“IT’S ALL ABOUT EXPERIENCING EXHIBITING YOUR WORK, AND COLLABORATING WITH LIKE-MINDED PEOPLE.”

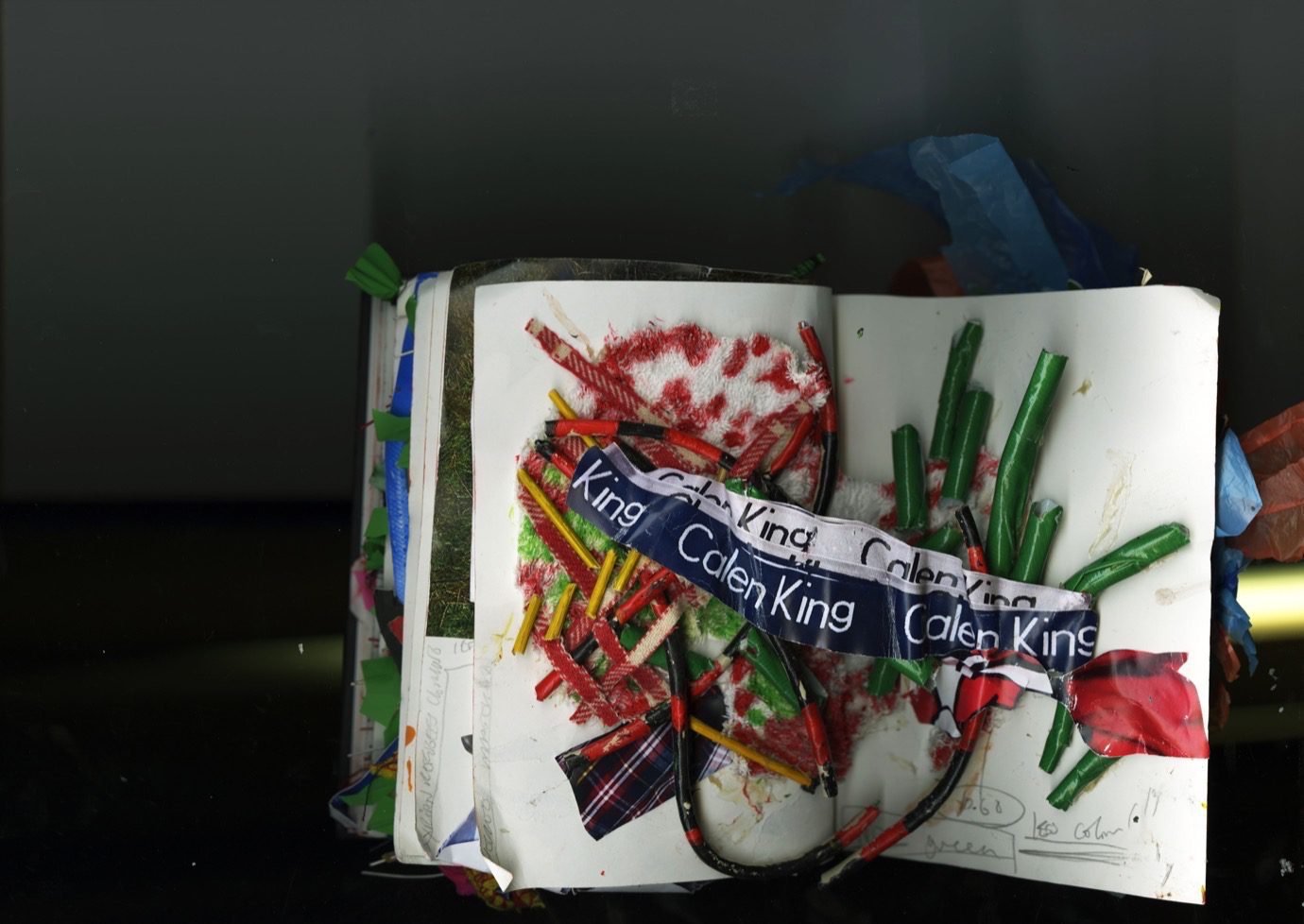

The evening commenced stood in the garden with a beer, looking over the work of Ellie Pennick, a Fine Art student at Chelsea. Within her practice, she frequently explores social-political issues, as she has in this piece, which revolved around the housing crisis in Britain. The result is an aesthetically-pleasing collage of assembled objects collected from an estate in Peckham. Behind this, a film created by Ellie Bartlett is projected, which underlies the collaborative nature of the exhibition. Having grown up on a now-non existent estate in a mining town near Leeds, this subject is integral for the artist, who sees the same pattern of gentrification and displacement within London. “It’s a really shit situation and the government seems to be hiding it quite well”.

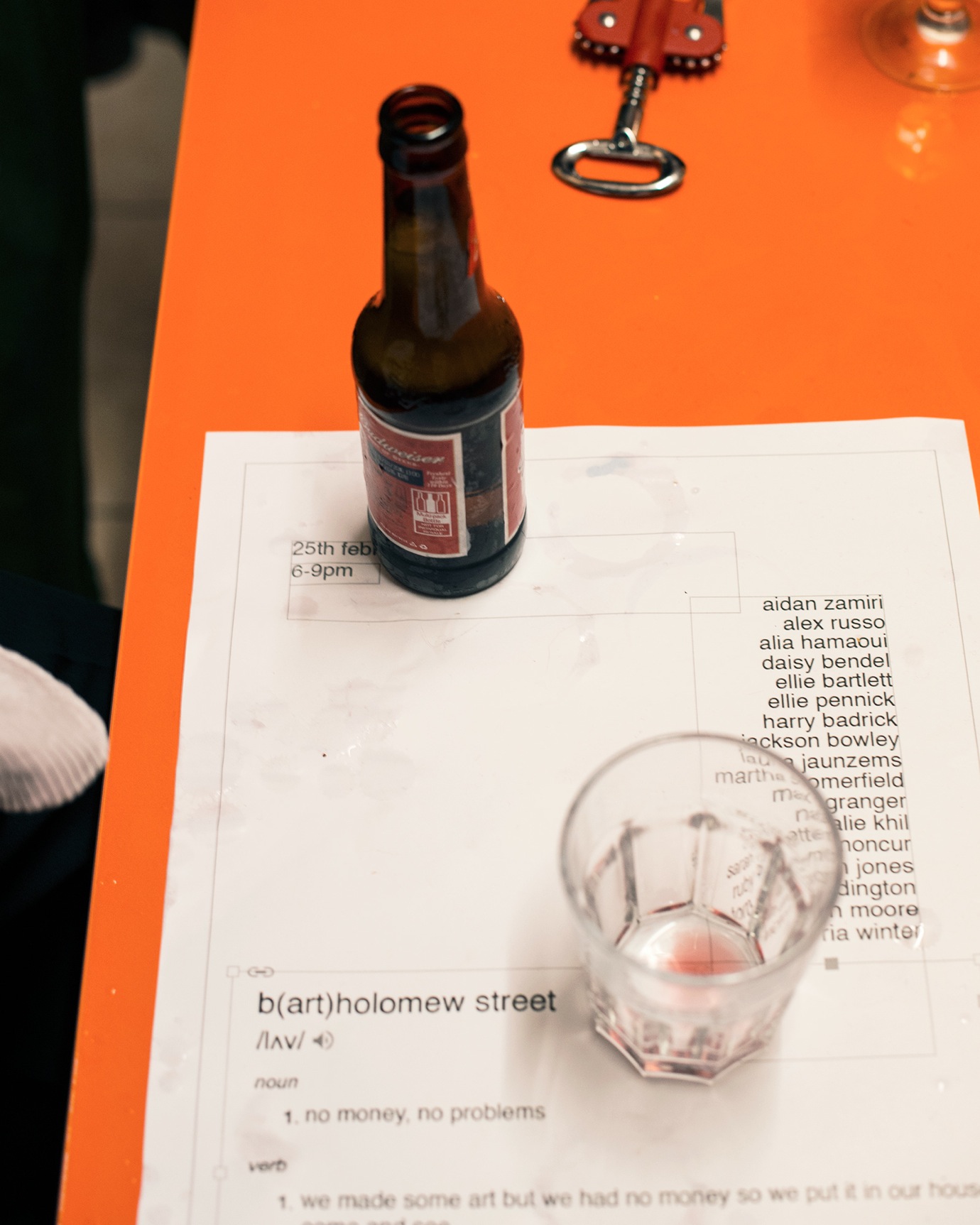

Across the exhibition, the work varies greatly: from Natalie Khil’s graphic exploration of life after Zayn left One Direction (did you know there were 7 suicides when this happened?) to Ruby Boddington’s expression of silence being the negative space of sound: the individualism of all the contributors is effectively unified within the space. The aim? “To make a point that even if you can’t afford a space, you can still work with what you’ve got.” Ellie Bartlett tells me. “It’s all about experiencing exhibiting your work, and collaborating with like-minded people,” Natalie adds.