In her final year of the BA Fine Art course at CSM, the Leicestershire-born student is in the process of planning her final project for the degree show in May 2016. “I’ve always felt like my work doesn’t really fit in the studio, because the studio is so white and it’s a gallery space, rather than somewhere like here where people are socialising,” she explains, looking up to the gently lit exposed beams of the ceiling in Caravan, Granary Square. With an interest in art writing, Green, 21, worries that her tutors will have reservations about her engagement in the course when looking to her previous work. The art is, “quite a personal thing for me, and I don’t really know how much personal work is on the spectrum of being marked.” But subjectivity and being marked are just part of the game when you’re a student at one of the best art schools in the world.

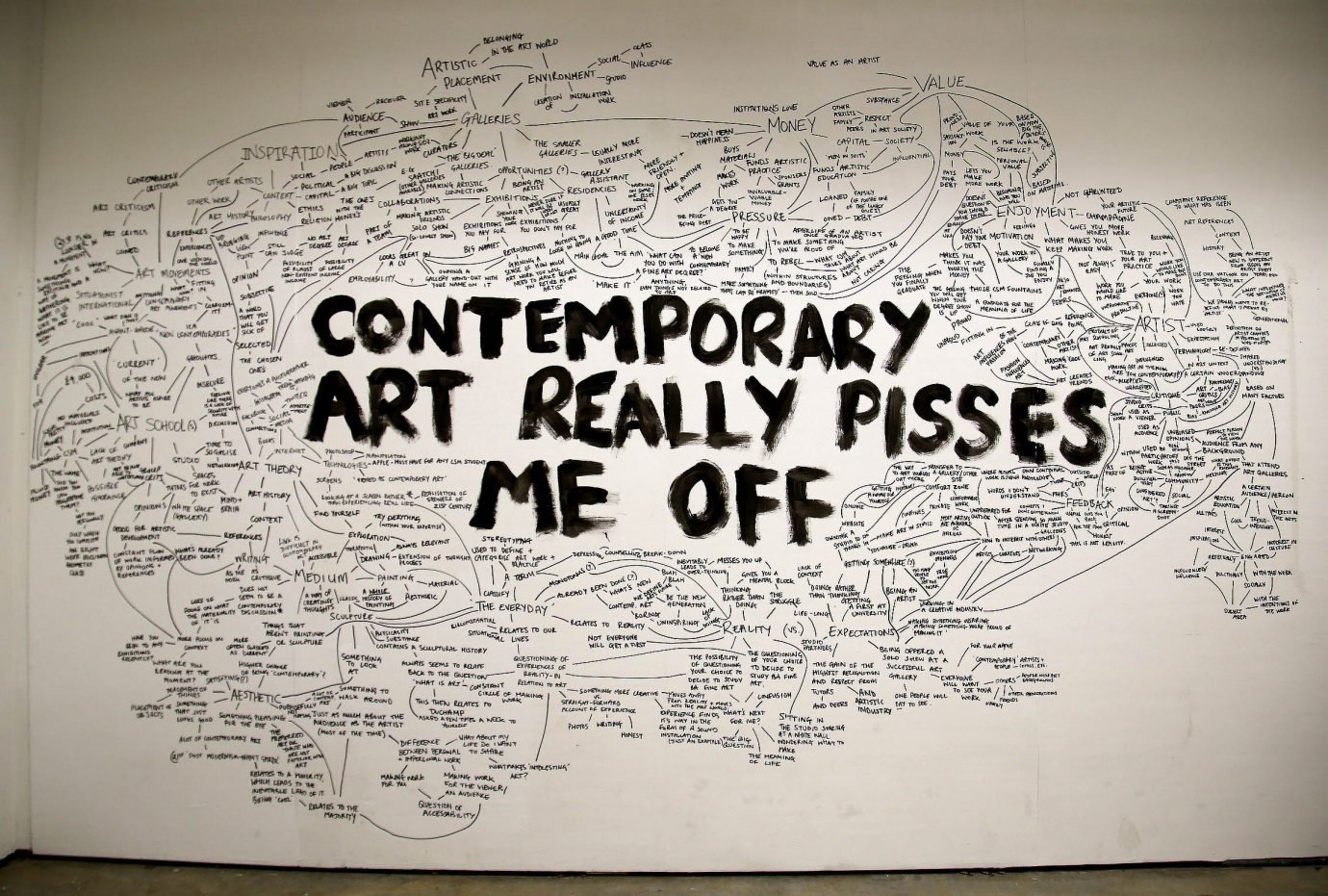

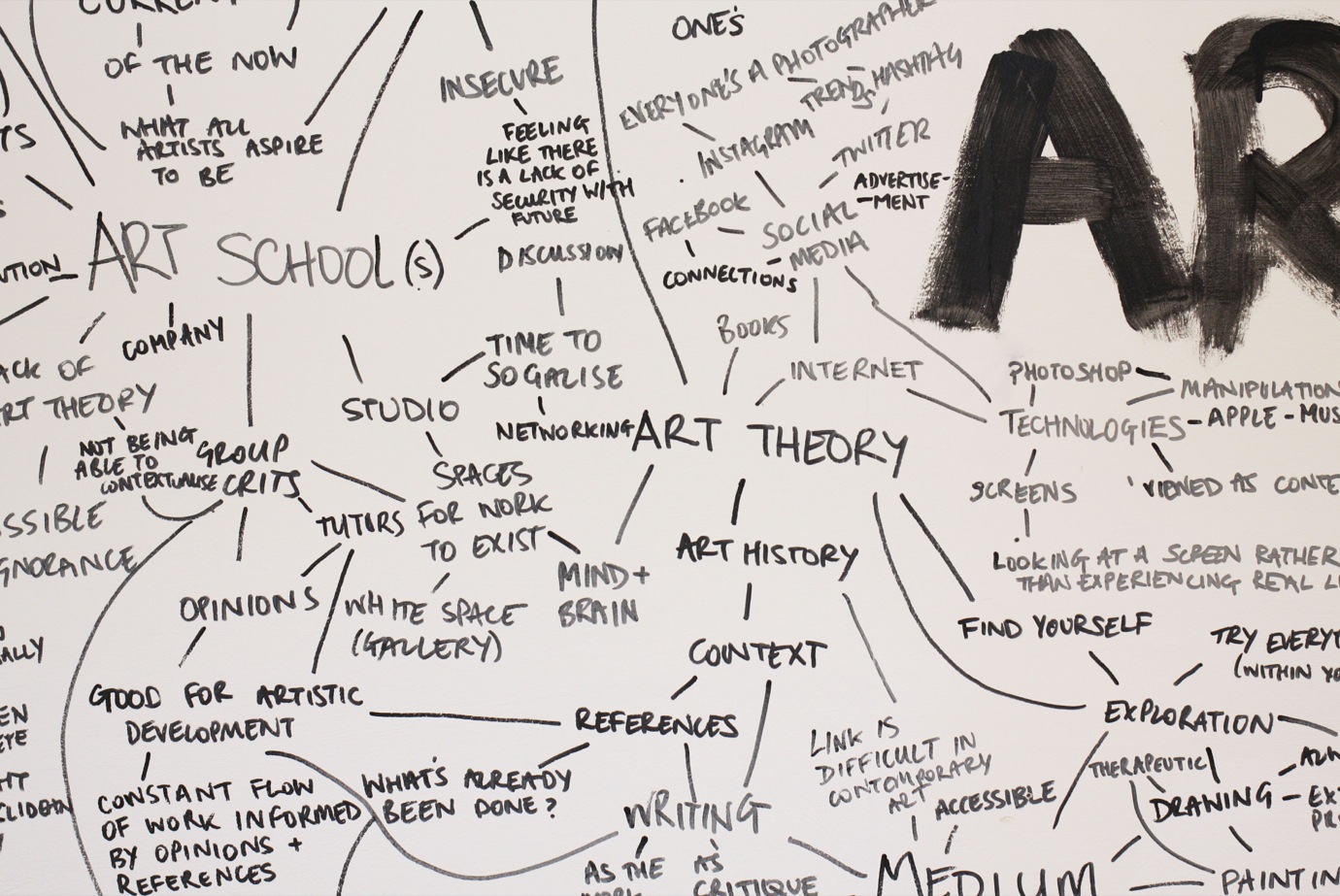

Sipping her espresso, Celia Green seems conflicted; has she made the right decision by choosing Central Saint Martins? In her piece, ‘Contemporary Art Really Pisses Me Off’, a large mind-map that she has crafted on the wall with paint and felt pen, she explains all the things that annoy her about the world to which she has dedicated her life to date. In a segment devoted to technology, she laments the sheer predictability of contemporary art, including CSM fine art students’ obsession with Apple and Instagram – and the fact that ‘everyone’s a photographer.’

“THE BIG MIND-MAP CAN’T REALLY BE SOLD, BECAUSE IT’S PAINTED IN MY STUDIO ON THE WALL.”

From the town of Melton Mowbray, which is known as being the home of the pork pie, Green was always attracted by the prospect of coming to the big smoke. “Even if I ended up not liking the course, at least I would have been in London,” she admits, crediting the city for being an art hub, with an abundance of galleries that, “you don’t get anywhere else.” It is with a list of galleries to visit after finishing this interview that Green defends not going back to Melton Mowbray often enough. Having lived in London for two years, and contrary to the great expectations she had of the city, there’s one way in which it falls short; “I expected London to be a bit more social, I imagined people talking to each other more. I know that sounds obvious, but everyone just lives their own lives here.” She makes the comparison to Melton: a small, friendly town of 25,000 where “everyone knows everyone.”

The mind-map expresses Green’s anxiety that she is, ‘unprepared for outside’ because of, ‘spending so much time in a white studio.’ She tells me about her semester at The Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, comparing it to CSM and celebrating how its small size encouraged students from many different artistic fields to mix and mingle, rather than remain in their respective white studios. “It wasn’t like here, where it’s almost like separate parts of the building for separate people that not everyone can get into.” We both look down to the table at my student card-cum-access key.

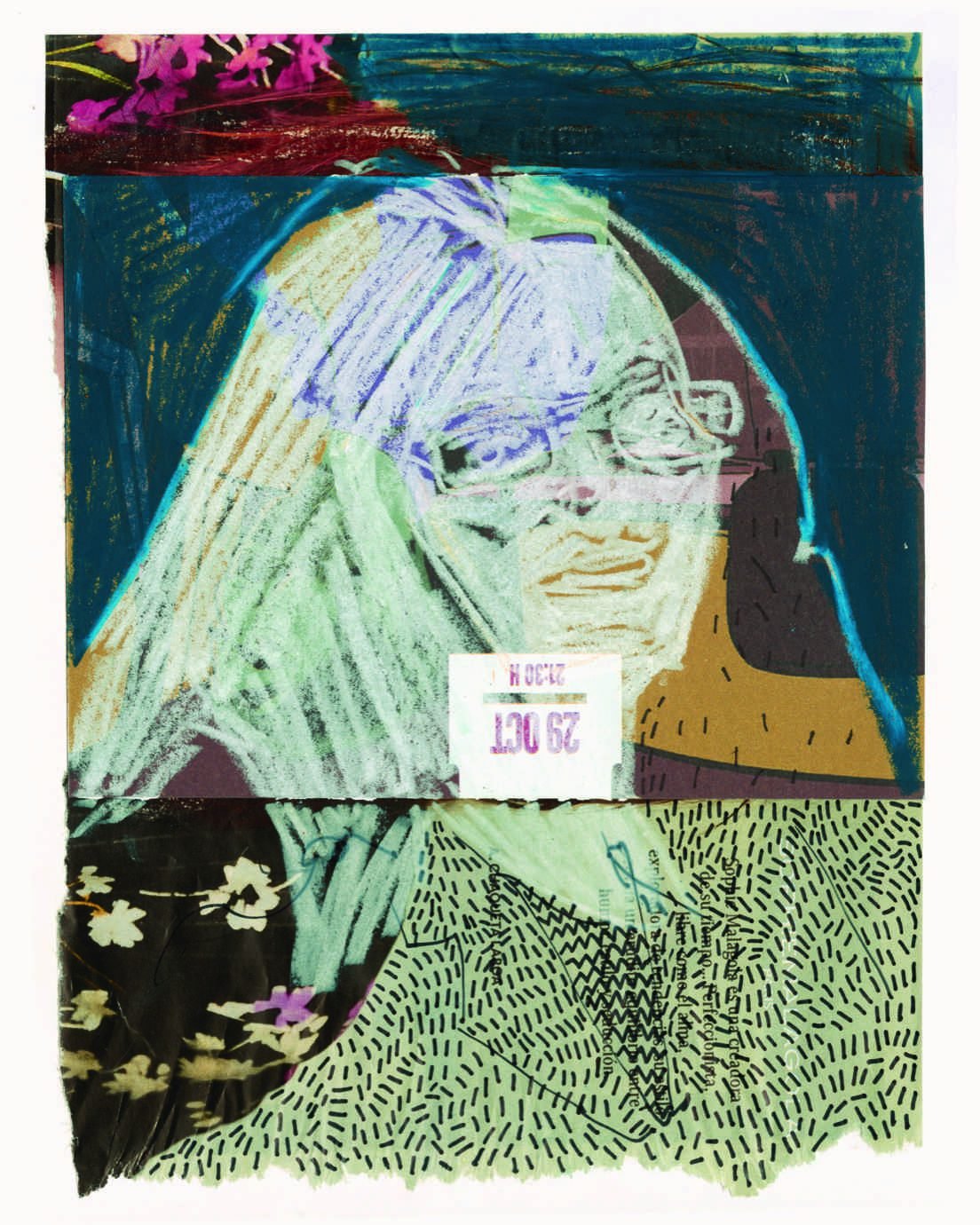

Words and interaction play a huge role in Green’s work; unlikely, perhaps, in the discipline of fine art, which you might imagine to be solely focussed on aesthetics. “For my portfolio, I didn’t put a single photo in there, it was just writing…it was the only way to present my work, whether they’ll like it or not.” Another of Green’s works, ‘Word to a pigeon’, is a poem she wrote about a pigeon flying into her head when cycling into university. The poem was made into a performance of spoken word where she interacted with the audience. It’s not just a case of going against the grain; Green’s work is a manifestation of herself and her experiences: “I want to make work about how I’m feeling.” In her mind-map, she explains that the difference between personal and impersonal work is that the latter is ‘making work for the viewer/an audience.’ She gives the example of art that corporate companies commission, “in someone’s nice fancy building that they want filled with something inspirational for their employees.” For Green, it’s the opposite. To her, it’s personal.

What ‘Contemporary Art Really Pisses Me Off’ and ‘Word to a pigeon’ have in common, is that they cannot be commercialised. “The big mind-map can’t really be sold, because it’s painted in my studio on the wall,” she explains. It’s the same with ‘Word to a pigeon’: the beauty is within its spontaneity. Green dislikes commercial art, which she defines as being something made with the intention of being sold. With that money-making disdain in mind, Green will be giving the two allocated guest passes for the degree show not to gallerists or buyers, but to her parents, something that is not encouraged as, “there are more important people that you can invite.” As the first of her siblings to graduate, it is going to be a landmark day for Green’s parents. It will mean the world for them to be invited, which, to Green, is art in itself and is perfect stimulus for the art she strives to create. Or write.