What fascinates you in the reproduction of the human body?

What fascinates me is the relationship between the image we all have of body, and how impossible it is to reproduce the reality of human body, through photography, or 3D scanning, or casting, or any other way or “copying” reality, like a mirror, for example. The “mirror stage” theory developed by psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan is one of the genesis of my practice. Lacan says that we start building our identity from the moment we recognize our body in the reflection of a mirror, which is between 6 and 18 month old. From that stage, the baby will be aware of his body and that he is an entire entity. Nonetheless, the image we get in a mirror is, also, an incomplete copy of reality. It is an illusion of the Real, it is just a reflection copying in two dimensions our reality that has many dimensions. That would suggest that our identity is based on an illusion, on something that is not true reality. And we carry this through all our existence. Reproducing the human body through all kinds of techniques that I use is like a way to make more accurate the image we have of ourselves, even though a true reproduction is impossible to make. What would happen if a young child would recognize himself for the first time in a 3D scan, or a photography, or a statue of himself?

The myth of the Medusa plays a continuous research point in your work. What is your continuous fascination?

Medusa is a fascinating myth for me, because it has been used as a metaphor of psychoanalysis theories as well as in theory of photography. For example, Medusa, while seeing her face for the first time, reflected into the shiny shield of Athena (who commissioned Perseus to go cut Medusa’s head), experiences the mirror stage. This is why she is always represented with a horrified face because she realizes for the first time how ugly and scary she is. On the other hand, she has the power to turn into stone every living being that looks at her in her eyes. This has been used as a metaphor for photography. When a photograph captures a scene, everything gets frozen for eternity, just like whoever looks at Medusa in the eyes becomes a statue of stone. On top of that, this myth interestingly reproduces the concept of photography. Indeed, after Perseus cuts Medusa’s head, her horrified face stays like printed in the shield, and this is why Athena is always represented with the horrified face of Medusa on her shield. This is like a photograph in a myth that appeared way before photography was invented. By the way, Medusa’s terrible power to turn people into stone remained with her image after her death, and this is a good metaphor questioning reproduction of reality. This image remaining in the shield has something a bit more magical than photography.

Finally, there is the notion of time that is similar to the act of photography. First, it takes less than a second for Medusa to freeze you to stone, just like the photographer freezes a scene by pushing the button. Second, Perseus had to cut the head of Medusa and bring it to Athena. But Medusa immediately turned herself into stone while seeing her reflection in the shield. Then how to cut the head of a statue with a sword? Perseus had to find this accurate time while Medusa was between flesh and stone. A bit before, or a bit later, it would not work. This is very similar to what the photographer experiences while capturing the right moment in time.

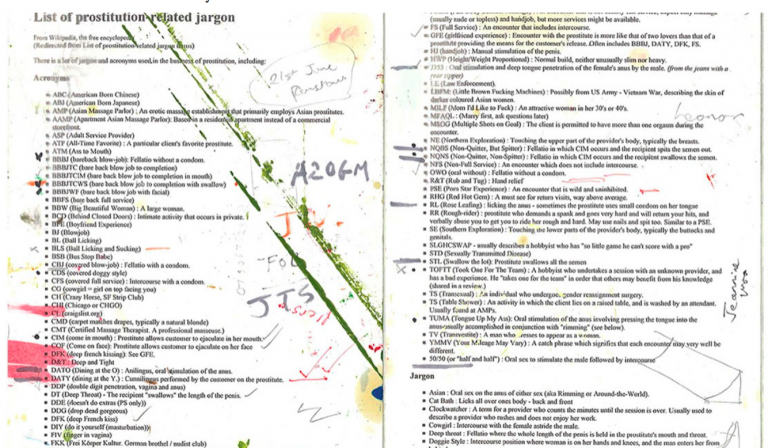

“THERE ARE BILLIONS OF NEW IMAGES CREATED EVERYDAY. WHAT DOES IT SAY ABOUT THE WORLD WE LIVE IN?”