Can you tell me a bit about your upbringing and how that affected you as an artist?

I grew up in North London and went to a kind of a hippie school from the age of 4 to 17. It was very artsy, and that really shaped my trajectory and life. My mom was always interested in art, so we went to museums a lot when I was a kid; we visited France and looked at the churches and art there too. She was also a bit of a painter and I used to go to these classes in Hampstead with her at night and paint. So I grew up with a lot of art around. I was always drawing at home, cutting pictures out of magazines and making a big pin board in my room. And I got a little Brownie camera, and was taking snaps. I started doing portraits of people. Going to the beach, I would be sitting there with my uncle and drawing him. I was just really into it. No parent wants their kid to be an artist; it’s not the greatest way to make a living, but there really was no stopping me. So in the end, I ended up at Saint Martins. It was just an exciting time because it was very experimental. It was a foundation course that I did there, but it really shaped me. Basically you’re at college doing anything you want. I made a bunch of friends immediately. It was also very political at the time and we were all into leftie magazines. There was about eight of us and we would go to Patisserie Valerie on Old Compton Street every morning to talk about politics, art, plotting the downfall of Western society or whatever we were doing at the time. But we were also drawing the whole time. I lived in this semi-squat in Streatham. My rent was £5 a week and it was full of other students, so we used to do what students do: sit around drawing each other, go to jumble sales and smoke pot. It was definitely a hybrid art environment. The foundation course itself was very free form – you had to attend classes, but it was more about being in the environment. We were all hyper into our art, doing little performance pieces on the street, those crazy things. At that time David Hockney was really big and I thought I wanted to be a portrait artist like Hockney, but I never thought my drawings were quite good enough. So after Saint Martins I decided to go and study photography at the London College of Printing, which is now the LLC.

I think it’s interesting, though, because if you look at painting versus photography, there are some parallels in terms of composition, use of colour, things like that. So those skills did transfer.

Totally, it’s about looking and documenting. When I do portraits now, it’s all about the relationship and I think that’s the same. I still go to the odd life drawing class to keep up. It wasn’t like the drawings I was doing were imaginative or conceptual. I just liked to sit and draw somebody and that morphed into taking portraits.

There’s this very stripped back aesthetic to August Sander’s work and it’s an interesting contrast to what we have nowadays. There are still a few photographers that keep it in that natural environment as so much of it is Photoshopped, with colour filters or the backgrounds added in.

I shoot digital now, but I don’t do that much to my pictures. I tweak the contrast a little bit, but I don’t approve of that [excessive digital alteration]. I grew up shooting film, where every shot has a dollar value to it. You had to be a lot more careful and I still work that way now. I don’t shoot hundreds and hundreds of shots. It’s not that hard, you just have to stop and think for a minute. I’ve been lucky, because I do portraits, I have someone’s attention, be it for five minutes or two hours, and we can figure stuff out. I think it’s important to compose and get it right the first time. Photoshop is an incredible tool, but it’s pretty horrendous the way they make everyone look like they are 20 years old. It’s really strange – in 100 years, when people look back they’ll say everybody just looked like Barbie dolls. I understand people want to look young and beautiful, but old and beautiful is great as well.

With punk and hip hop being more male-dominated fields back then, how was it for you getting into those scenes and photographing them?

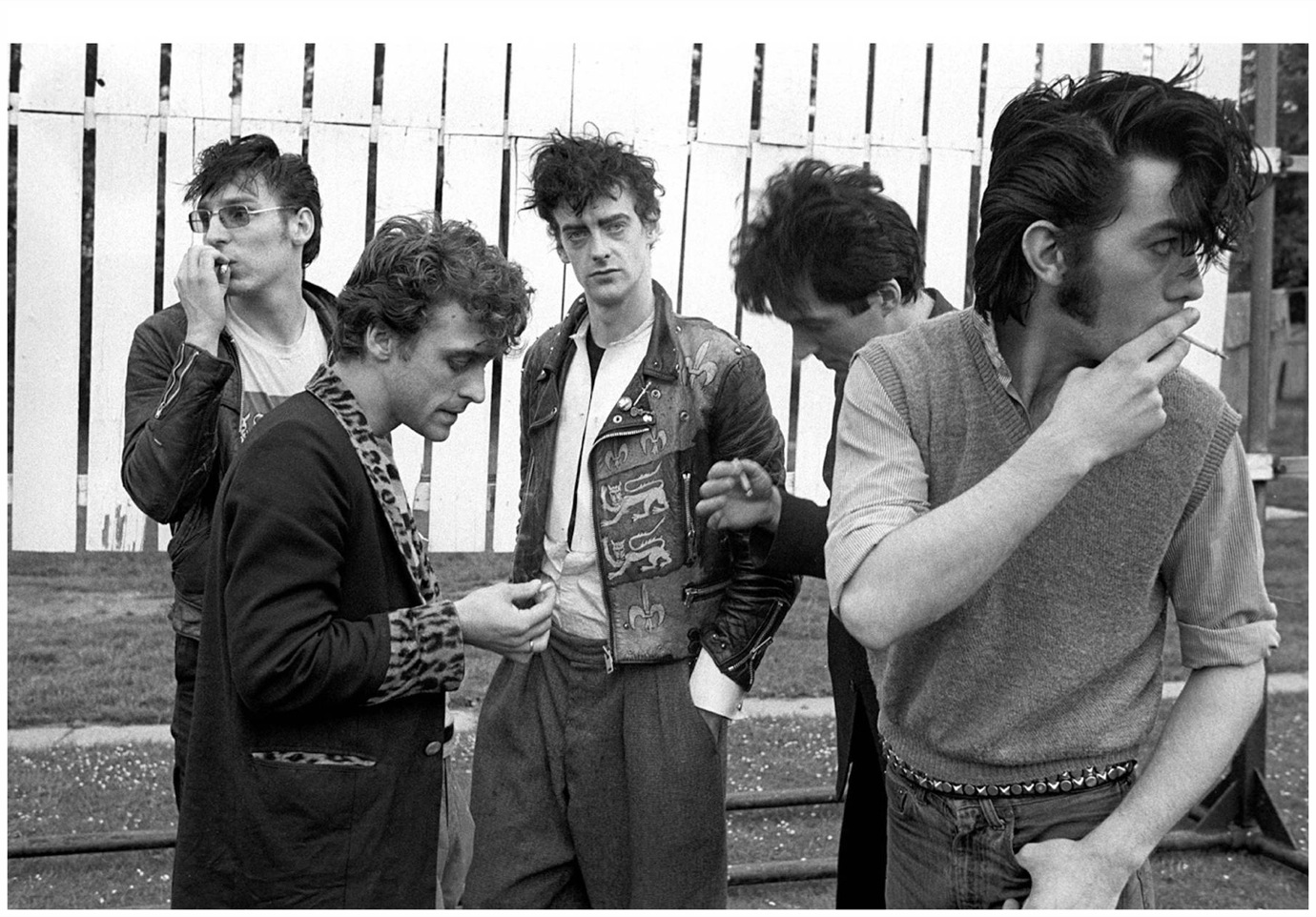

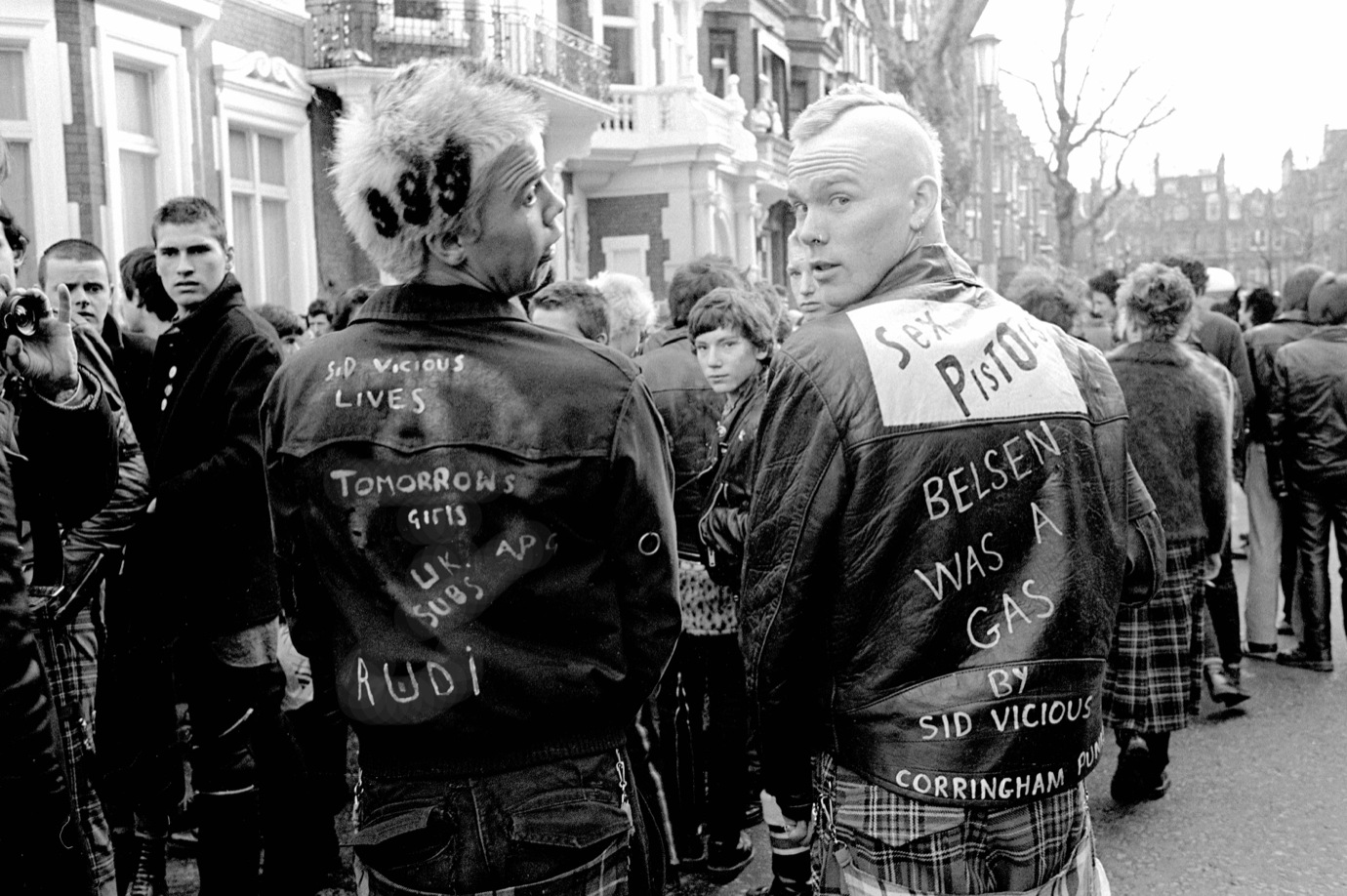

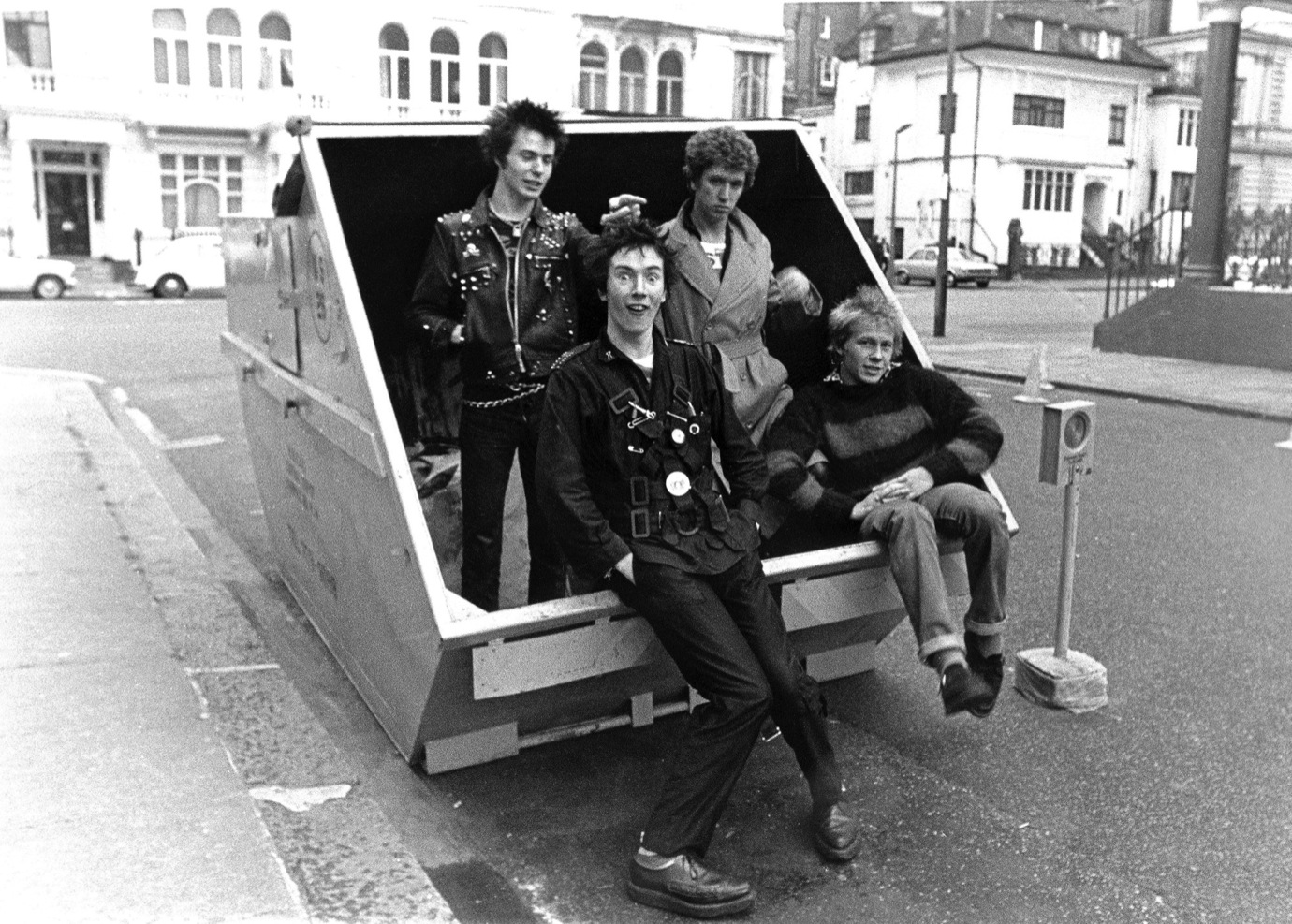

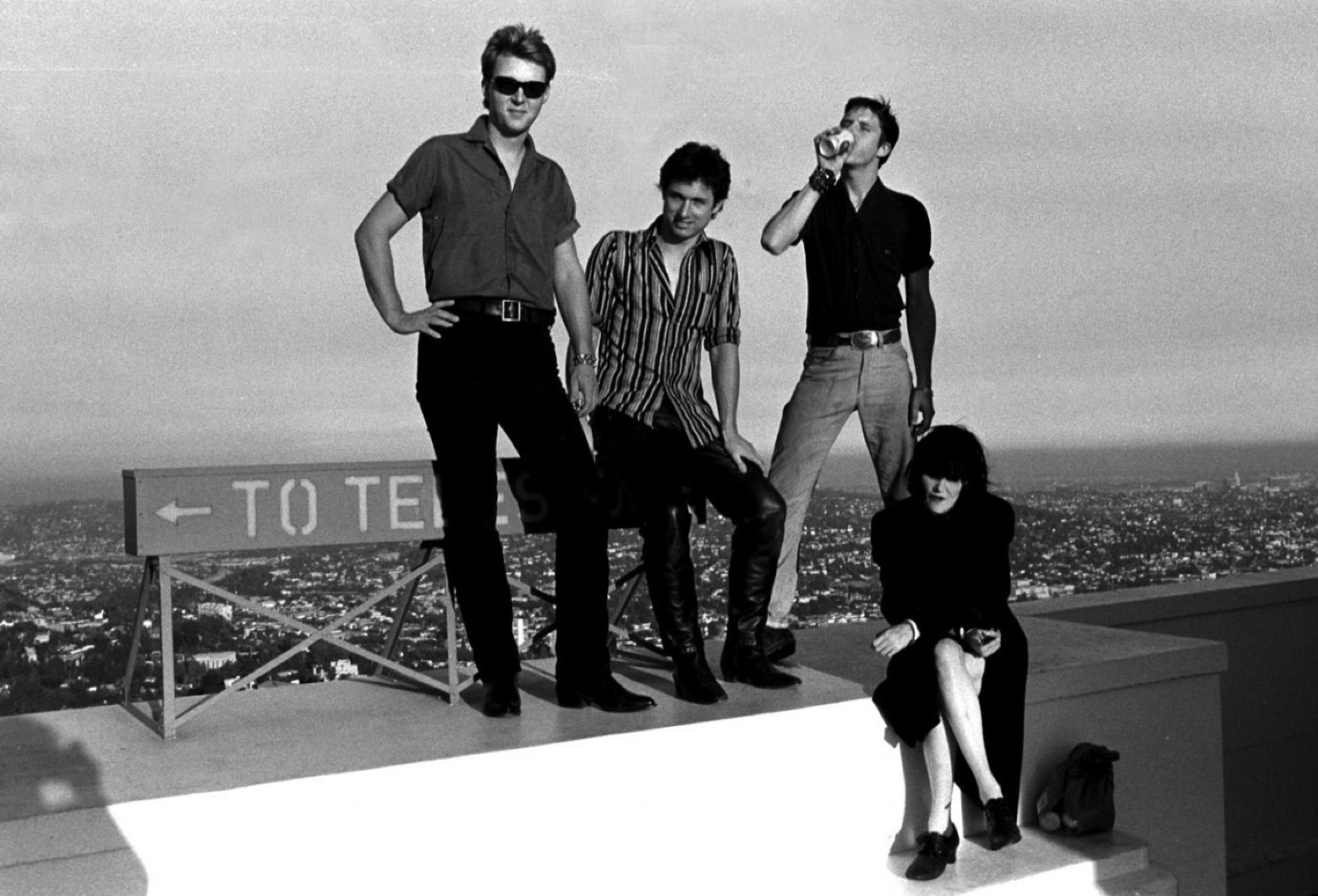

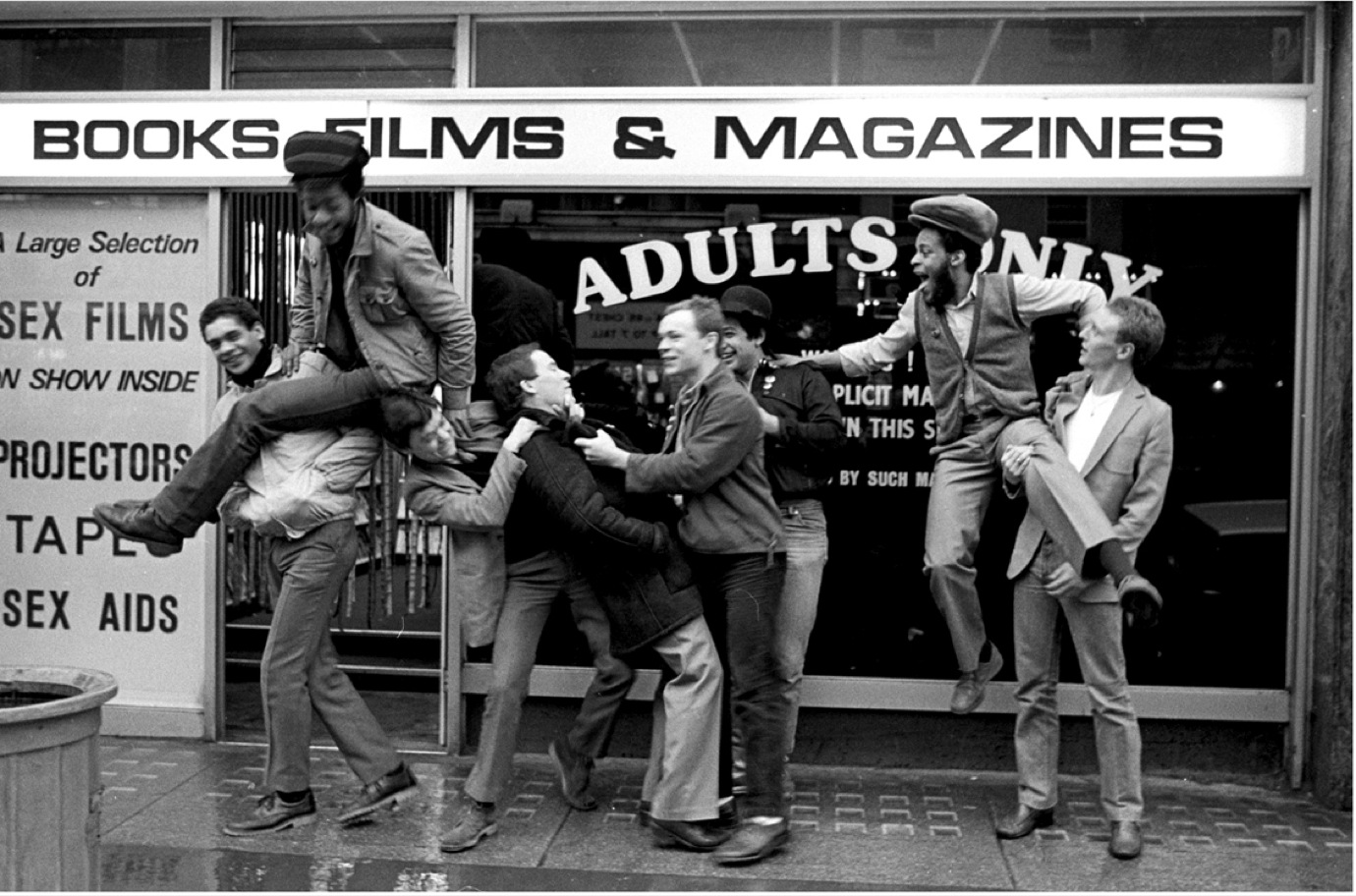

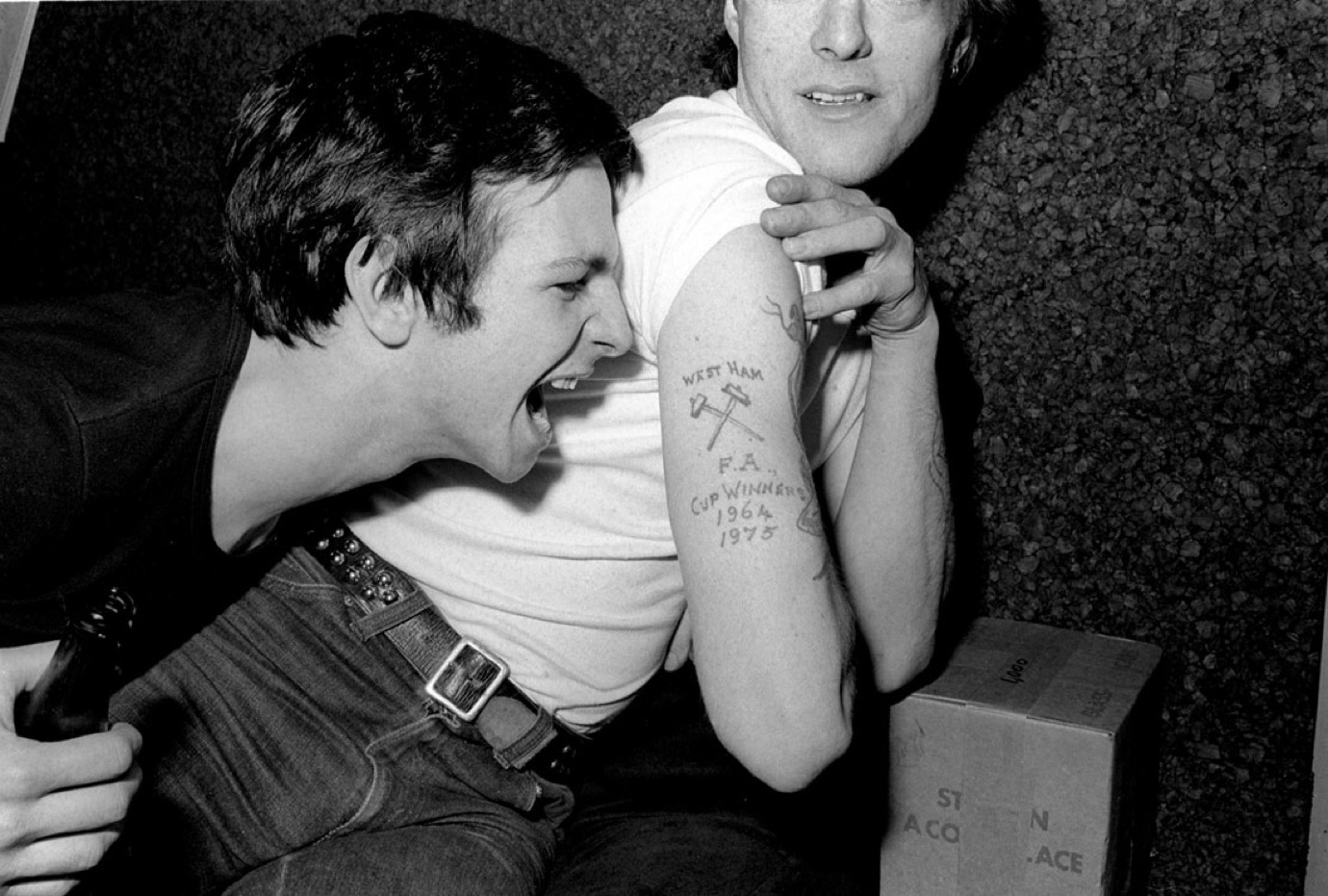

When I started at Melody Maker, there was only one other woman working there. It was all guys and they’re more or less rocker types that went down to the pub and got drunk. I was an art student, wearing white Levi’s and a Madness T-shirt. I felt more like I didn’t fit in because I was so artsy and they would make comments about my style, with me being there dressed in my pyjamas and sneakers. I thought I looked cool and they were like, what’s wrong with you? But all the bands were cool with it because a lot of the punk bands were former art students. I never felt discriminated against particularly as a woman. <i>Melody Maker was more of a rock magazine and because I was into punk, mods and all the new genres, when those assignments came up they were just like, “Oh chuck them to her.” That was fine by me, I got to photograph Boy George, the Sex Pistols, I got all of that stuff. When I came to New York in 1982, it really worked to my advantage that I was a woman. I’d go up to the Bronx to take a photograph of Afrika Bambaataa, he was expecting some American male photographer and I’d turn up. I was like a stranger walking around in their land and because I was a woman I was less threatening. I was photographing a lot of African American culture and because I wasn’t from here, I got what they call a “hood pass”. I was very curious about them and they were curious about me. It was exactly the same when I went to photograph this East L.A. gang. They’re like, “You’re not American, what are you doing here?” I brought a box of my punk and mod photographs. I would say, “These are the gangs in England, I want to photograph you and take these pictures back to the people in Europe.” They got that concept. People were always really nice to me and respectful. Even some of the rap artists that were so-called dangerous or scary, I never had any problems with whatsoever. I think they didn’t look at me with the same expectations they would have had if I was American.

THEY ASKED ME IF I REMEMBERED WHAT COLOUR THE CAR IN THE PHOTOGRAPH WAS. IF IT WAS BLUE, IT WAS 1982, AND IF IT WAS GOLD IT WAS 1983, BECAUSE SOMEBODY WAS SHOT IN THIS CAR, THE CAR WAS COVERED IN BLOOD AND THEY HAD TO REPAINT IT.”

I worked a lot with Salt-N-Pepa. The first time that I shot them was for a British magazine and they hadn’t even put out a record. I don’t know how this magazine had heard of them. I was living over on Avenue B and had them come over. It was a hot summer’s day like this and we took a walk in the neighbourhood. They were just giggly girls and we were just hanging out and having fun. I was taking pictures of them in front of various murals and little stores, this that and the other. We got along really well and that led to a long relationship. I did a lot of album covers for them, it was always super chill. They had their own style: jackets made by this guy Dapper Dan in Harlem, earrings and gold chains.

Yeah, it was very DIY and just small communities back then.

Totally, just turn up and take pictures. This guy Just-Ice, I was working for his record label, Sleeping Bag Records, and they told me they wanted me to do the album cover for him. He was this big guy, completely scary. I was like, whatever. So he comes over, a nice guy, very polite, we do all the shots and end up going to drink Long Island Iced Teas in the bar across the street. I remember he had these gold caps and had to take them out and put them in his pocket because we were eating taco chips and he didn’t want the chips to get on his gold teeth. This is supposed to be this guy who possibly might have murdered somebody, but obviously it turned out he hadn’t. A few days later somebody is ringing at the studio door and it’s him. He’s got this box and inside is this little tiny kitten he’s just adopted. He said, “I got this little kitten and wanted to show you. I’m going to call him Money Clip.” There were a lot of stories like that. Things that were supposed to be frightening were not really frightening to me. I mean, these L.A. gang girls, they apparently used to go to school with razor blades in their mouth because there’s so much violence there and they could just whip out these razor blades and cut people up. I’m just sitting there listening to these stories and taking pictures of them.

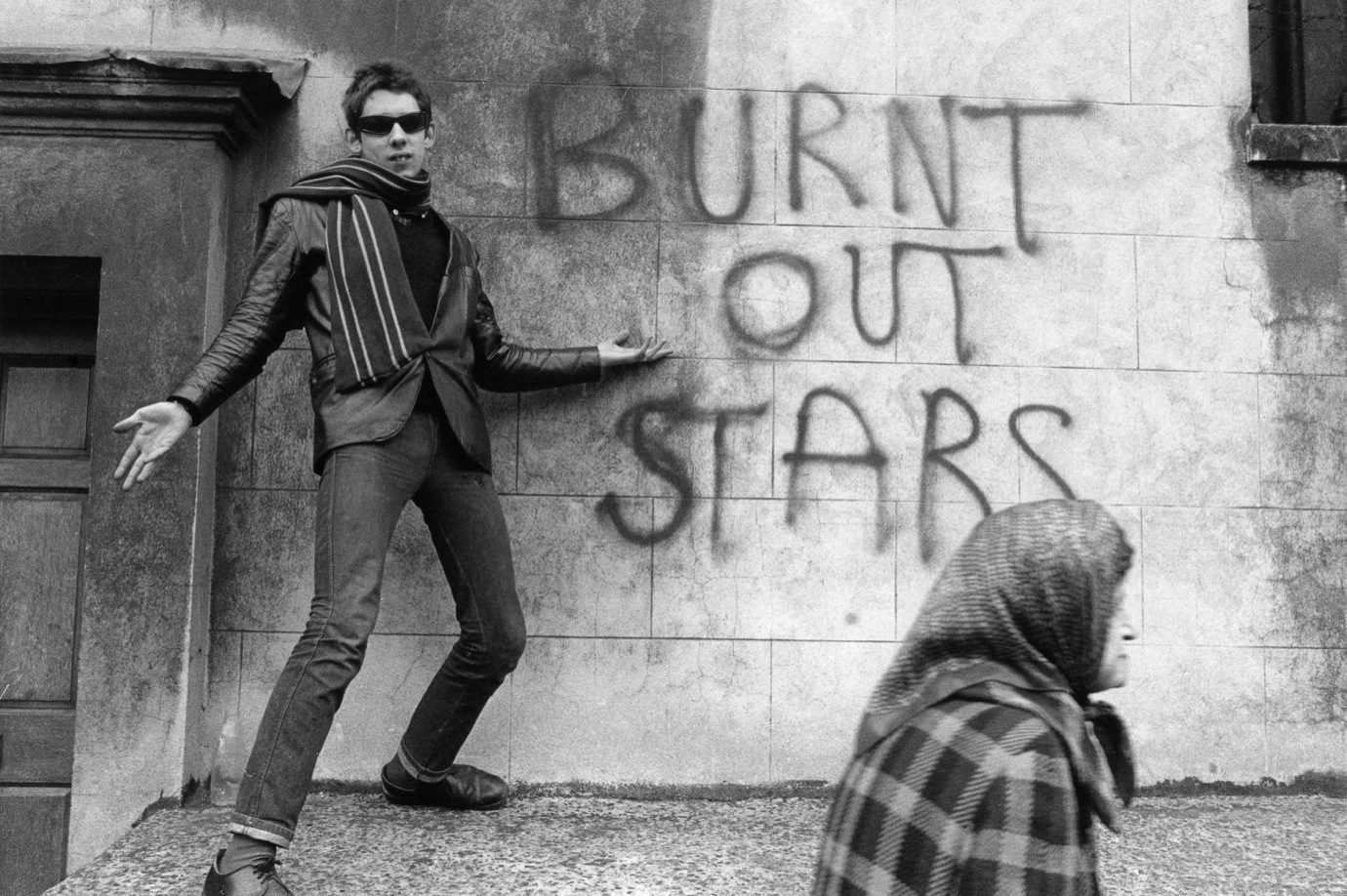

Run DMC, Public Enemy, NWA – what sounds like a top trio of hip hop’s finest is actually just the beginning of the roster of famous names that Janette Beckman has photographed. Not limiting herself to one music genre – she started off photographing punk bands like the Sex Pistols and The Clash for publications such as The Face and Melody Maker – Beckman has an eye for capturing musicians and influencers of the moment in their element. The Londoner’s extensive portfolio of work also includes the documentation of various subcultures, from east L.A.’s El Hoyo Maravilla gang to Teds proudly presenting their Elvis Presley records on the streets of London.

Meeting Beckman at her Lower East Side studio on a hot summer’s day, it’s easy to see how she manages to capture her subjects in such a natural and laid-back manner. With her wildly curled raven-coloured locks, friendly smile and relaxed attitude, the photographer immediately makes one feel comfortable in her presence. Slouched back in a chair, her two cats freely prancing around the open loft space, she recounts each experience with the same enthusiasm and excitement as if it had just happened yesterday. Nowadays she may be photographing her subjects on a Fuji XT1 digital camera instead of her trusted Hasselblad, but her images have the same subversive edge as ever. Flipping through her four published volumes of work, Rap, Portraits & Lyrics of a Generation of Black Rockers, Made In The UK: The Music of Attitude 1977-1983, The Breaks, Stylin’ and Profilin’ 1982-1990 and El Hoyo Maravilla, Beckman contemplates her earliest artistic influences, the changing face of photography, and creativity on both sides of the pond.

“No parent wants their kid to be an artist; it’s not the greatest way to make a living, but there really was no stopping me.”

Can you tell me a bit about your upbringing and how that affected you as an artist?

I grew up in North London and went to a kind of a hippie school from the age of 4 to 17. It was very artsy, and that really shaped my trajectory and life. My mom was always interested in art, so we went to museums a lot when I was a kid; we visited France and looked at the churches and art there too. She was also a bit of a painter and I used to go to these classes in Hampstead with her at night and paint. So I grew up with a lot of art around. I was always drawing at home, cutting pictures out of magazines and making a big pin board in my room. And I got a little Brownie camera, and was taking snaps. I started doing portraits of people. Going to the beach, I would be sitting there with my uncle and drawing him. I was just really into it. No parent wants their kid to be an artist; it’s not the greatest way to make a living, but there really was no stopping me. So in the end, I ended up at Saint Martins. It was just an exciting time because it was very experimental. It was a foundation course that I did there, but it really shaped me. Basically you’re at college doing anything you want. I made a bunch of friends immediately. It was also very political at the time and we were all into leftie magazines. There was about eight of us and we would go to Patisserie Valerie on Old Compton Street every morning to talk about politics, art, plotting the downfall of Western society or whatever we were doing at the time. But we were also drawing the whole time. I lived in this semi-squat in Streatham. My rent was £5 a week and it was full of other students, so we used to do what students do: sit around drawing each other, go to jumble sales and smoke pot. It was definitely a hybrid art environment. The foundation course itself was very free form – you had to attend classes, but it was more about being in the environment. We were all hyper into our art, doing little performance pieces on the street, those crazy things. At that time David Hockney was really big and I thought I wanted to be a portrait artist like Hockney, but I never thought my drawings were quite good enough. So after Saint Martins I decided to go and study photography at the London College of Printing, which is now the LLC.

I think it’s interesting, though, because if you look at painting versus photography, there are some parallels in terms of composition, use of colour, things like that. So those skills did transfer.

Totally, it’s about looking and documenting. When I do portraits now, it’s all about the relationship and I think that’s the same. I still go to the odd life drawing class to keep up. It wasn’t like the drawings I was doing were imaginative or conceptual. I just liked to sit and draw somebody and that morphed into taking portraits.

“Photoshop is an incredible tool, but it’s pretty horrendous the way they make everyone look like they are 20 years old. It’s really strange – in 100 years, when people look back they’ll say everybody just looked like Barbie dolls.”

Your work is a documentation of the time, but then obviously has an artistic value as well. How do those two things come together for you?

I love to take portraits in the street and I’m always aware of the surroundings, what’s going on in the street, in the background. It makes a timeline. I took a picture of Futura and Dondi, two really famous graffiti artists, and an English dumpster which they tagged; this makes a whole story. I would always find walls that had things on them. It was a document of the times because that stuff isn’t there anymore. As much as I love my studio pictures, this [gang] project I did is a prime example. I took this picture of three girls who were part of this East L.A. gang called the Hoyo Maravilla. I spent the whole summer going there and shooting them. I recently reconnected with them a couple of years ago. They’re all fully grown women now: one of them works for the D.A.’s office, one works in rehabilitation for gang members and the other drives a Mercedes and has a big office job. We timelined the photo as I thought it was taken in 1982. They asked me if I remembered what colour the car in the photograph was. If it was blue, it was 1982, and if it was gold it was 1983, because somebody was shot in this car, the car was covered in blood and they had to repaint it. So you know, things like this can really make a timeline, and obviously clothing, style, the way the kids are, their attitude. It gives a lot of flavour. Here’s a picture of Run DMC, on the street they grew up on in Hollis, Queens, in 1984. I had never been to Hollis and got this assignment. I just had a phone number and met someone at a subway, I wasn’t expecting this tree-lined street. I grew up going to the National Portrait Gallery a lot and looking at paintings done by artists in the 17th and 18th centuries. Those were the things that influenced me, portraits of life in those days. And I guess I somehow try and make portraits of what life is like today.

Was there a specific photographer that inspired you?

I got this August Sander book out of the library when I was in college and loved it so much, I never brought it back. He photographed working people, where they worked, on the street. They are simple photographs and not posed, people are just looking in the camera, [it’s] very natural. Irving Penn’s portraits; Avedon; Cartier-Bresson; William Klein – they mostly photographed people in environments, too. Even now, I’m the New York editor of Jocks&Nerds magazine, and we do a lot of portraits. I try to put people where they live. I get an assignment to photograph somebody and they’re like, “Oh, should I come around to see you,” and I say, “No, that’s okay, I’ll just come around to where you are – on the street where you live, in the living room, around the corner in front of a deli.” Signage, cars going by, taxis… all of that stuff means a lot to me, getting that flavour of the city.

“We would go to Patisserie Valerie on Old Compton Street every morning to talk about politics, art, plotting the downfall of Western society or whatever we were doing at the time.”

There’s this very stripped back aesthetic to August Sander’s work and it’s an interesting contrast to what we have nowadays. There are still a few photographers that keep it in that natural environment as so much of it is Photoshopped, with colour filters or the backgrounds added in.

I shoot digital now, but I don’t do that much to my pictures. I tweak the contrast a little bit, but I don’t approve of that [excessive digital alteration]. I grew up shooting film, where every shot has a dollar value to it. You had to be a lot more careful and I still work that way now. I don’t shoot hundreds and hundreds of shots. It’s not that hard, you just have to stop and think for a minute. I’ve been lucky, because I do portraits, I have someone’s attention, be it for five minutes or two hours, and we can figure stuff out. I think it’s important to compose and get it right the first time. Photoshop is an incredible tool, but it’s pretty horrendous the way they make everyone look like they are 20 years old. It’s really strange – in 100 years, when people look back they’ll say everybody just looked like Barbie dolls. I understand people want to look young and beautiful, but old and beautiful is great as well.

With punk and hip hop being more male-dominated fields back then, how was it for you getting into those scenes and photographing them?

When I started at Melody Maker, there was only one other woman working there. It was all guys and they’re more or less rocker types that went down to the pub and got drunk. I was an art student, wearing white Levi’s and a Madness T-shirt. I felt more like I didn’t fit in because I was so artsy and they would make comments about my style, with me being there dressed in my pyjamas and sneakers. I thought I looked cool and they were like, what’s wrong with you? But all the bands were cool with it because a lot of the punk bands were former art students. I never felt discriminated against particularly as a woman. Melody Maker was more of a rock magazine and because I was into punk, mods and all the new genres, when those assignments came up they were just like, “Oh chuck them to her.” That was fine by me, I got to photograph Boy George, the Sex Pistols, I got all of that stuff. When I came to New York in 1982, it really worked to my advantage that I was a woman. I’d go up to the Bronx to take a photograph of Afrika Bambaataa, he was expecting some American male photographer and I’d turn up. I was like a stranger walking around in their land and because I was a woman I was less threatening. I was photographing a lot of African American culture and because I wasn’t from here, I got what they call a “hood pass”. I was very curious about them and they were curious about me. It was exactly the same when I went to photograph this East L.A. gang. They’re like, “You’re not American, what are you doing here?” I brought a box of my punk and mod photographs. I would say, “These are the gangs in England, I want to photograph you and take these pictures back to the people in Europe.” They got that concept. People were always really nice to me and respectful. Even some of the rap artists that were so-called dangerous or scary, I never had any problems with whatsoever. I think they didn’t look at me with the same expectations they would have had if I was American.

“They asked me if I remembered what colour the car in the photograph was. If it was blue, it was 1982, and if it was gold it was 1983, because somebody was shot in this car, the car was covered in blood and they had to repaint it.”

What were the most memorable moments and people you encountered?

I worked a lot with Salt-N-Pepa. The first time that I shot them was for a British magazine and they hadn’t even put out a record. I don’t know how this magazine had heard of them. I was living over on Avenue B and had them come over. It was a hot summer’s day like this and we took a walk in the neighbourhood. They were just giggly girls and we were just hanging out and having fun. I was taking pictures of them in front of various murals and little stores, this that and the other. We got along really well and that led to a long relationship. I did a lot of album covers for them, it was always super chill. They had their own style: jackets made by this guy Dapper Dan in Harlem, earrings and gold chains.

Yeah, it was very DIY and just small communities back then.

Totally, just turn up and take pictures. This guy Just-Ice, I was working for his record label, Sleeping Bag Records, and they told me they wanted me to do the album cover for him. He was this big guy, completely scary. I was like, whatever. So he comes over, a nice guy, very polite, we do all the shots and end up going to drink Long Island Iced Teas in the bar across the street. I remember he had these gold caps and had to take them out and put them in his pocket because we were eating taco chips and he didn’t want the chips to get on his gold teeth. This is supposed to be this guy who possibly might have murdered somebody, but obviously it turned out he hadn’t. A few days later somebody is ringing at the studio door and it’s him. He’s got this box and inside is this little tiny kitten he’s just adopted. He said, “I got this little kitten and wanted to show you. I’m going to call him Money Clip.” There were a lot of stories like that. Things that were supposed to be frightening were not really frightening to me. I mean, these L.A. gang girls, they apparently used to go to school with razor blades in their mouth because there’s so much violence there and they could just whip out these razor blades and cut people up. I’m just sitting there listening to these stories and taking pictures of them.