It’s not easy getting by as an artist these days – then again, it actually never really has been. The reality is that not only recent graduates often work two jobs while producing their art, but also artists who you’d think are quite established and have solid ground underneath their feet. In the 80s, this was no different. Keith Coventry – a well-known artist as well as curator, who was endorsed early-on by Charles Saatchi in the 90s – has been no exception to this rule. Post-graduation, he’s worked as a painter and decorator for property magnate Nicholas van Hoogstraten, and (staying in the education realms) worked as a caretaker at a girls’ public school in London. We met with Keith after his show at the Pace gallery, White Black Gold, dug into his brain and work at large, and got some poignant advices for those who are at the beginning stages of their careers.

The art studio is a very special place for the artist. You spend a lot of time here and this is where, allegedly, most of your ideas should be born. How often do you come here?

Every day.

Even on the weekends?

Yeah!

And how long do you stay ?

Um, varies. But, obviously, coming up to this exhibition that I did at Pace, I was here quite early, because of the anxiety of having everything ready on time. It was quite tight. So, I was here by about 7 o’clock, and then I left around 8pm. Thirteen hours later.

Wow. So you did all of your work here, you never produce at home?

No, everything is made here.

What is your process, when you come here? What is the first thing you do?

Usually, something has been left from the night before. I come here with an idea of getting on with that first thing in the morning. So I know exactly what to do, it’s not like I walk in and wonder what needs doing. It would be one continuous work process, if it weren’t for the need of the social oppression. Having to sleep.

Do you have any rituals that you follow here?

Not really, listen to the same music… Especially when it’s coming up to the exhibition, it seems like you don’t want to be making choices about what to eat, where to eat, what to listen to. You are too busy doing the work.

Don’t you get tired of it, or uninspired?

No, no, it’s this idea that you have to drive on to the completion of the show, and so repetition becomes something important.

Do you usually know what your work will look like at the end?

I usually have an idea about what it will look like, in my mind. There are no big surprises, but it is always nice to complete the piece, realize it completely, and then enjoy it. As if there are stages to it, and, obviously the highlights. That’s where the enjoyment comes in – it’s like a slog before, and then polishing the glass, or something, looking at it… Very delayed gratification, basically.

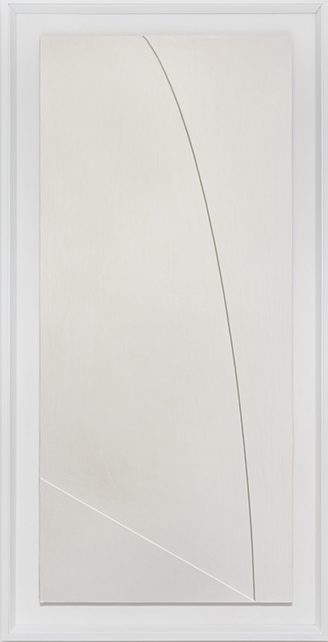

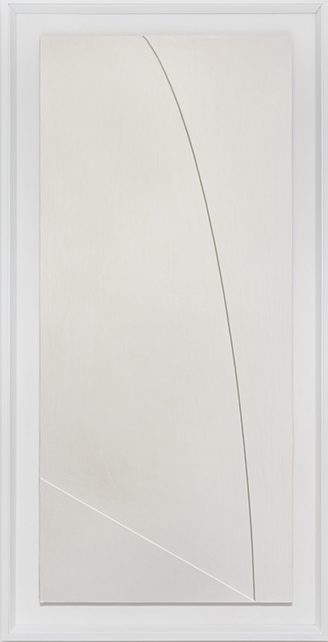

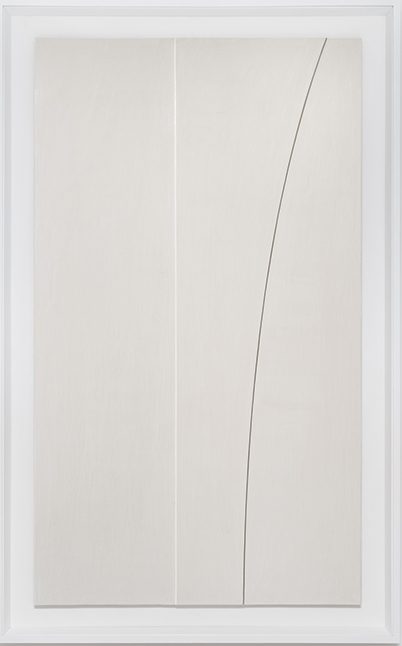

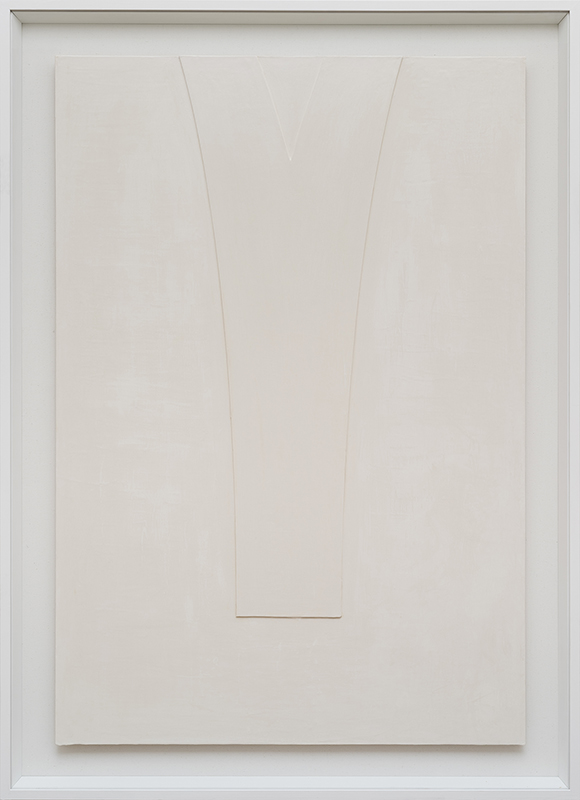

How long did it take you to create the Junk or Pure Junk pieces?

Well, it did take quite a long time, because I was moving from studio to studio. It was quite unsettling, because I was scared of damaging the works whilst moving them around in the van, since they are quite fragile. There were a few accidents… These works are quite intensive, because the material has to be mixed up. It’s rabbit skin glue with champagne chalk. It cracked, and I stripped it all the way back to the wood. The frames, and everything – they are quite heavy.

There are many stages to them, although they look very simple. It’s a little bit like a production – division of labor. There are twelve pieces, and you have to bring each piece onto the same level. When that is all completed, each piece gets moved onto the next level of production.

Junk XI (2012)

Junk VI (2012)

Junk V (2012)

Junk IV (2012)

Junk I (2012)

“I like the idea of cropping. It is infinite. You can make hundreds, possibly more, thousands of different images from one static image – if you crop it differently.”

Where would be the perfect place for Junk paintings?

There are quite a few perfect places. One would be in an amazing Roman Catholic Church in Munich. Or in a museum of modern art. Lots of places, but an idea of churches, cathedrals, museums are all sort of connected.

It’s interesting for you say that – because in their meanings, the paintings are so very much separated from religion.

I was a Roman Catholic, and I remember going to Mass, and the priest had these different colored vestments on. I think Matisse also did images of that. The simple, bold geometric shapes, they resemble that, slightly. And also the white – I don’t know what the occasion was, but sometimes the priest would wear a completely white vestment, with some kind of a shape inside it, that was almost in relief. But that’s not where they [ed. – the paintings] come from. But who knows, the subconscious takes a long time to trickle through.

I’ve heard quite often that to some people, your works remind them of works by Anselm Kiefer.

Kiefer? That’s something that I have never thought about.

The Destroyed Shop Window – the work is so terrifying, and it is so difficult to look at it…

That’s about the scale of Kiefer’s paintings. It’s just a simple image, with elements repeated in it, a bit like Kiefer’s sheaves of wheat or straw. The reference in my paintings has got to be the constructivist Russian or Dutch art.

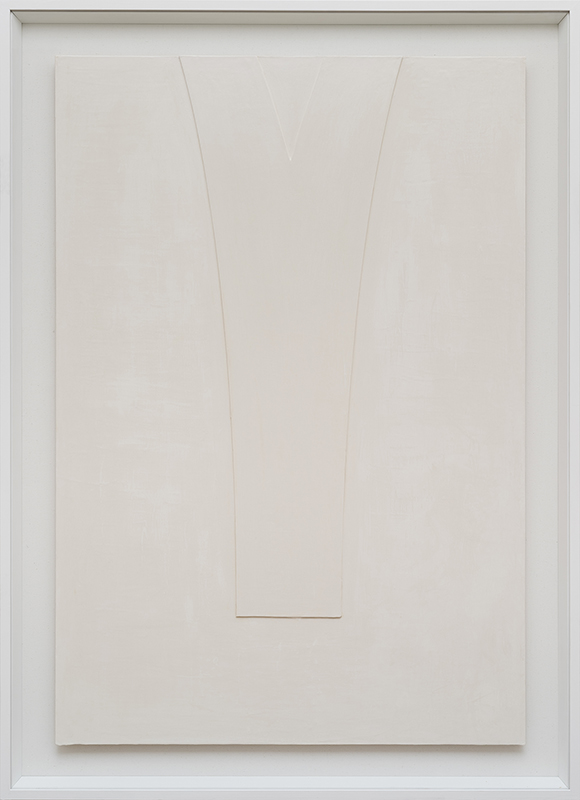

Window (2016)

Looted Shop Front (1995)

Yes, and about the window – you explained it using the idea of a grid.

The grid is something, I believe, that was created in the early 70’s. It’s a purely formal device that, supposedly, has no references other than to itself. What I have tried to do with the grid is attach a narrative to it. In this case, it is an explosion – bomb explosion, somewhere in the city center. Previously, I have done paintings that involve the grid; made up out of sixty or seventy panels, separate units. Divided by the frames, they are situated in a grid-like position. It was a very simplified painting of a brick wall, but the brick wall is actually the length of the brick wall that Winston Churchill built himself for his house. Churchill, as well as being a very keen painter, was also a card-carrying trade union member of the Bricklayers. He published this book called “Painting as a Pastime”. So, hobby, bricklaying, and painting – all seem to go with attaching something onto the grid that people would never think about.

The Renaissance artists used the grid as a form of seeing and understanding things, and marking various points between forms. It is a way of seeing where something is, in relation to something else.

In your work, you often use shape and form in an unusual manner. In classical, canonical painting, shape and form can be taken for granted; yet you decide to position them on the same level, or even above, colour.

I don’t invent any colours, all the colours are given. I like decisions to be made outside of the making of the picture. So that you don’t get involved and then start changing your mind about things. Once you start, there is no deviation or doubt, re-thinking things. Especially with the Ontological Paintings, I just lay the canvas on the floor; cut out the little arrows that I made in cardboard, and then threw them up in the air. Wherever they landed, was the composition. So, I remember that in the 90’s, loads of artists were all painters, and they tried to make paintings where they didn’t actually use the paintbrush. You drip paint, pour it, spray it – any kind of technique – rather than use a paintbrush. So, for me, although I did use the paintbrush, I was also looking for methods where you distance yourself away from making a painting in a conventional way, where you edit things as you progress through the painting.

You also use the method of cropping, which was famously used by Impressionists, inspired by the early photographs.

Degas was the first artist who used photography in a way where elements were framed. So the idea of cropping was used. His assistant was Walter Sickert, and he became famous in his paintings for the severe and unusual crops that he did. There is also Andy Warhol – who presented things straight from society and supermarkets.

I like the idea of cropping. It is infinite. You can make hundreds, possibly more, thousands of different images from one static image – if you crop it differently. I did some paintings based on Raoul Dufy. He painted thousands of oil paintings, with a view of La Promenade des Anglais, in Nice, and he would then move his stool about six inches to the right, and get a new canvas, and paint the old scene all over again. So, basically, what he was doing, was continuously cropping the scene that was in front of his eyes. He never thought to himself – “am I just repeating myself?”. He just saw it as a fresh thing, at the time.

Is that how you feel as well?

Yes, I don’t feel like that has exhausted it. The more microscopic you go, the more you inflate them – that creates infinite combinations.

You use so many different techniques and materials in your work. You write, you work with the existing objects – do you think that all of these different methods coincide?

They do! If you have an idea, you have to ask yourself: “what is the best way of putting that idea across?” With the bronze trees that I did – Burgess Park – originally, I had seen the image, the painting by Marsden Hartley, of a fallen tree, and then that immediately made me connect with all these damaged trees in the street. I saw an image by Caspar David Friedrich, of one tree, standing alone in the large landscape, and I thought of trying to paint one of these trees in London, in the style of Caspar David Friedrich. I then realised, that I did not have the skill, the ability to do that. The best way of getting the idea across was to take the real thing, the real tree.

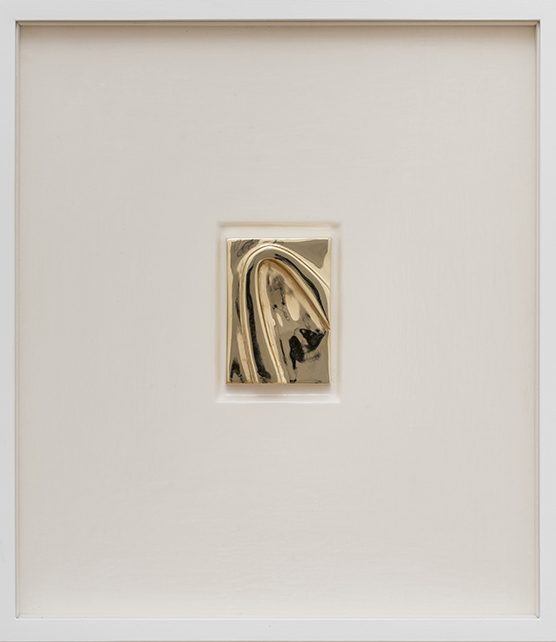

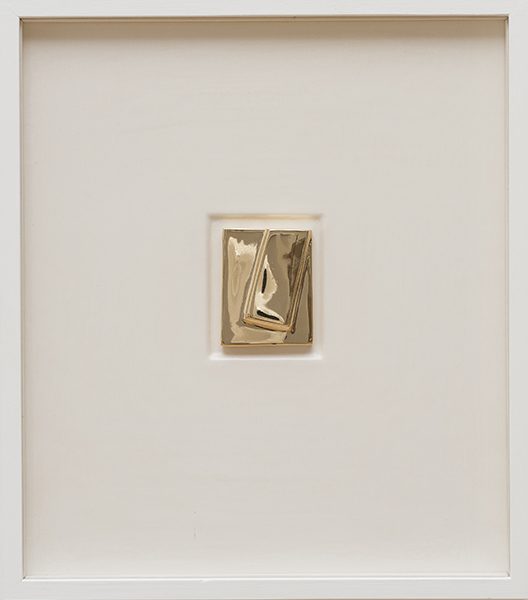

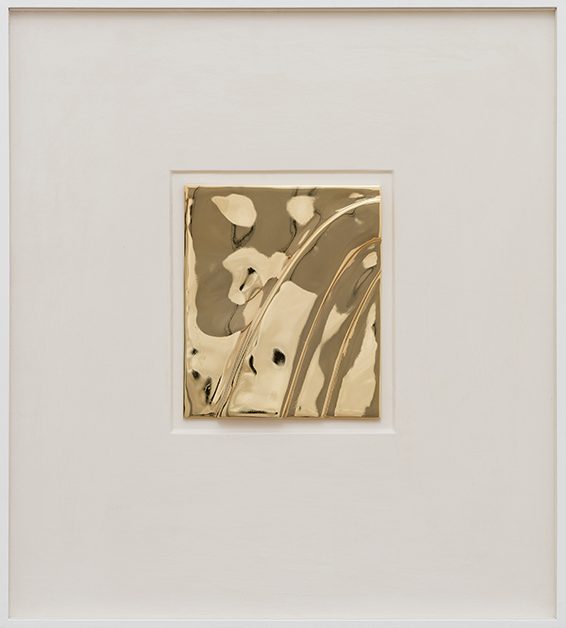

Golden Arches IX (2016)

Golden Arches X (2016)

Golden Arches III (2016)

Golden Arches VIII (2016)

Golden Arches XIII (2016)

“If you have an idea, you have to ask yourself: “what is the best way of putting that idea across?””

Throughout your whole work, you say that you examine questions of modernity and you apply it to the contemporary. Yet, I was wondering, now that so many -isms are changing and moving forward, do you think that the ideas and the ideals of modernism will still be relevant, or do we have to look at, at least, postmodernism?

Modernism is like a tree, and there are all these branches coming off it. The exploration of those different branches are the postmodernist directions. I simply have nostalgia for the journey that modernism went on to.

Before postmodernism, no one did paintings of helicopters or airplanes, because they were seen as an unsightly things to have in a picture. There are no parameters there, and I think that sometimes it just leads to decorative or design. When I was at art college, there were phrases used which you would put down somebody’s work, by saying “it’s decorative”, or “it’s illustrative”. With modernism, you have got basic things – shape, line, form, colour. Building solid things, rather than a painting that has got a thousand helicopters and humming birds in it. It seems nonsense to me.

Any work could be considered decorative and illustrative, though.

Yes, but to be a good artist, you do not need to be able to draw something really well, in the way that the illustrator can. Something really similar could have a very powerful effect. I would sooner look at Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII than read four copies of graphics annuals. It seems like a lot of art nowadays looks a bit like pages from these graphic annuals.

You said that gold is “ennobling the ignoble”, in relation to Junk. The application of gold comes from a very ancient tradition – Antiquity, Egypt. Is it a critique or a compliment for the culture of consumerism and McDonalds?

It is actually a bit of a critique about contemporary art. Awful lot of shiny art is being produced, and art audience has changed – from late 80s and early 90s, people who wrote for the art magazines formed the value of the piece of work.

Now, it’s just simply about sales figures – how well it stands at the auction, and no one cares what is written anymore. If you can sell a show completely, you can say whatever you like, in the most derogatory fashion, it won’t make any difference at all.

Ennoble and ignoble – I am always looking for things that appear worthless. Through art and the transformative power of art they can be seen afresh. That is an important thing about art, that it should be able to transform material and ideas into something else. And if it does not do that, it kind of fails. It can be the most well-intentioned idea, but if you cannot transform it into something, than it is no good.

Not many people are actually aware of the fact that you are an exceptional curator. There was no catalogue for the Peeping Tom exhibition, and there is barely any information about it on the net.

The idea for that show was the love of looking. There was someone whose work had to be hung high, so that the children would not be able to see it.

Do you think that being an artist helped you in your role as a curator?

Yes, because I knew a lot of those people. Recently, I curated an exhibition in Cape Town, where I just took British Artists who work on paper, and just put all these works inside a suitcase and took them over there, and then got them framed. They asked me at the customs what these pieces were, and they were from about fifty artists. I said they were all mine, and that I worked in different styles. It seemed to work!

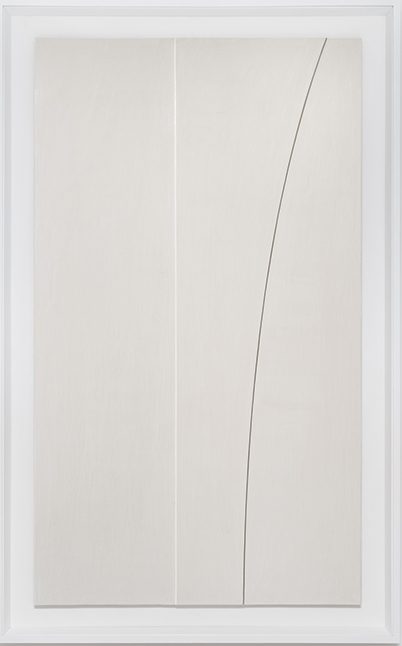

Pure Junk XI (2016)

Pure Junk VI (2016)

Pure Junk IX (2016)

Pure Junk II (2015)

“To be a good artist, you do not need to be able to draw something really well, in the way that the illustrator can. Something really similar could have a very powerful effect.”

I always found it very interesting that during Sensations exhibition, all artists were almost divided into sectors. There were the Young British Artists, and the artists whose work was in the Saatchi’s collection.

They were all in the collection of Saatchi.

Yes, but the second “sector” was not part of YBA. Your work is, most definitely, very different from work by YBAs. Did you ever want to join them, though?

Well, I was ten years older. But I was a friend of one of them – Michael Landy. I never wanted to join them, no; I had my own ideas and carried on with them. It was just the timing – I got my first exhibition at the same time when they just started. I did a number of exhibitions with Sarah Lucas, Gillian Wearing, Jeremy Deller, Mark Wallinger, Fiona Banner.

You interacted with the younger artists, but how about now? Do you still interact?

Yeah, I do actually.

In what way? Collaboration or mentoring?

I neither collaborate, nor mentor. Only by example.

Would you agree that now is a particularly difficult time for young artists?

Very difficult, yes. My studio was a squat, I had about ten rooms. I didn’t have to pay anything, but now – it must be the way that gentrification operates – the rising cost of studios, and it is quite a commitment, to have one. Years back, all these big studio blocks were all empty, because people were out at work, trying to pay for their studio that they never used. It was still necessary for them because without the studio they did not feel that they were artists. But as they were not making anything… They were probably not artists. I think you have to make something, to be an artist.

During the Frieze 2015, there was a panel conversation, that was called “Can Artists Still Afford to Live in London?” Many people found that event extremely problematic, because it was taking place at a very expensive, bourgeois art fair. So, the audience of that conversation was not students, but people who were interested in visiting Frieze Art Fair, and could afford it. But the question is actually different – can artists still afford to be artists?

Not really. Unless they are happy to work from their home, off their kitchen table. They can still have ideas, you can still produce drawings, collages. Whether the studio is necessary – I don’t know. It must be very difficult. All the studios around this area – Broadway Market, Bethnal Green – they had all risen the rents by a 100%. So there has been an exodus of artists now looking for cheaper areas, going to north Tottenham, beyond Archway.

What would be your main advice for the art students who are graduating?

Work on paper. You won’t need much storage space. Think about how you can present things. Don’t create too much baggage. Be free – go to different places. Have notebooks, like a writer. Doing and thinking is more important than making great big finished pieces.