“YOU ARE SORT OF TOLD AT ART SCHOOL THAT YOU CAN ONLY ACHIEVE SOMETHING THROUGH EXPERIMENTATION, WHICH IS GENERALLY ACCEPTING LOADS OF FAILURE.”

You grew up in the South East – how has your background influenced your work?

The car (Chavy Boy) directly references the place that I come from. My dad was a banger racer, it’s something that is particularly provincial. Also the language on it (Cheers Mush) is Kentish slang.

The Daimler jag limo references this new surrounding which I find myself in. But through plastering and bastardising it, it’s like claiming it as your own. Referencing my family situation and my place there whilst being here is something that I do quite readily.

Your work has humour, but also I think it’s very personal. Specifically, ‘The canapes will be great.’ Is it important for your work to use irony to translate emotions?

Rather than irony, it’s more about an honesty, a duality, or a contradiction in the work. It’s more in reference to there being two sides to every issue. ‘The canapes will be great’, was in reference to the reason why someone said I should be in a show. And the show sounded terrible, but their end thing was ‘the canapes will be great’. It’s such a stupid thing to say, and it sort of pissed me off. So there are usually two functions in my work.

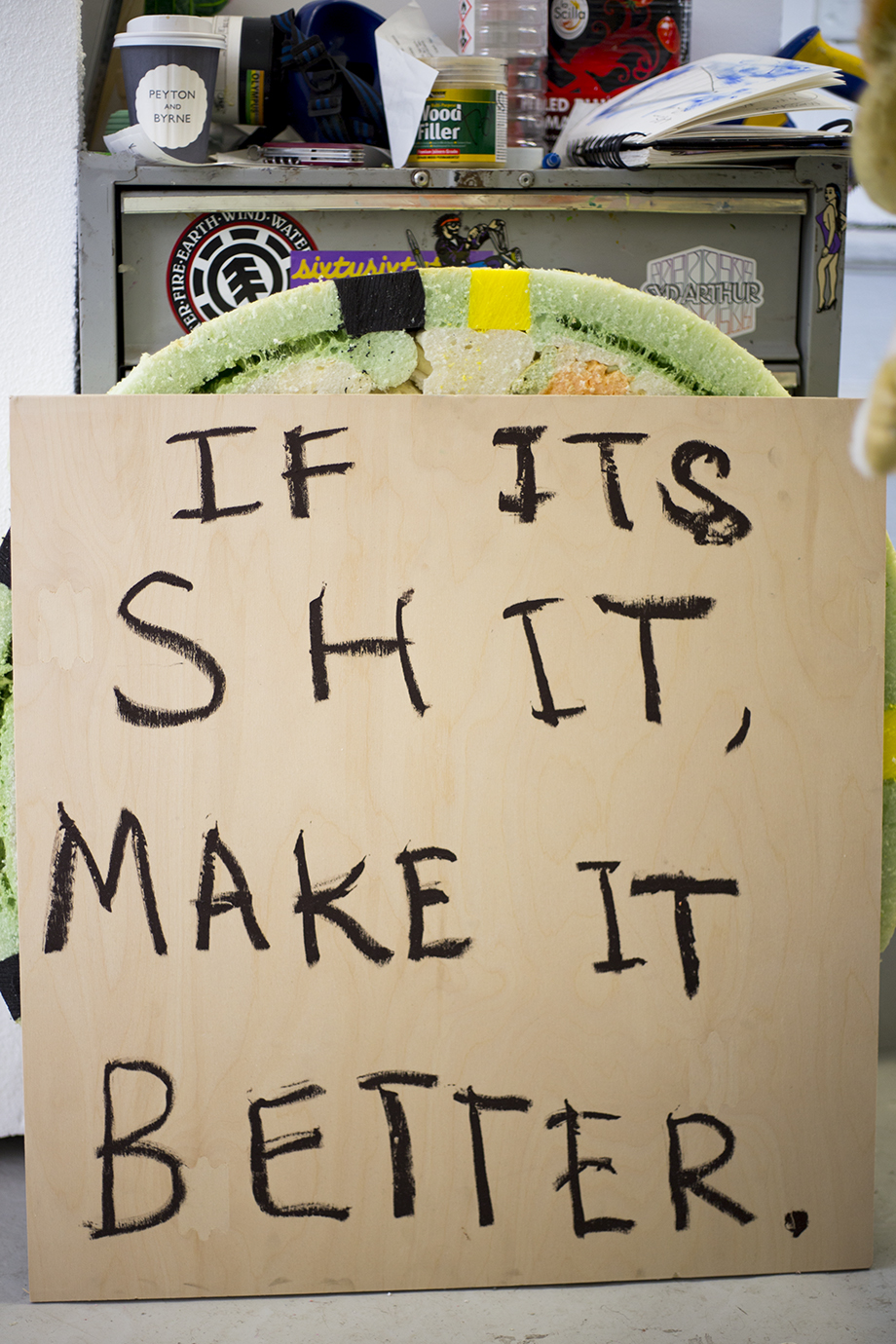

Also my piece ‘Everything’s totally fucked’ is on a crappy piece of polystyrene, but I’m in the cushiest position that I’m ever going to find myself in as a student maker. Also my work ‘Daisy in Progress’ is a trolley that is full of failed sculptures, and it references that you are sort of told at art school that you can only achieve something through experimentation, which is generally accepting loads of failure. By piling failure on top of each other, you end up with something that’s maybe some kind of success. Contradictions are the big thing.

Chavy Boy was one of my favourite works in the Interim Show, and also one of the most memorable, where did your inspiration come from for this piece?

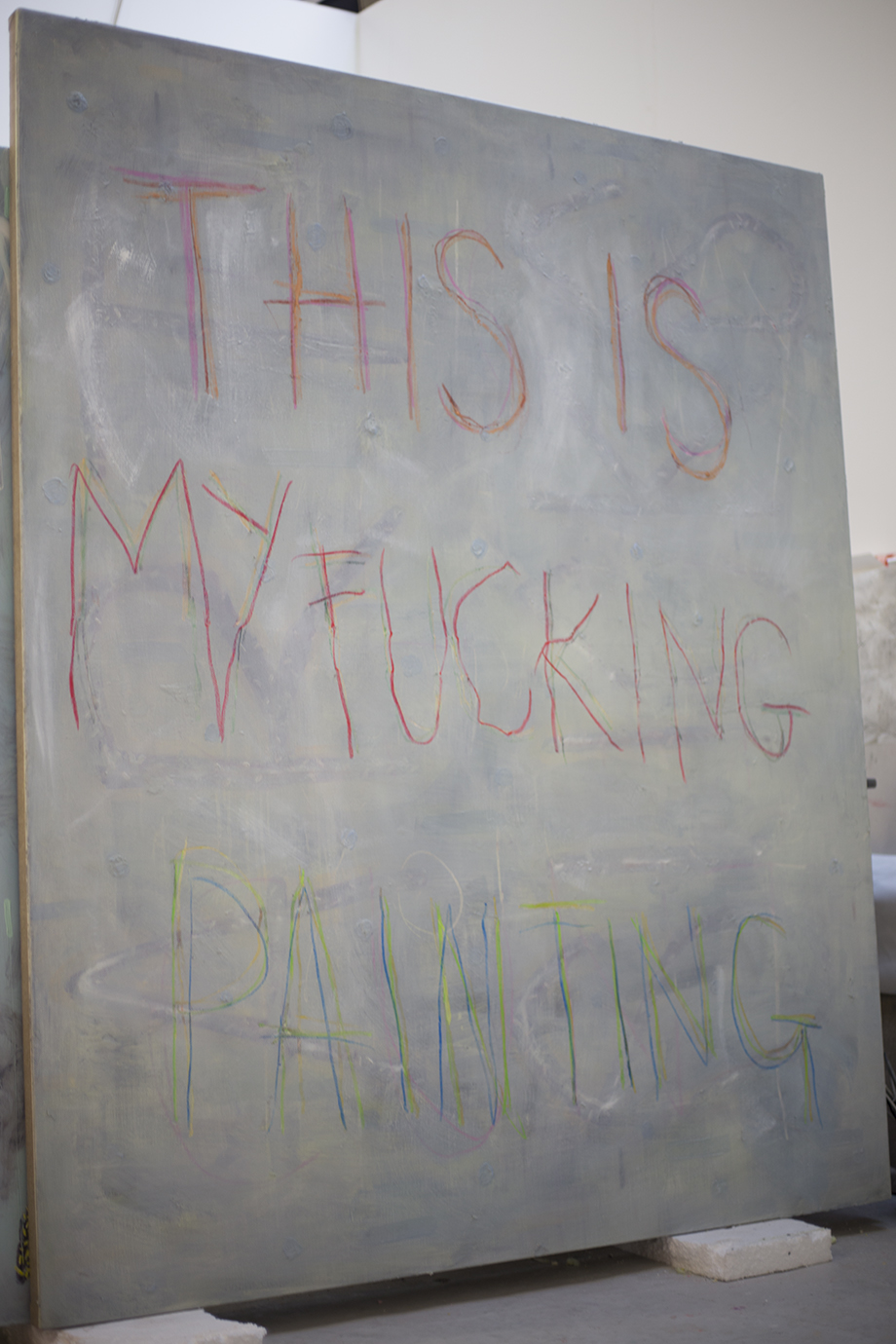

Chavy boy was a response to the idea they wanted to do a Royal Academy takeover. I instantly thought: what would I do? what do I want in the courtyard? The servitude of an artist keeps coming up, who do you make the work for? Who is it serving? Is it serving a public, is it self-serving? I’ve been turning loads of my sculptures into reclining chairs to serve myself in the studio and I’ve always seen it as a real selfish egotistical practice. You make something and then you invite loads of people to come and look at how great it is, for me it’s a funny thing.

Do you not think that art’s service can be to affect its audience?

But even that comes down to an ego thing. Even if you try to do it in the most humble way possible. Humbly arrogant is a term I keep bandy-ing around as a joke. I try to remain aware of those situations, and then you can have a lot of fun with it.

In your artist’s statement you mention that you “strive to make contact with the human condition, or more specifically the artistic condition.” What do you mean by this?

It’s the existentialist idea of the human condition, that everything is running in cycles, one minute you’re up and the next minute you’re down – in retrospect maybe everything doesn’t seem as bad as it does at the time, and the dramas of your life can turn into this soup of the past. The artistic condition is slightly different – in terms of dealing with something through making, something I want to approach in my work is the energy that I feed off in life.

…And I wondered what you thought about the notion of the artist as ‘creative genius’, something different to the average person?

Genius? I think it’s more about graft. A lot of people have good ideas. I think it’s more about graft and courage, it’s the will to act. If you don’t act on any of your ‘genius’, or impulse, then it’s pointless.

Well, yeah, you have to work hard to get where you want to get in life…

Yeah, I designed my own masters program before I came here, because I knew I wouldn’t be able to afford to do a masters. And one of the big pieces of work I made in the program was a mantra that was hanging in my studio, which said: ‘Must work harder.’ Which is a reference to the George Orwell book Animal Farm. Where Boxer, the shire horse flogs himself to death whilst working for the greater cause, and then they end up sending him to the glue factory. It’s good to be self-aware as an artist and to be comfortable with the idea of massive failure, then you can get on with it. It frees you up a lot. And that’s something which has stuck with me a lot.

“THE TUTORS ARE BETTER THAN THE CANAPÉS.”

How has the RA pushed your work to develop further? And do you think you’d be making the same work if you hadn’t started the course?

The work has changed – I got here and had a complete breakdown. I realised working in a studio on your own, marching to the beat of your own drum is easier. Being here, it took me a long time to adjust, it wasn’t until the second term that I even felt comfortable making here. I didn’t know what to reference – when all of your work is about struggling in a freezing cold unit, writing your own program, very DIY, ‘I’ll do it against any odds.’ And then the RA sweep you up, and are like “hey come on in, it’s lush ‘the canapes are great.” My whole thing was: how do you function when you’ve been given this meal ticket? So in that way it’s really pushed me, because it’s put me in this different environment. And the whole school body and the other students here, the tutors are great – the tutors are better than the canapes.

So after the big lead up to the interim show, what are you working on now?

The next thing is hopefully a solo show in the summer that will be a collection of paintings and sculpture, a new collaboration with Raven Bush that will be sound and sculpture and hopefully utilizing this new sustainable energy technology that we will try and push.