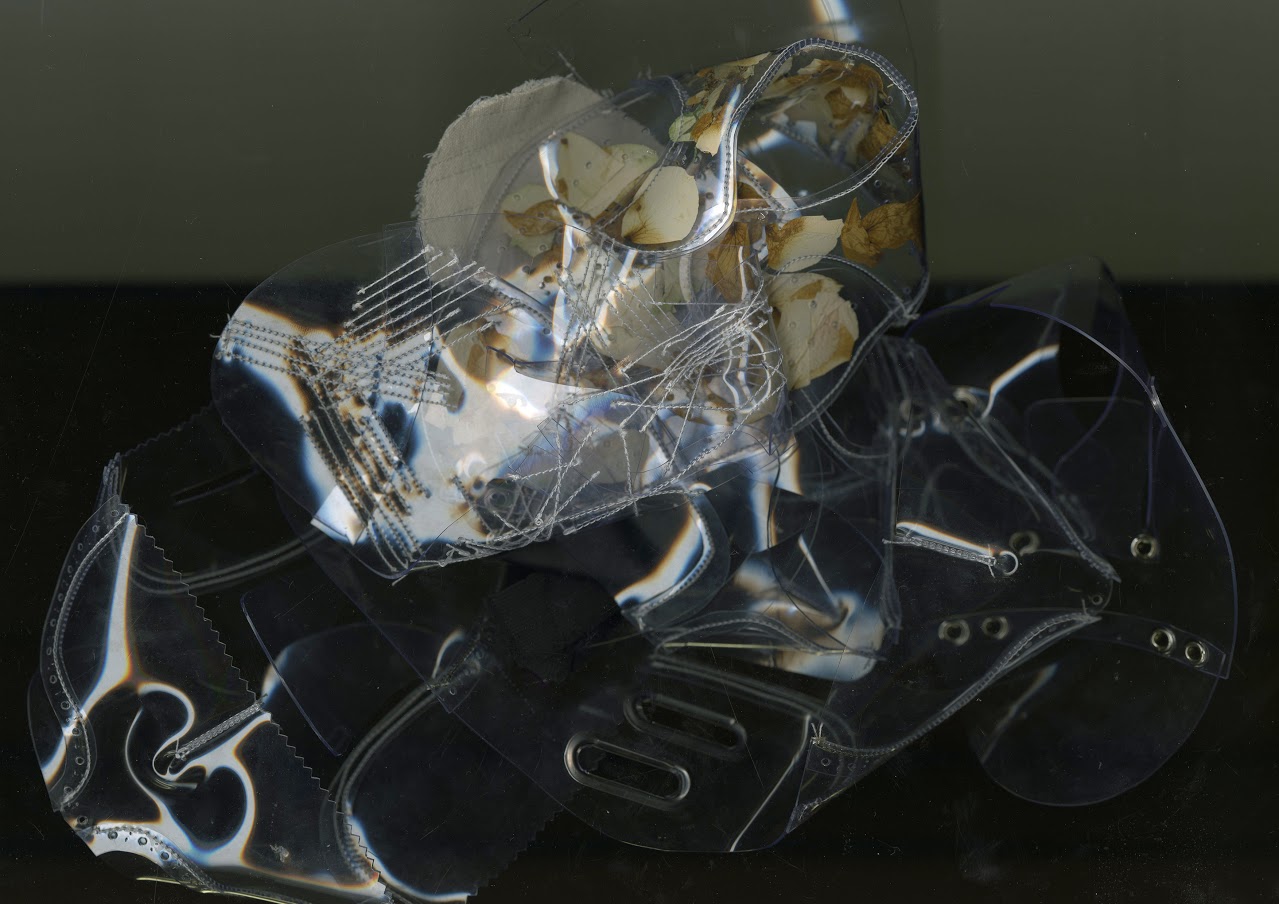

I always start from an assumption. For instance, shoes are objects that play a core role in the relationship between an individual and the world. It is the layer in between two major dimensions; therefore shoes are key in the dialogue between the self and the ground. They can change the posture of a person and their perception of reality. They can make somebody dream, or dance, or fall down! When I design, I always think about an ideal person, his values and what this person wants to communicate and experience in the world. What if a person wanted to jump instead of walk? Or walk on an asphalt street in a big city as if it were a grass lawn in the countryside? The endless degrees of interpretation drives my personal challenge about what footwear design can be.

You mentioned that you studied footwear at a school in Venice, which largely focuses on architecture. How did this impact your outlook?

Both shoes and buildings are integral to our lives, and both need structure to function. Whilst studying the BA in Venice, we were constantly encouraged to consider this dialogue. We were analysing the concept of the house — the idea of homo nobilis, and shoes being the ultimate ‘wandering house’. I really love how architect Adolf Loos thinks about shoes in his essay “Why a Man Should be Well-dressed: Appearances Can be Revealing.”

What drew you to study fashion? Are you from an artistic background?

I grew up observing people and what they looked like: the old lady with thick ankles at my mother’s salon, my cousin and his nylon coat, my friends and their low waist pants. I developed a natural interest in fashion, drawing on everything that intrigued me. At school I studied maths and science, and my practice before uni was mainly theoretical and self-taught.