You studied for your BFA in Louisville, where your practice was much more sculptural, could you talk a bit about that early work?

As a young artist I focused exclusively on drawing and photography until I reached college and finally discovered sculpture; it was the dimension I’d been missing, and the material playground I’d been longing for. From there I found glass: the most difficult material, but also the most enjoyable. Glass taught me to think and move differently, and how to get out all the physical frustration I’d previously had sitting still in front of a canvas. It taught me how to collaborate and contribute, how to work through stress and how to see process from beginning to end.

Then, an excellent professor showed me that concept could go deeper than I’d ever imagined. I began integrating themes from all of my favorite subjects including archeology, physics, mathematics, and human sexuality (which quickly became the foundation for almost everything I made). At the completion of my BFA, my work was reminiscent of ancient statues and gestures while I categorically manipulated sections of the human body. I loved the old gods of fertility and the ‘first women’ theology — all of which further solidified my way into feminist theory.

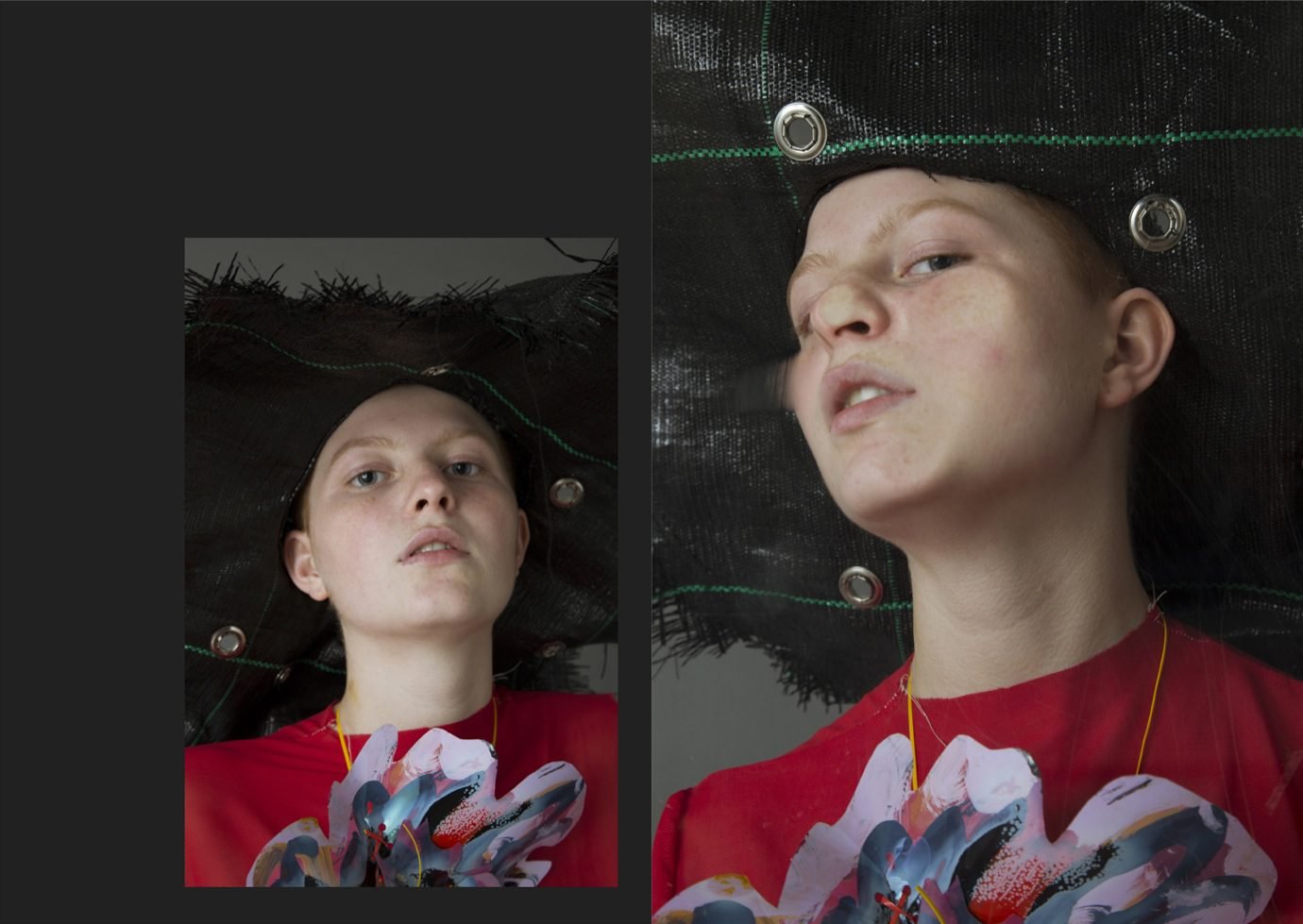

Your later works move into performance and video, how impactful was starting your masters in this progression?

The move from the US to the UK made one thing very clear: objects weigh a lot and take up space. I’d already been wanting to try out performance, but was always a little frightened by it. After the masters finished, my wife and I knew we’d be forced to move back to America soon. As my studio was now in our bedroom, I thought making more ‘objects’ seemed unwise — it just felt like the right time to bite the bullet and dive headfirst into film and performance. It was certainly a practical decision, but ultimately it had a profound impact on my practice and offered a sense of unrestricted freedom I hadn’t felt before.