“A LOT OF PEOPLE THINK THEY NEED A BUSINESS PLAN AND INVESTORS, AND YOU CAN’T GET INTO THAT MINDSET OR YOU JUST WON’T EVER DO ANYTHING.”

What do you think are the keys to a good publication?

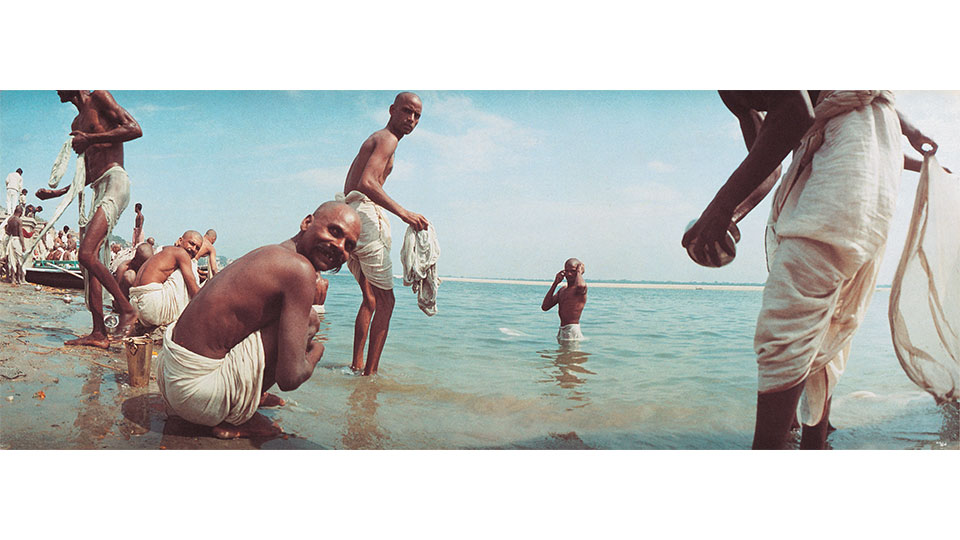

I think a “good publication” is an experience – something you want to keep and revisit and share with others – and we are in a world right now that’s challenging the publishing industry to reinvent itself. Many of the traditional print magazines out there could be online-only, and the Internet is a great thing. There’s so much information at your fingertips; at the same time, there’s so much going on that you have to either be a very good curator, or rely on other people to edit the experience for you. Magazines, after all, are edited. It’s a subjective version of what someone finds interesting about the world.

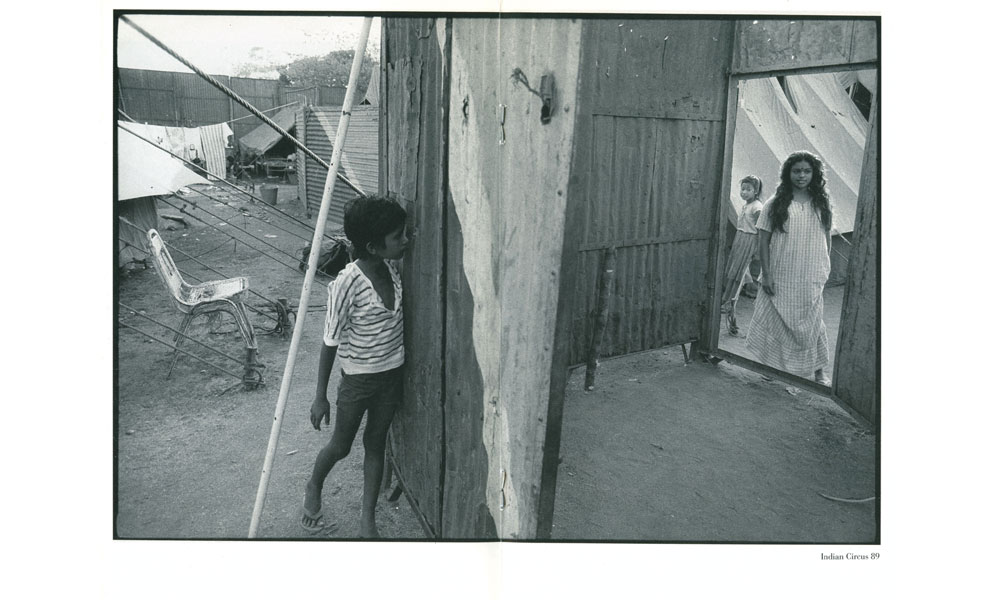

Mainly, I don’t believe in disposability. Printing is harmful to the environment – the loss of trees, the use of toxic inks, massive amounts of shipping – so you have to question the endeavour. You have to make it worth the effort.

What do you think should be printed?

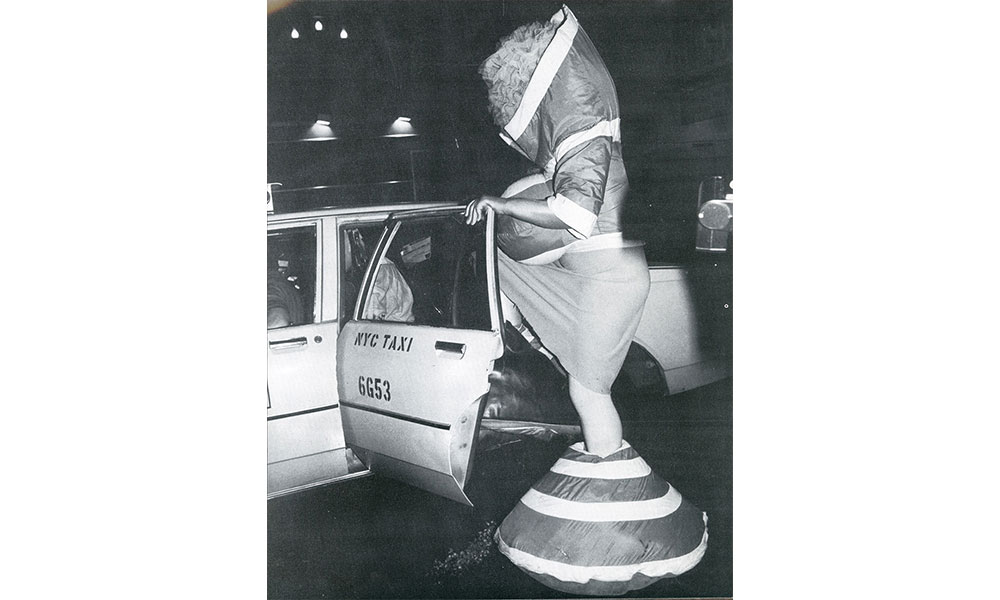

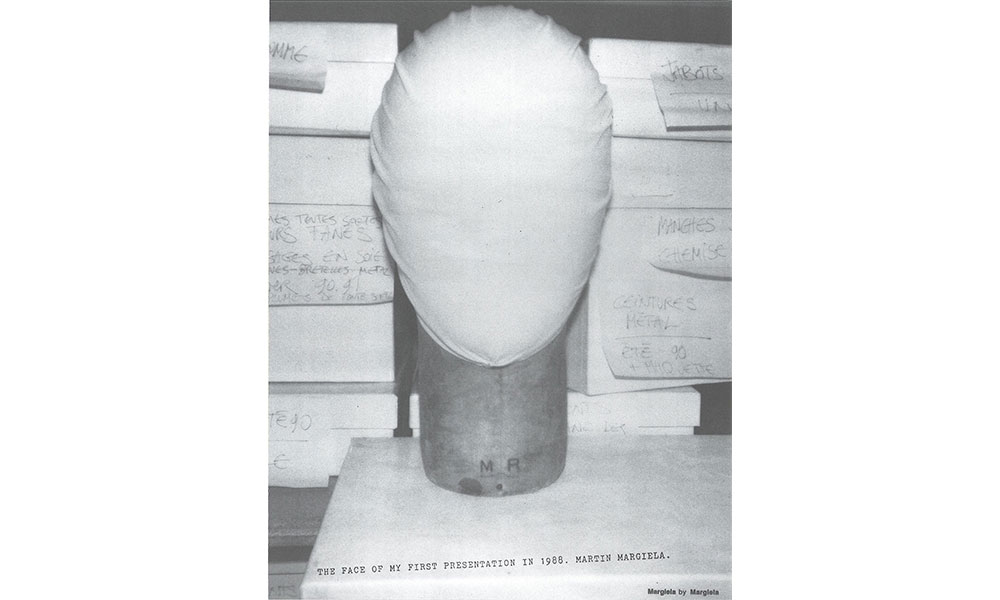

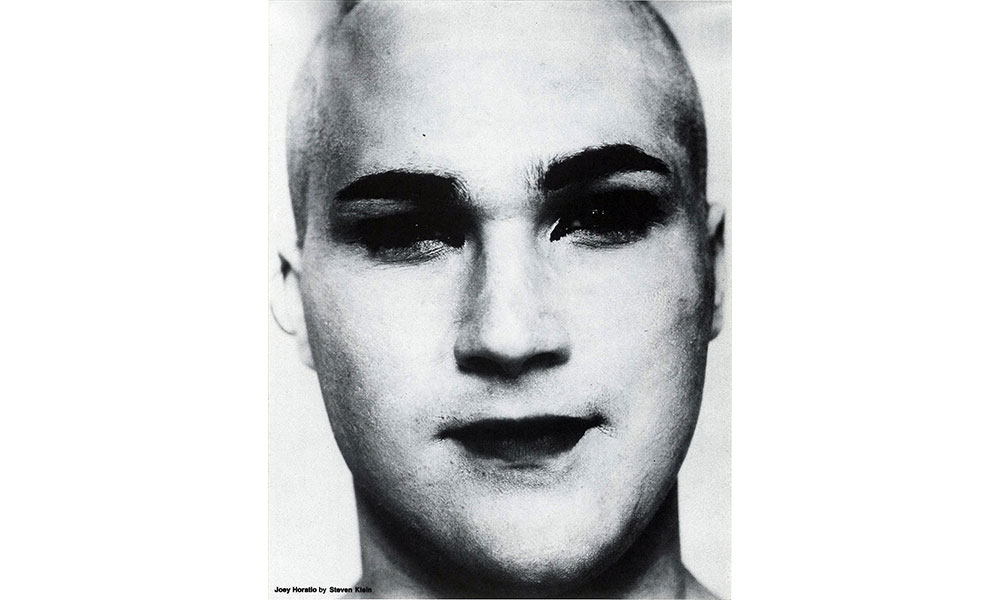

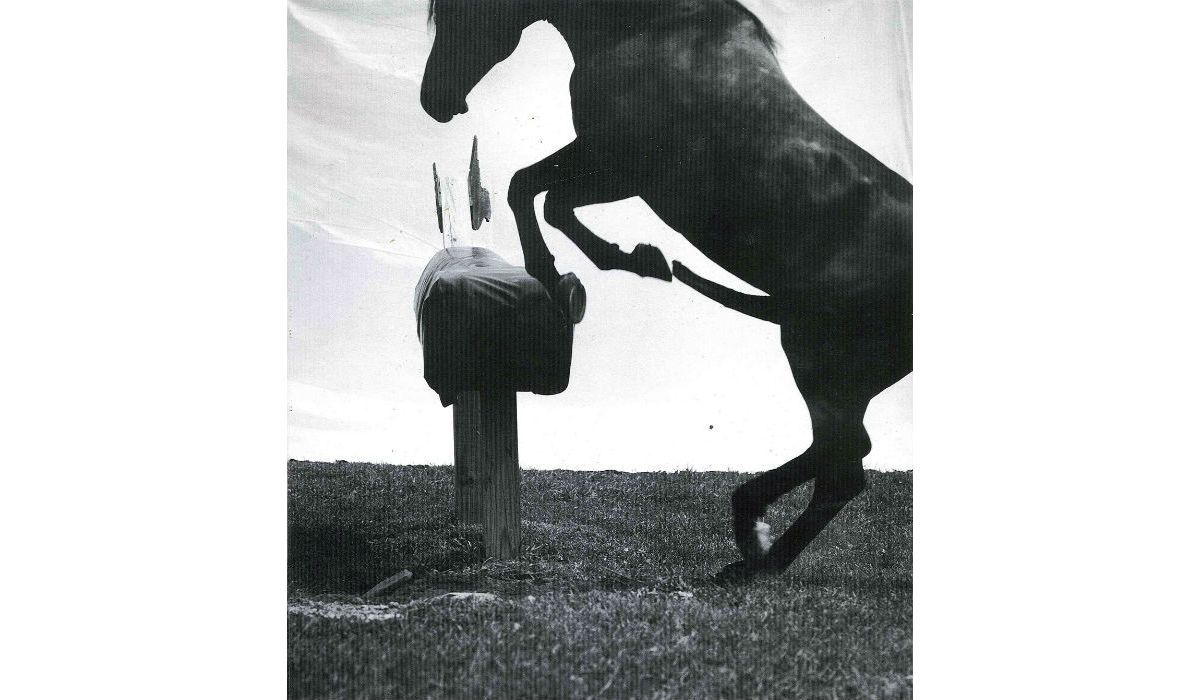

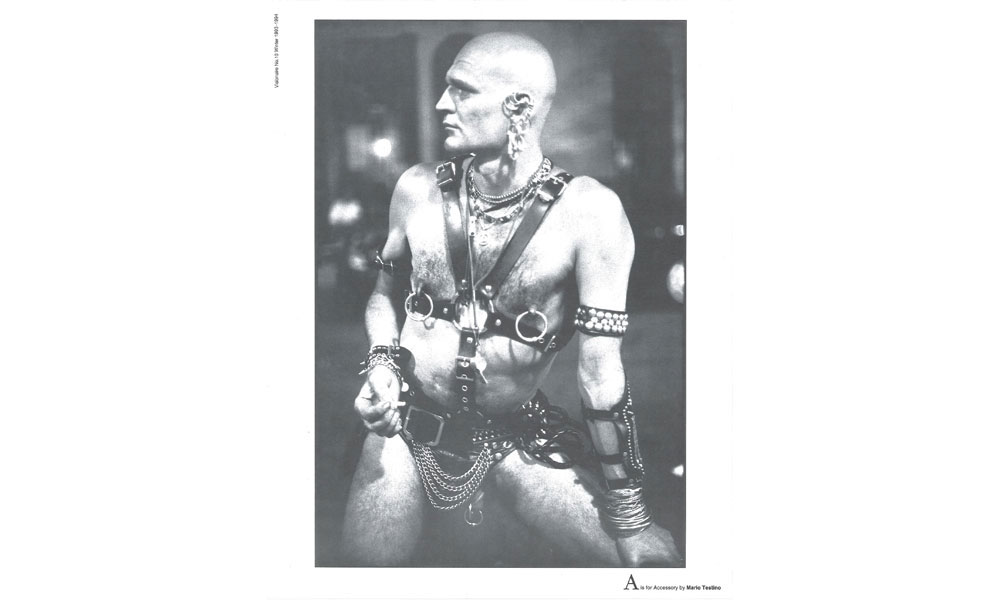

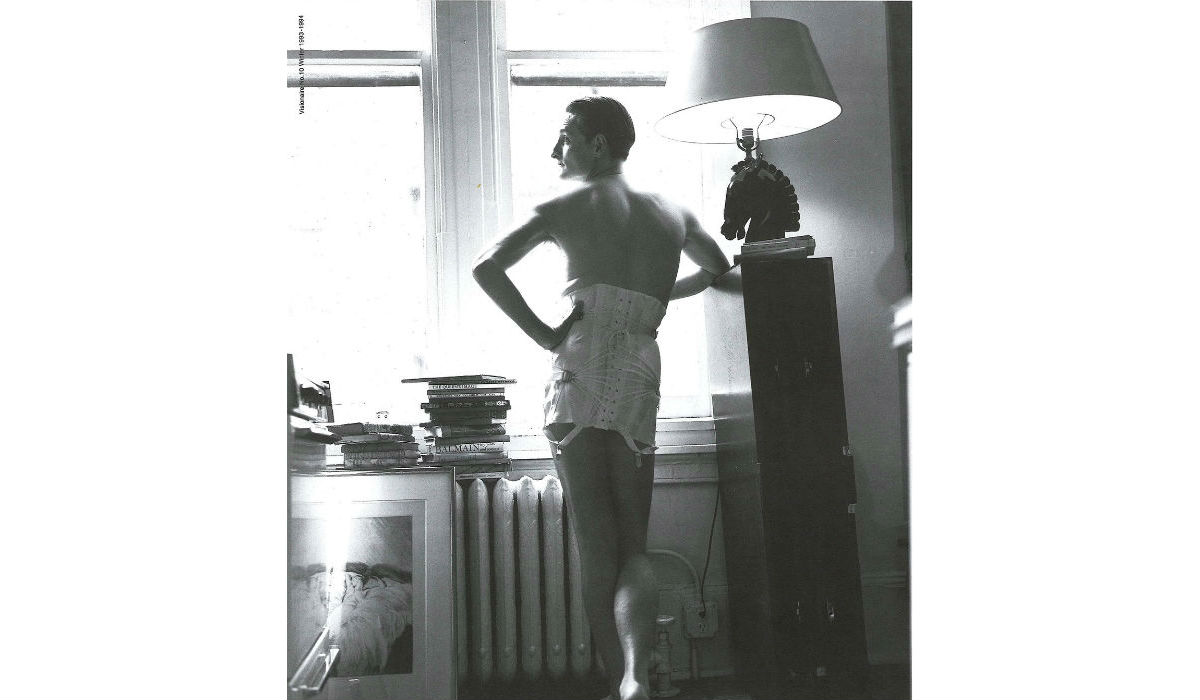

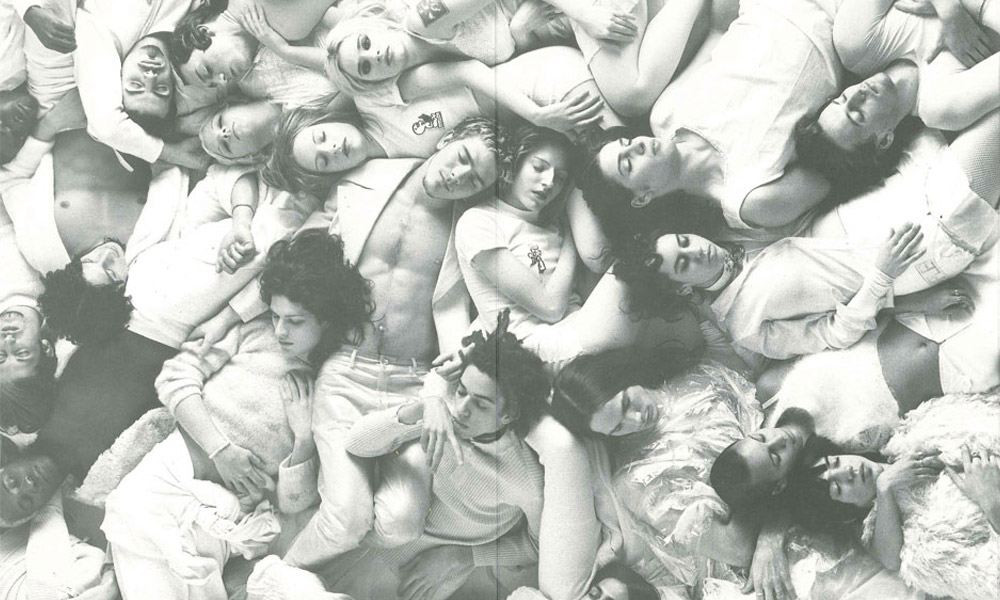

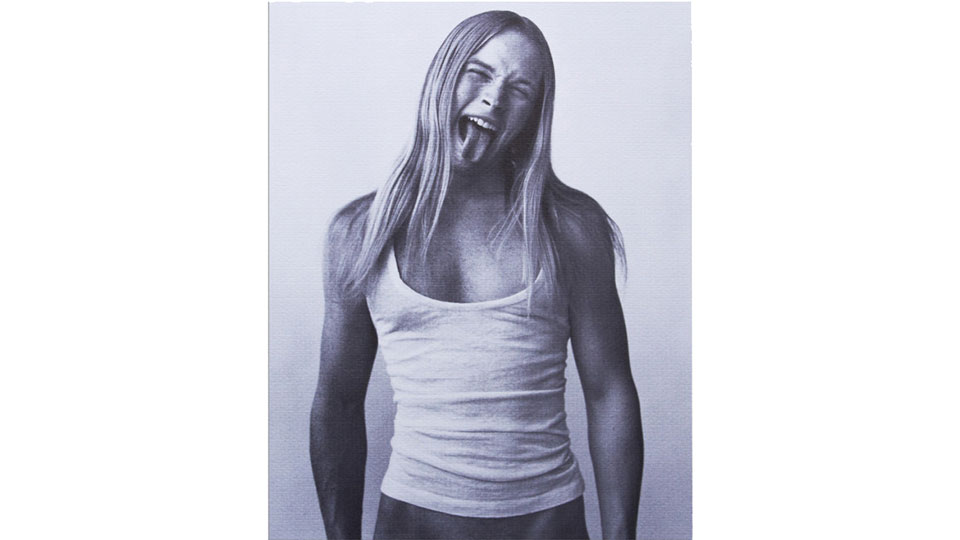

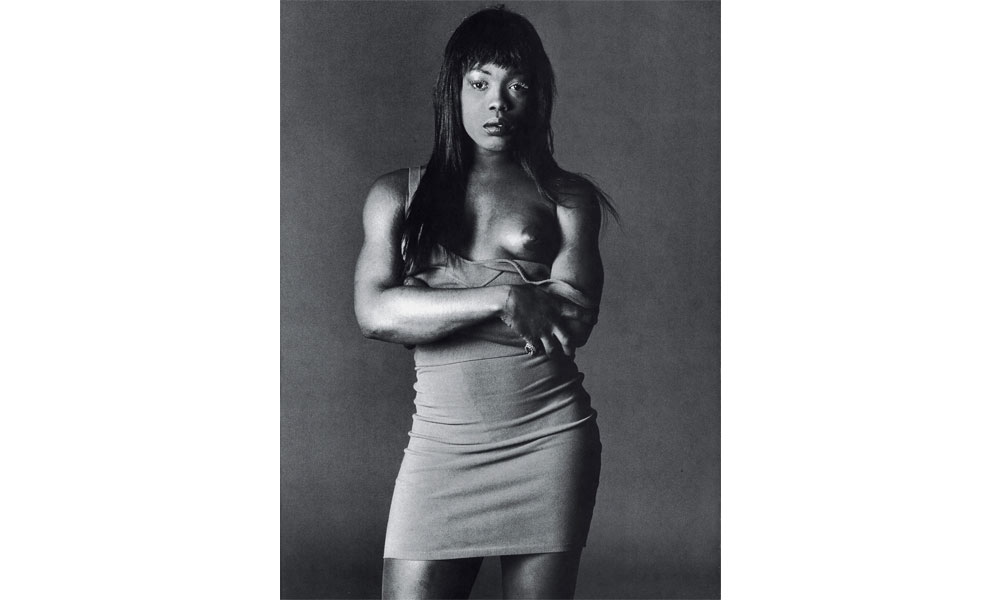

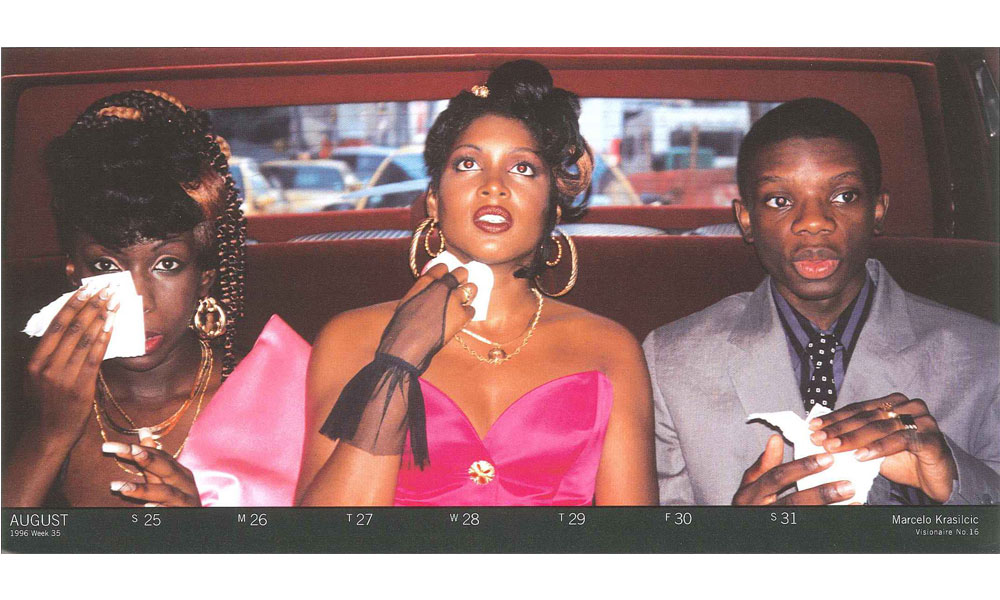

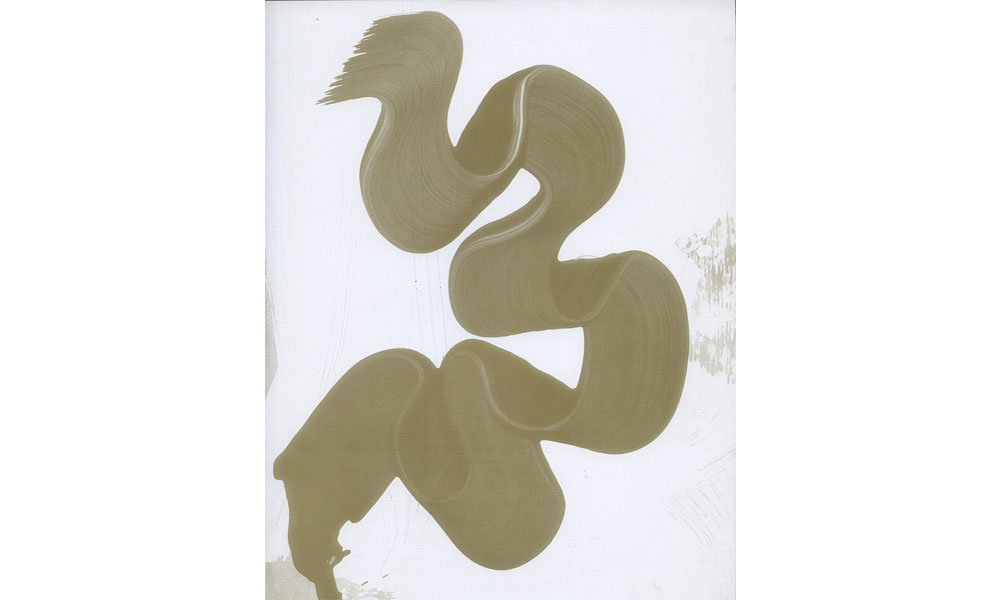

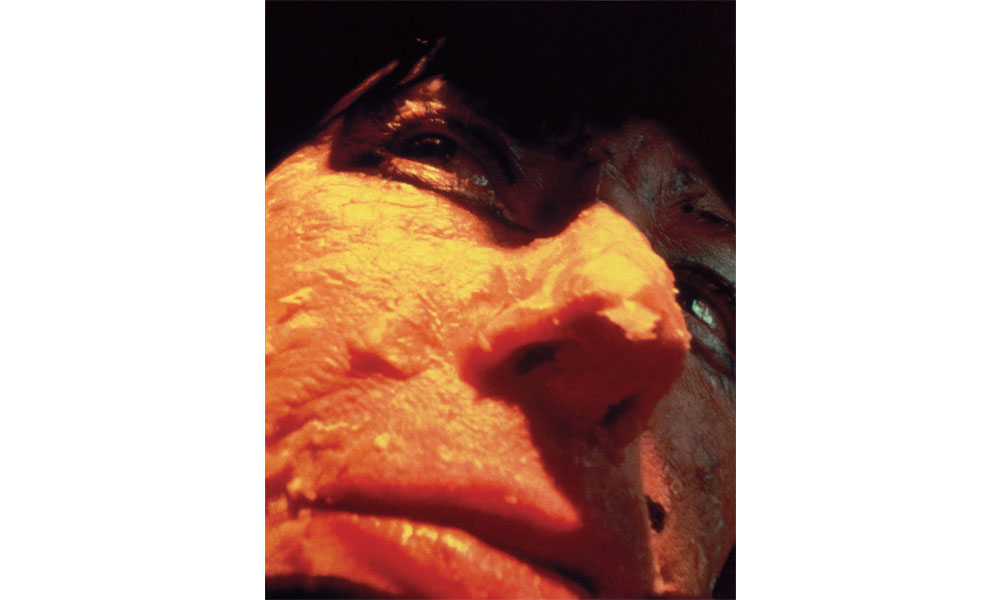

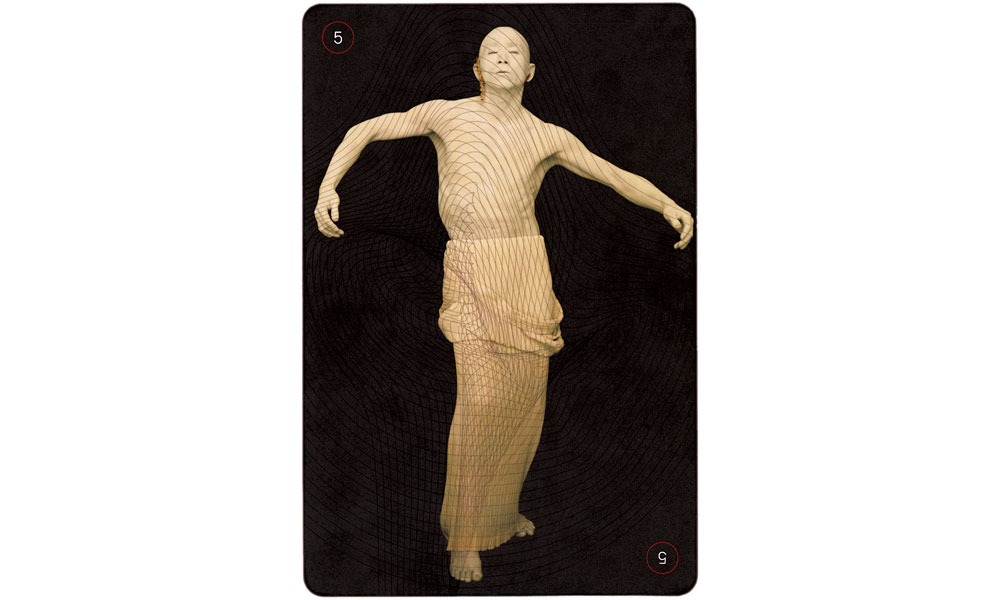

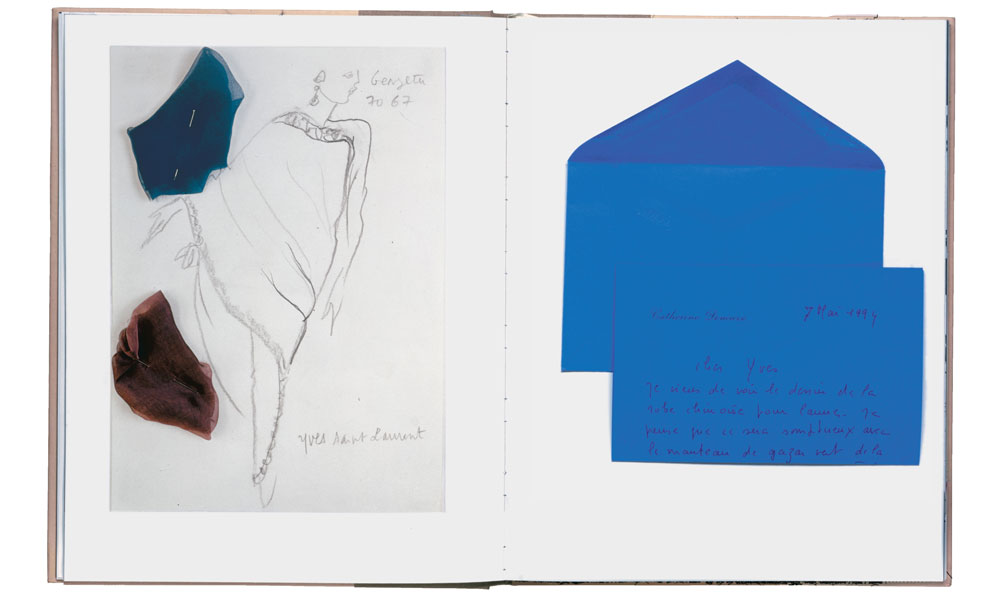

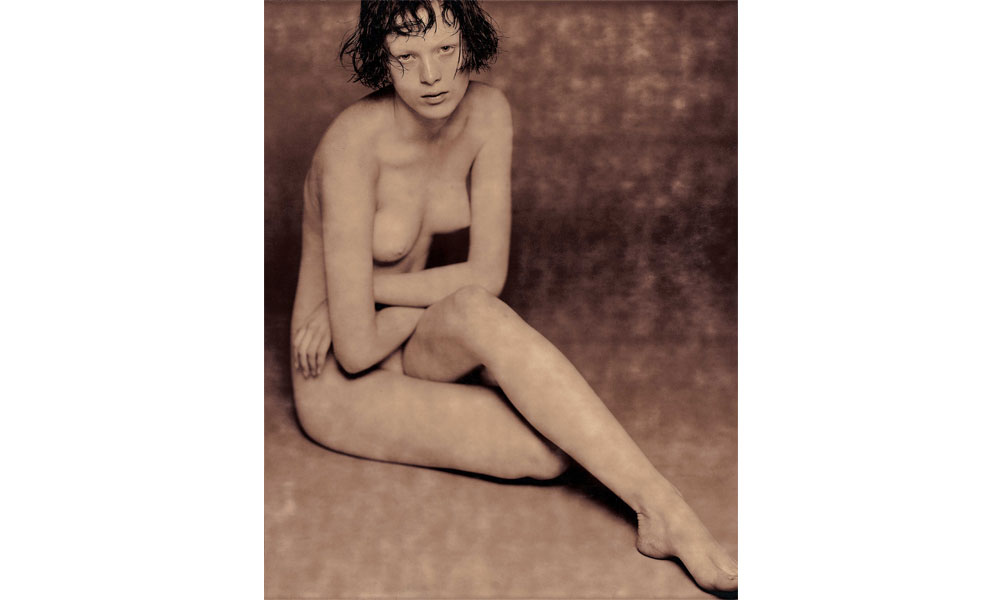

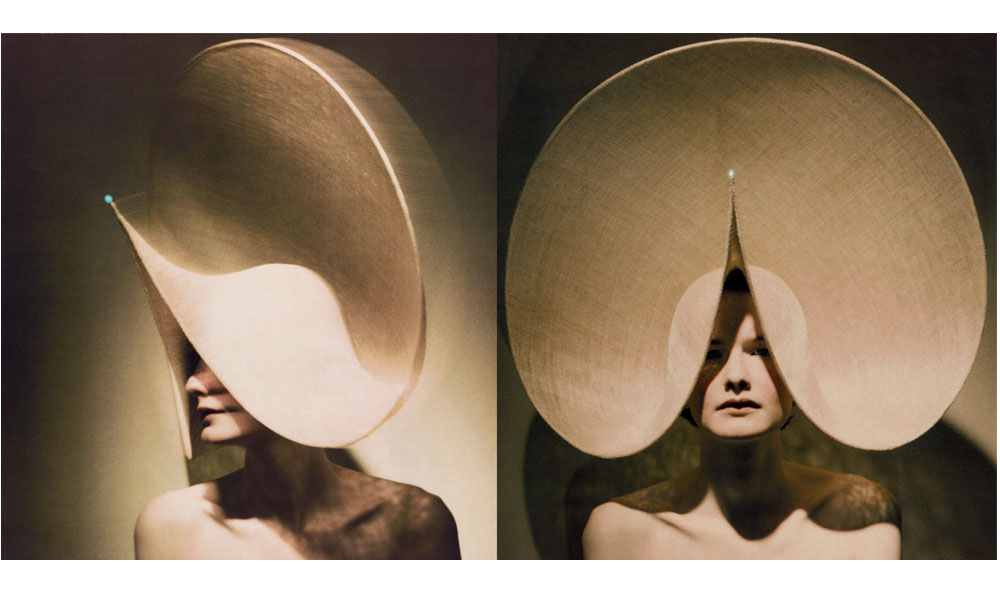

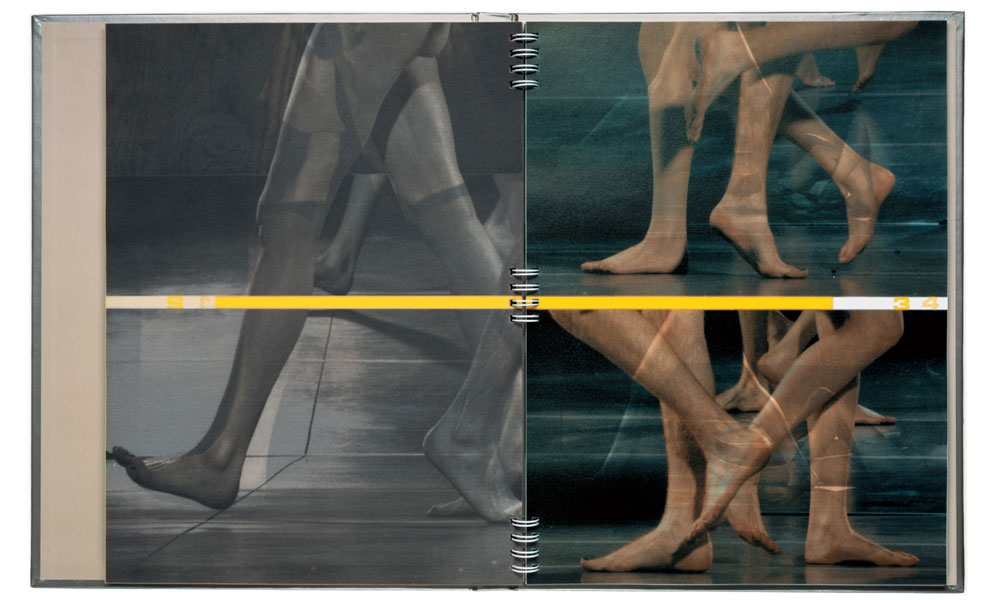

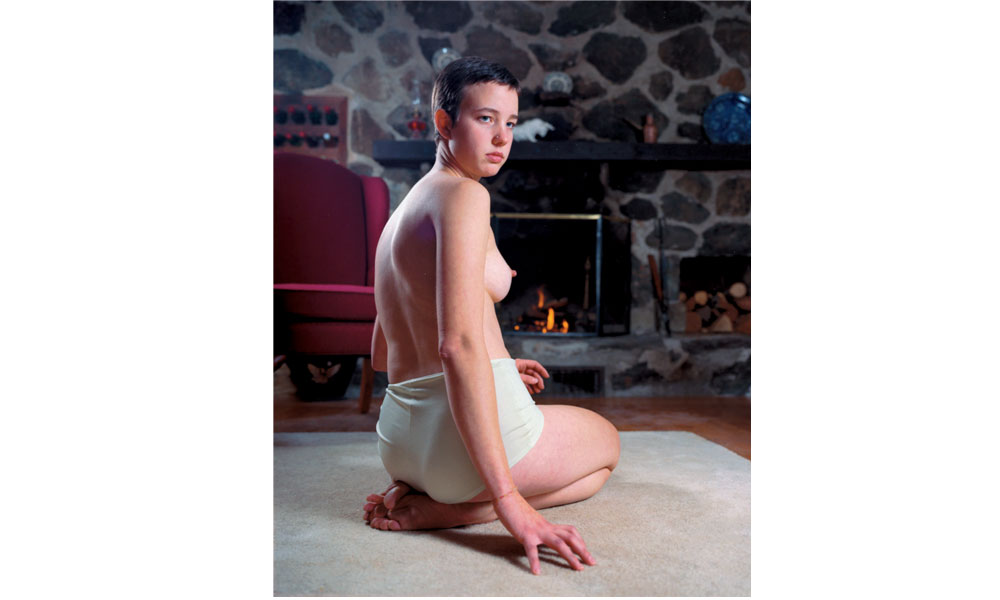

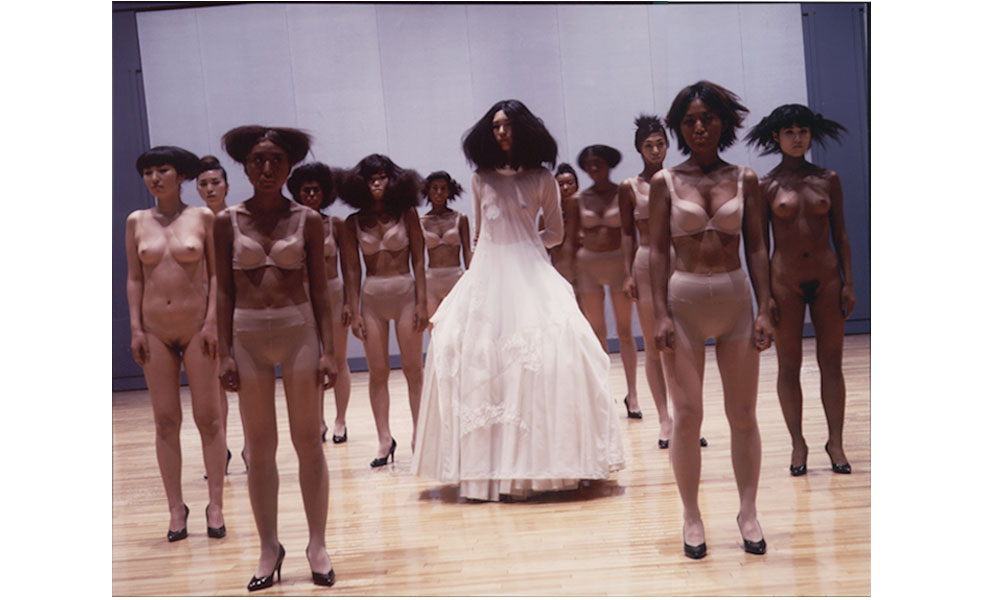

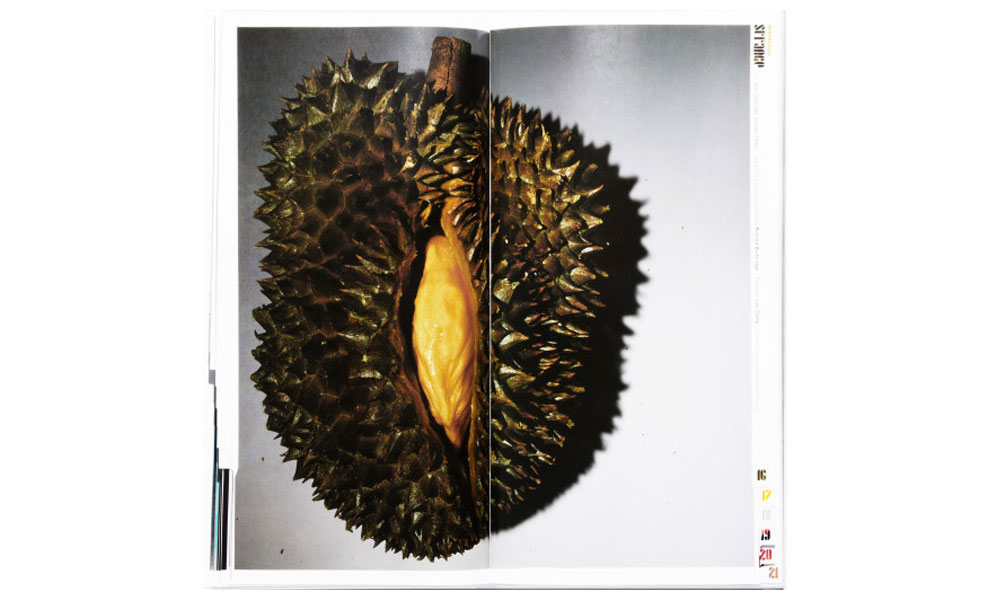

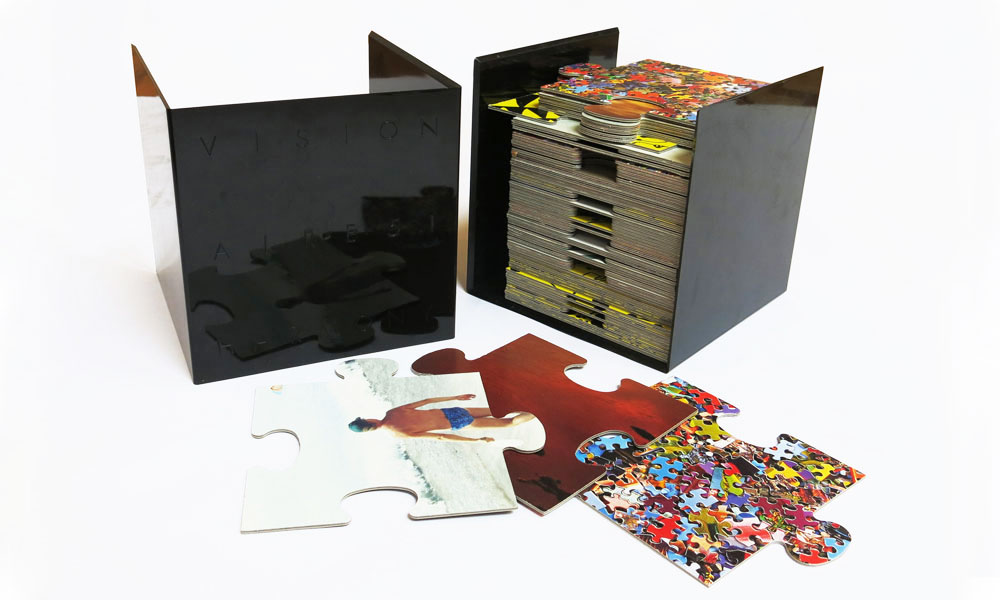

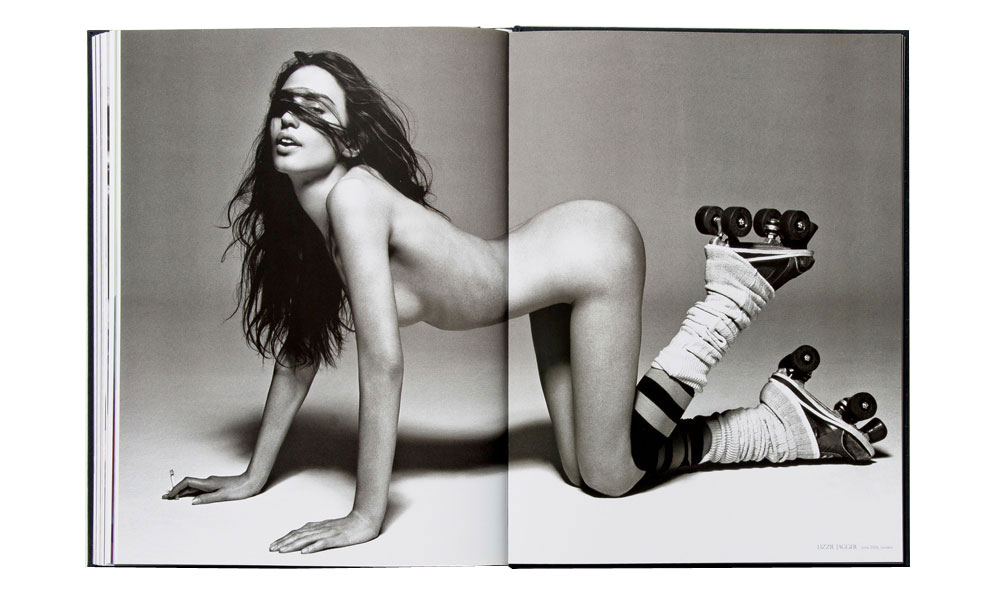

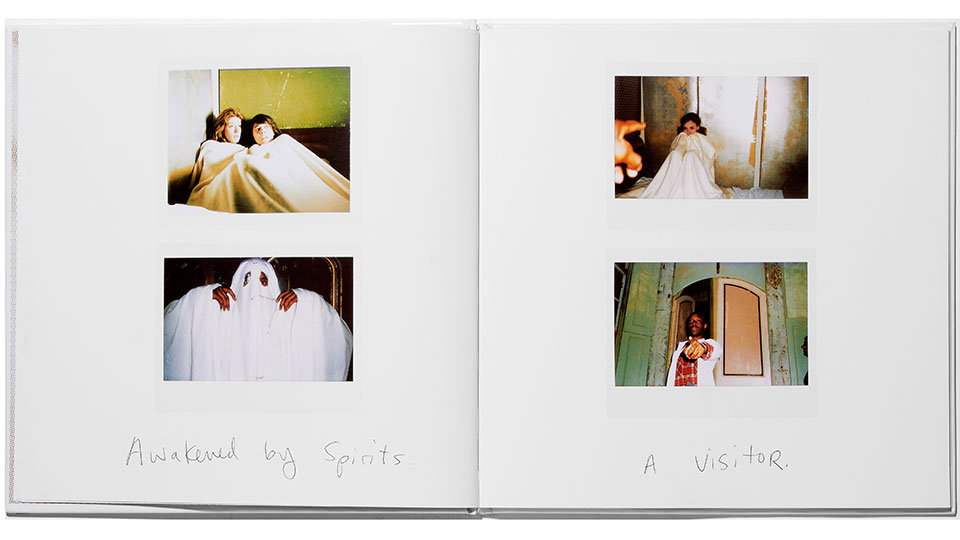

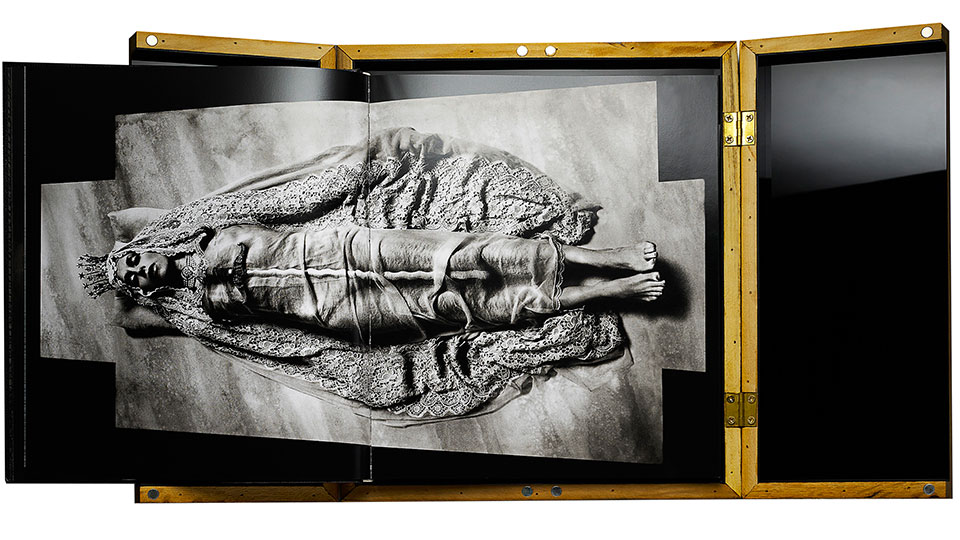

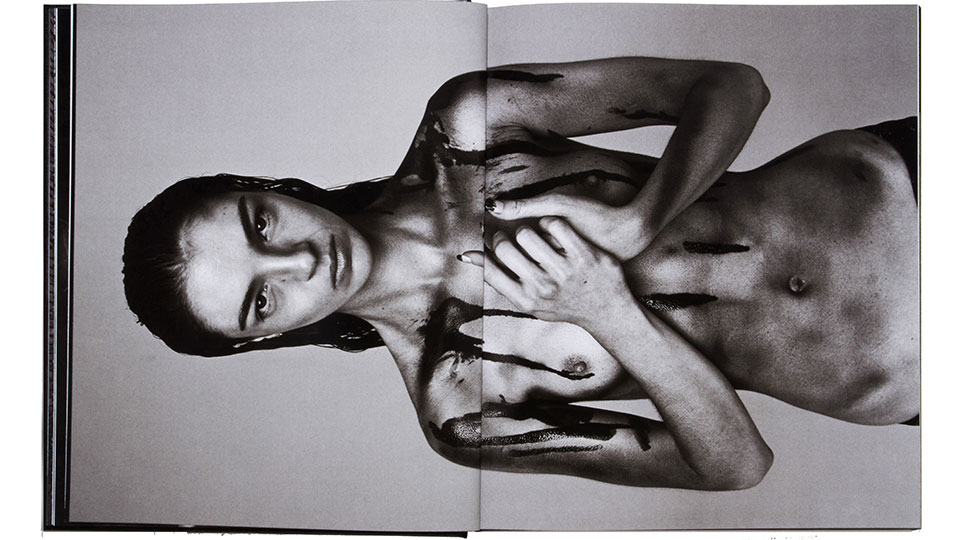

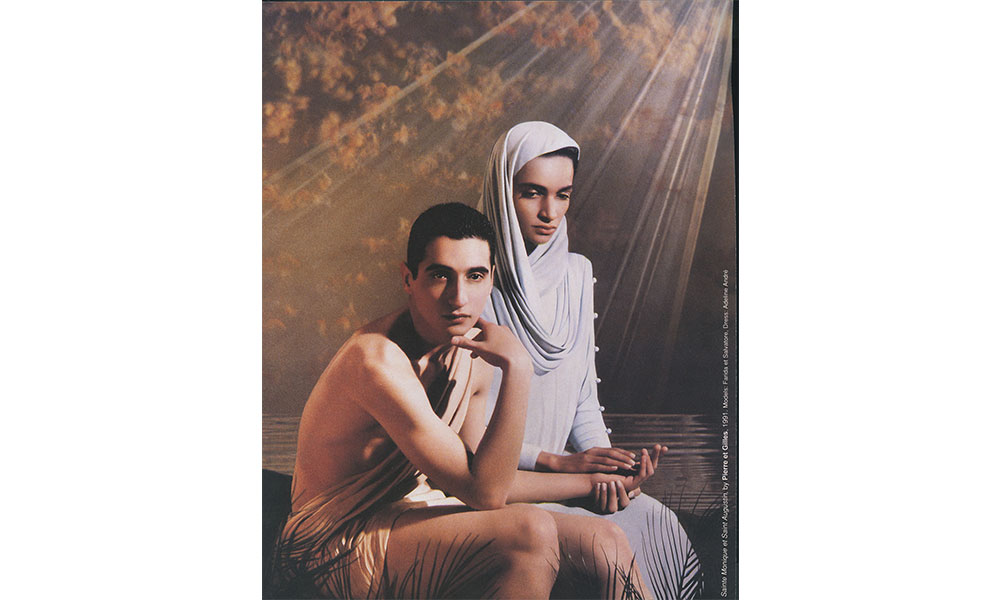

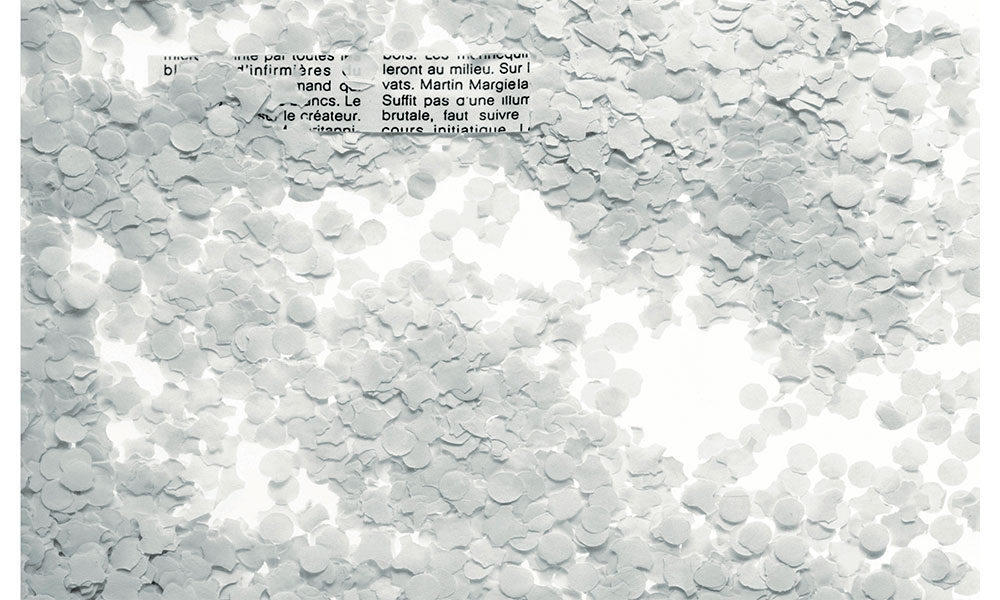

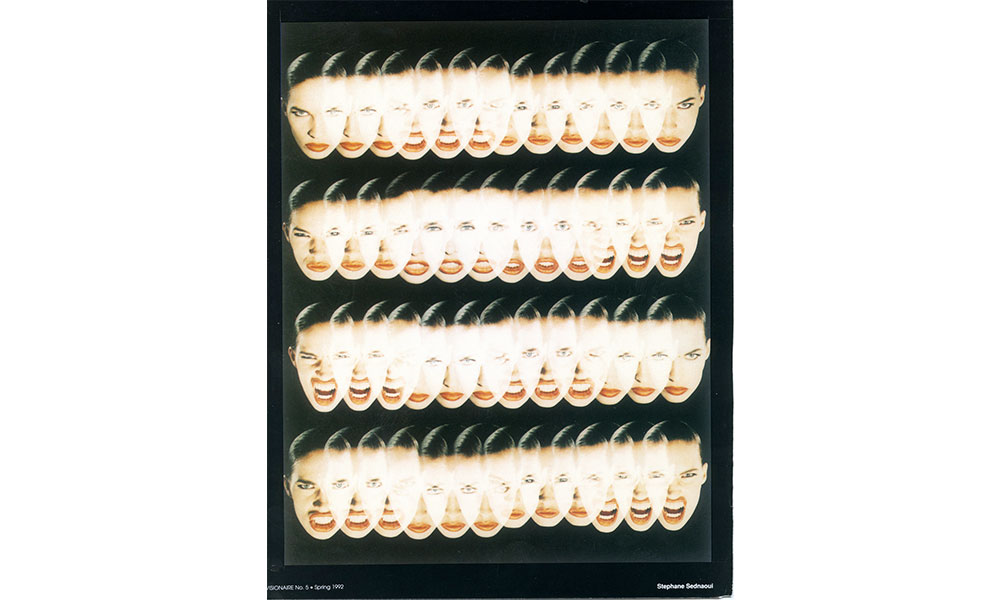

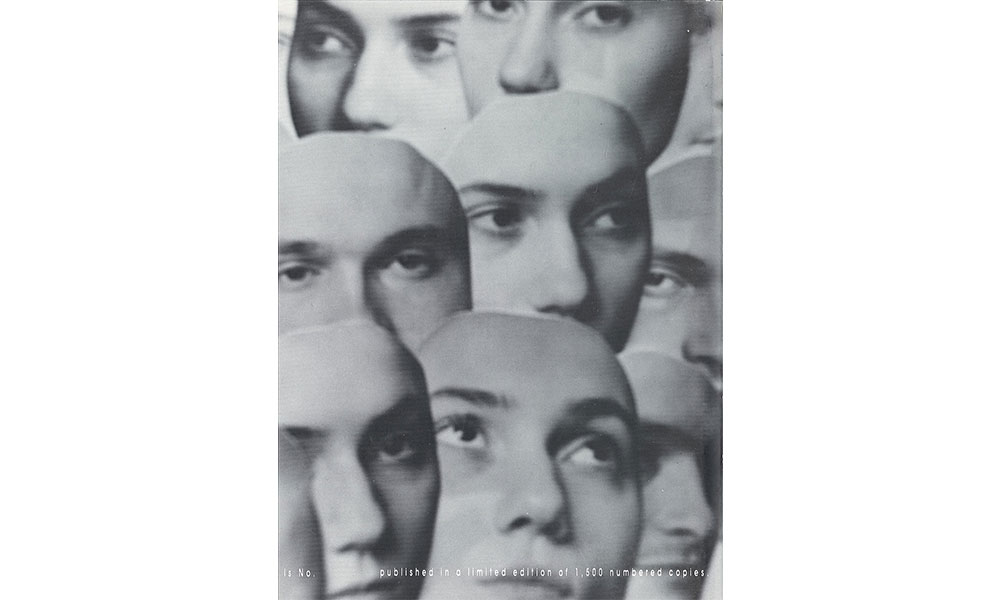

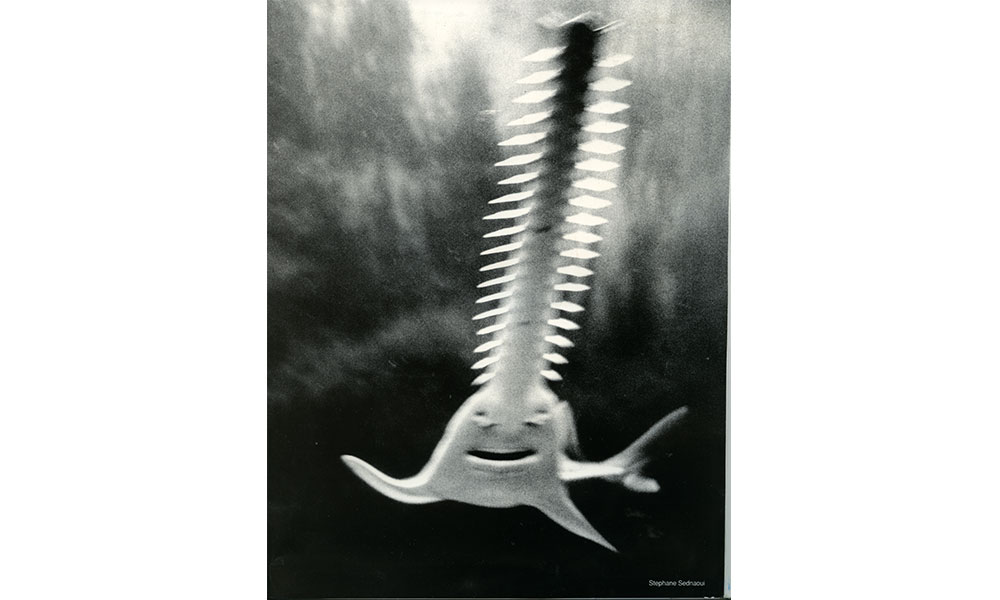

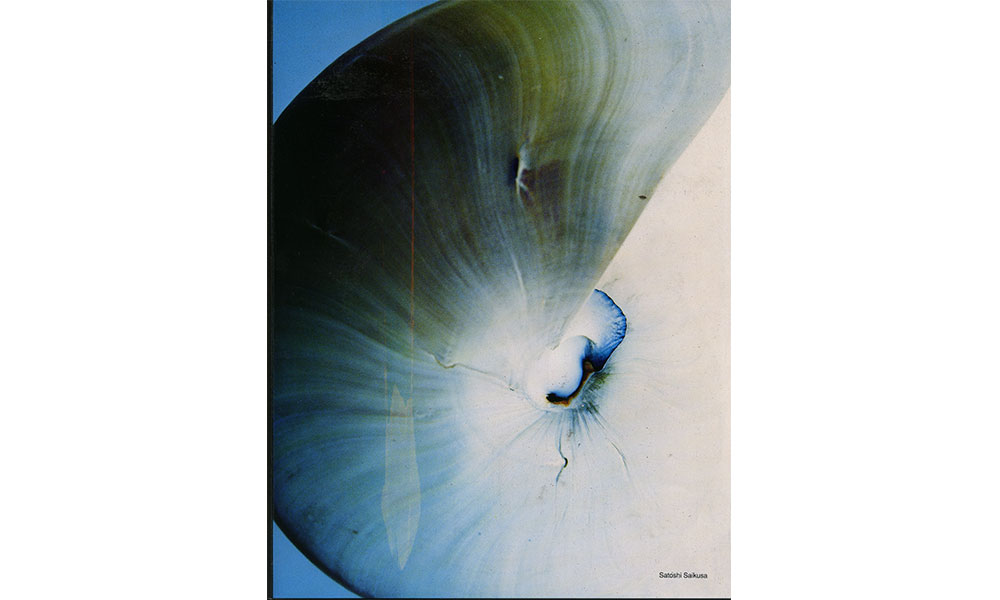

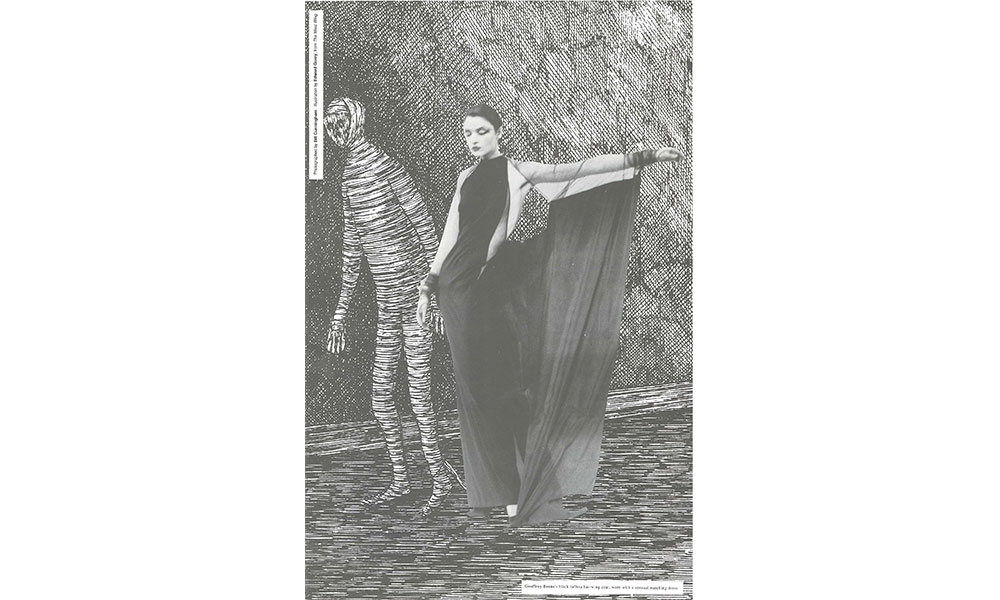

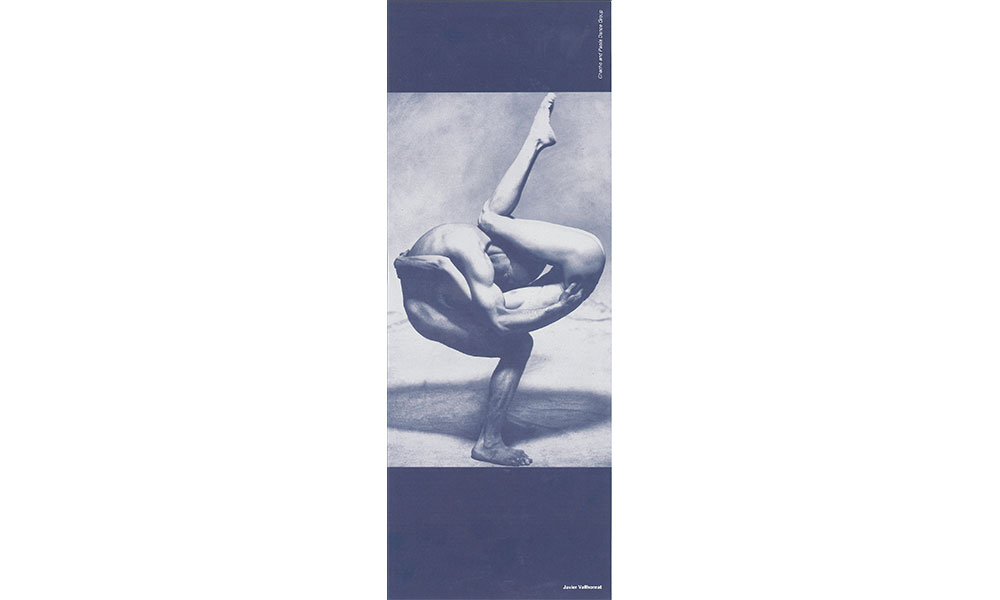

Things that you would hold on to or that you keep referring back to. Visionaire started 25 years ago and we have the same DNA, but it’s evolved alongside the industry’s evolution, and in a funny way, I think it makes more sense now than it did before. Visionaire offers a total experience, and you cannot understand or appreciate it by looking at it online. You have to physically interact with the issues – you have to smell it, taste it, touch it, you have to play a record, you have to take it out into the sun and see it change colours. Plus they’re limited, they’re expensive, so it’s something that people buy and they keep. They share it with friends and have it on their coffee tables. It has a life of its own, instead of being tossed into the recycling bin.

You mentioned that you can’t experience Visionaire online, and at the same time, there’s this idea that the first issue especially was a sort of proto-Instagram. Are these two trains of thought incompatible?

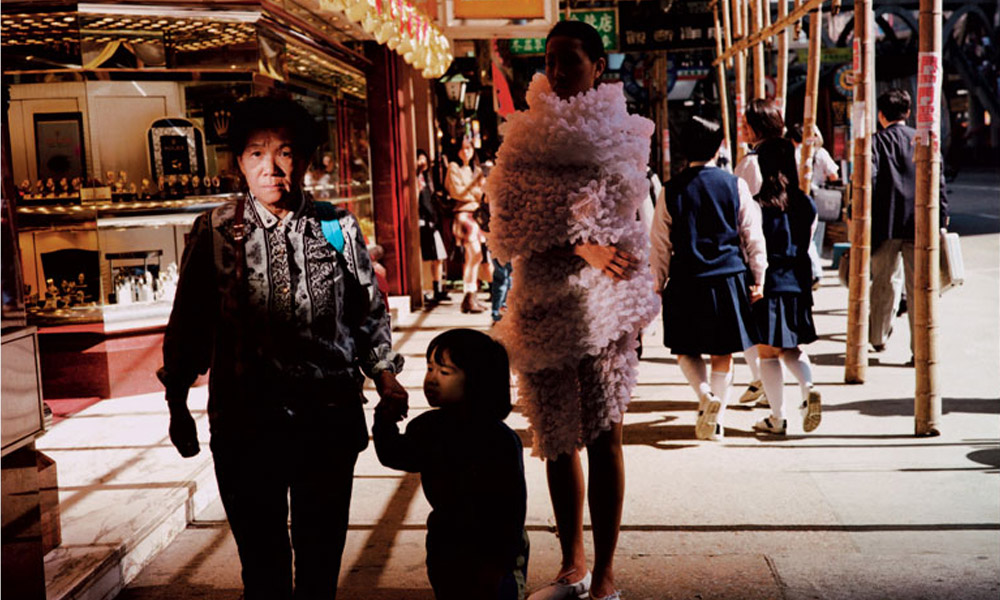

In a funny way, we were kind of like a printed version of Instagram; a place where artists could share images. But, in another sense, we’re the antithesis to online, but in a good way – in a complementary way.

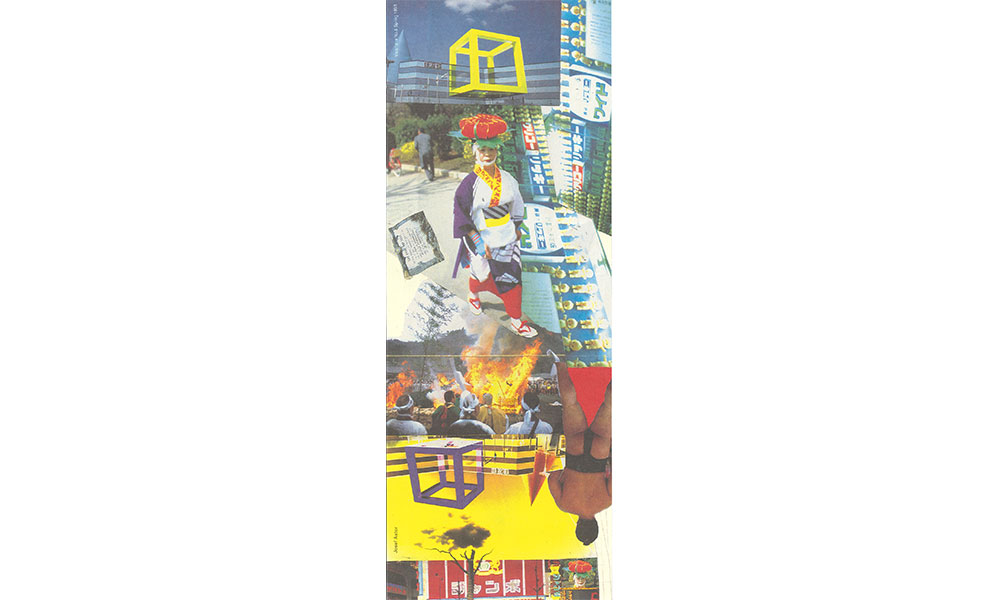

“WE CAME FROM A CULTURE OF LOOKING AT MAGAZINES, TEARING IMAGES OUT AND PUTTING THEM ON THE WALL, SO THAT WAS THE STORY WE TOLD.”

If you were beginning Visionaire now, what do you think the first issue would look like?

If I were like fresh out of school, I wouldn’t start it now; I think I’d probably end up going straight into online or film or TV. You know, starting a business always requires a certain amount of naiveté, and it’s hard for me to put myself back in my head of 25 years ago.

People should start something while they’re in school – whatever tickles them. Start something and you’ll figure it out along the way. I don’t believe in ‘focus groups’ to figure out what is missing ‘in the market place.’ You need to do what you want to do, and if there’s an audience, that audience will appear. And if there’s no audience, that’s okay, you’ve done it for yourself. A lot of people think they need a business plan and investors, and you can’t get into that mindset or you just won’t ever do anything.

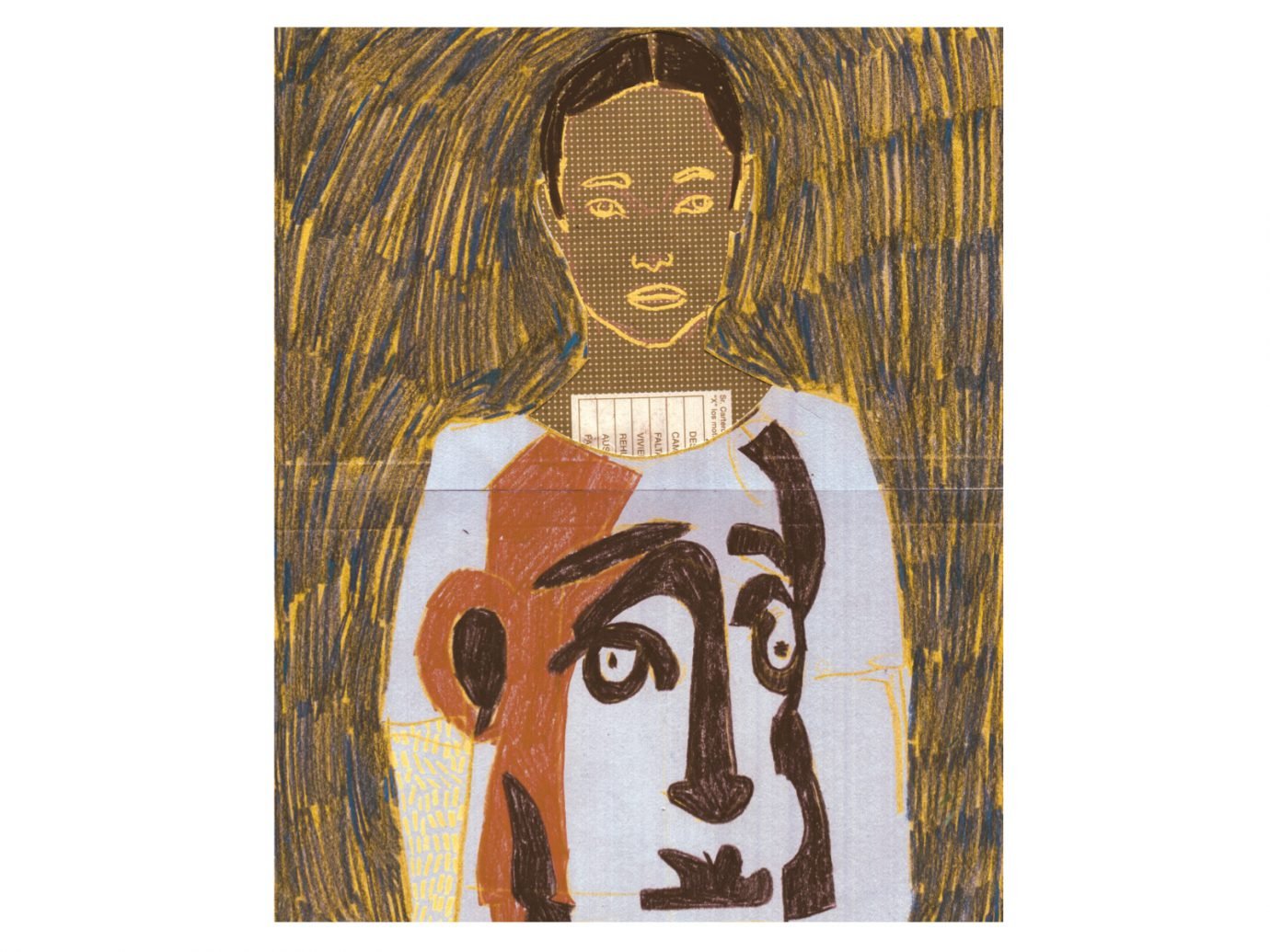

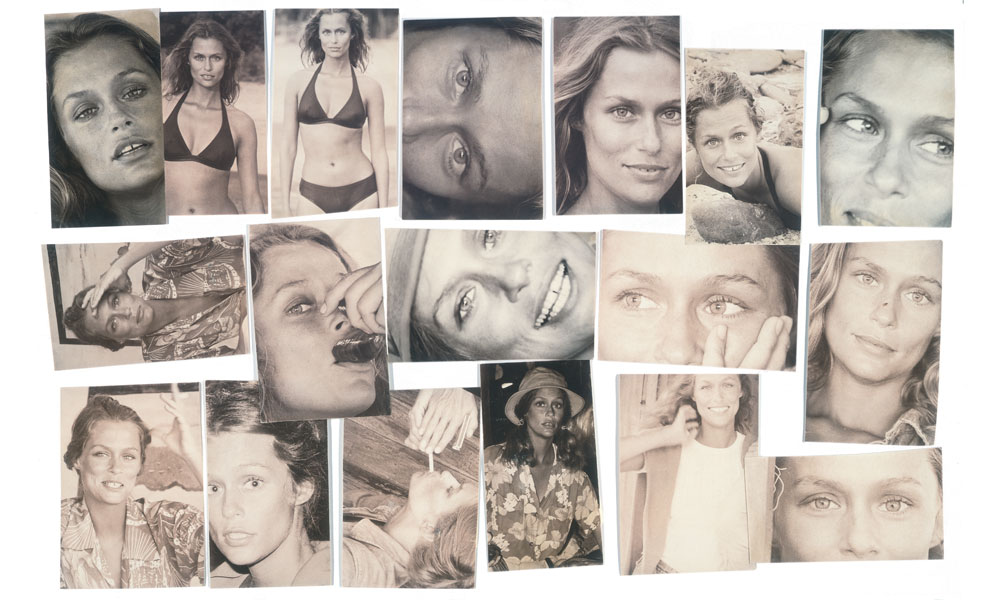

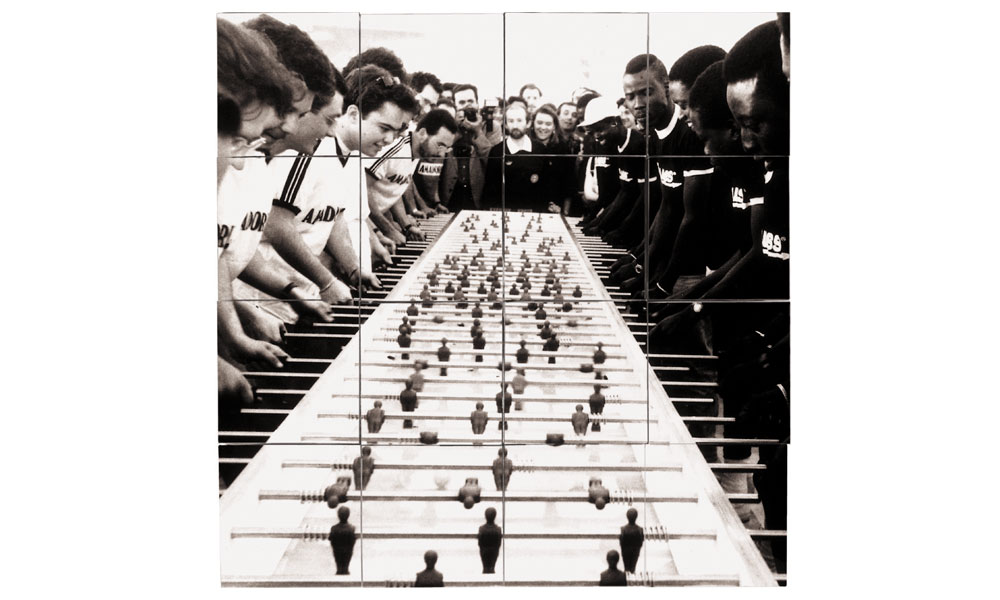

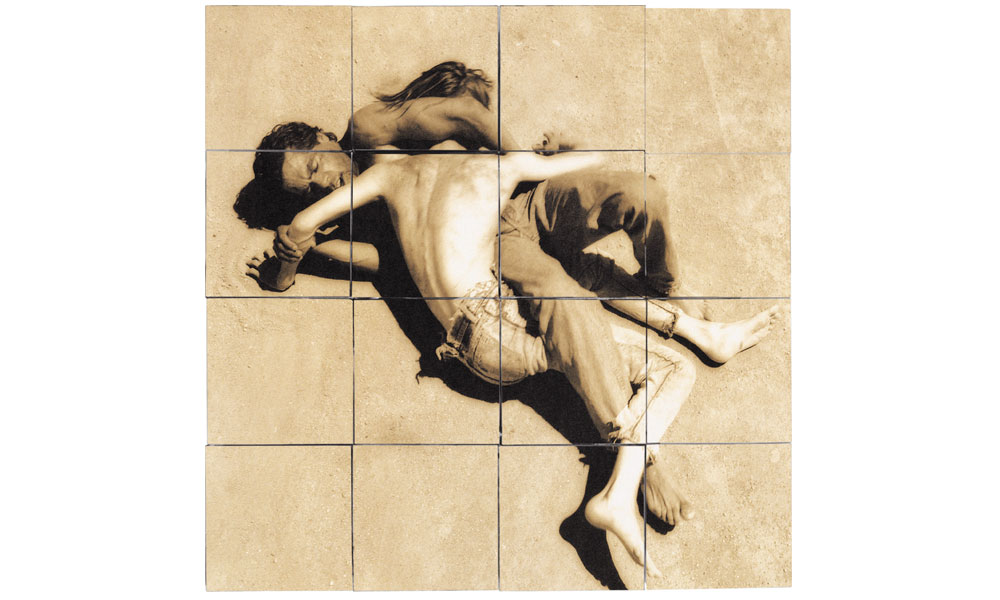

We had no money when we started Visionaire. We went to the printer ourselves, which we found in the Yellow Pages (that’s a printed phone book which probably doesn’t exist anymore), and there was remnant paper that was cheap because they couldn’t use it, so we did. And that’s why the first issue is made from different papers – it wasn’t some grand plan. We were very conscious of what artworks we were going to print on what paper, so it all looked good. And it’s loose partly because we couldn’t afford binding. We came from a culture of looking at magazines, tearing images out and putting them on the wall, so that was the story we told. You have to use all of the challenges and problems and roadblocks as a way to do something even better. There’s always a solution, you just have to find it.

Along those lines, what is some other advice you can share?

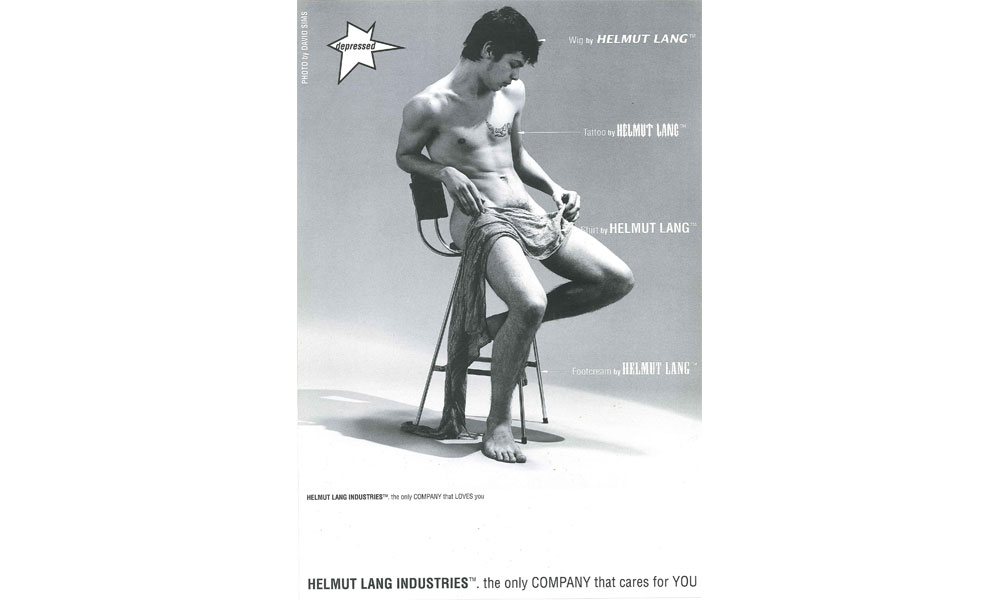

You have to know your history. I love our interns, but we do weekly brainstorms and they’ll suggest a certain artist or format, and we’re like, “That’s so old.” I teach a course at Parsons in publication design and I always tell students to bring in their source material and to not sit in their rooms and try to conjure up a layout. You need to look at things and copy, and eventually, you’ll massage it into your own. But you can’t do it with your peers. So if you want to do a magazine layout, you should not be looking at Vogue and copying that; you should be looking at a medical journal or an Ikea catalogue. Then it becomes interesting. You can talk about whether it works or doesn’t work, but there’s a dialogue to be had, and I think that’s really important to students.

One of my mantras – and I don’t know where it came from but it’s apropos to this generation – is do not e-mail anything that you would not mind being on the front page of The New York Times. I’ve lived by that since e-mail existed. Sometimes I’ll get upset about something and I’ll pound out an e-mail, but then I rewrite it in a constructive way, and I’ll ask myself, “If this were on the cover of The New York Times, how would I feel?” “Okay, I’d stand by it.” If you have to say something negative, you either have a meeting or you pick up the phone.