Monsieur Grumbach, your book ‘History of International Fashion’ is a highly educational account of the evolution of fashion as an industry that can only be understood in relation to the changing social and economic conditions of its times. Why is it important to learn about the history of fashion?

If you want to shape your future, you have to know your past. It is absolutely essential to study the history of fashion in order to be able to position yourself in relation to it.

How did you first get in touch with the fashion industry?

It happened by chance or by accident. When I was 18, I started to work for my grandfather at his coat factory during the summer and the holidays. It was in the mid-fifties and ready-to-wear was still very new. Your great grandmother was not dressed in ready-to-wear, she was dressed in made-to-measure. Coats were the first items to be industrialised, because you didn’t need a fitting as you did for a suit or a dress.

Can you tell me about the beginnings of ready-to-wear and fashion turning into a large-scale industry?

I already started factories that produced ready-to-wear before I co-founded Saint Laurent Rive Gauche in 1966. It was during a period when couturiers like Givenchy, Saint Laurent, Balenciaga, and of course, Chanel, didn’t want to produce ready-to-wear. It was still a very new industry. People reacted to the emergence of ready-to-wear in the same way people first reacted to the Internet when it was new.

People didn’t believe in it.

It was the general opinion that creation and industry don’t go together. People did not believe that ready-to-wear would allow you to be perfectly dressed ; And it was quite understandable since couture and ready-to-wear split, on December 14th 1910, over a hundred years ago and it only happened in France.

For decades, people have foreseen the death of haute couture –and yet it has survived until today. Do you have an explanation for the current revival of couture? Is it an anti-trend to fast fashion?

Again, couture, up to the late fifties, was the only industry. By 1925, there were 300,000 couturières. It was a huge and highly competitive industry. It only became differentiated after the crash in 1929 and in the installation of custom duties and quota when suddenly French couture was not competitive anymore. Couturiers then started to sell rights to copy. Foreign buyers came to buy designs in Paris in order to copy them in their own country. Couture became a ‘bureau de style’ for the world. Paris was the centre of creation. That explains why the brands survived and are still strong today. For instance, Bergdorf Goodman from New York went to Paris to buy designs from Balenciaga, from Yves Saint Laurent etc., in order to reproduce them in their own couture atelier in New York. This is very much forgotten today, but it lasted for a long time up to the moment when Christian Dior, after the war, invented the licensing contract.

It was this business invention that allowed the couturiers to survive?

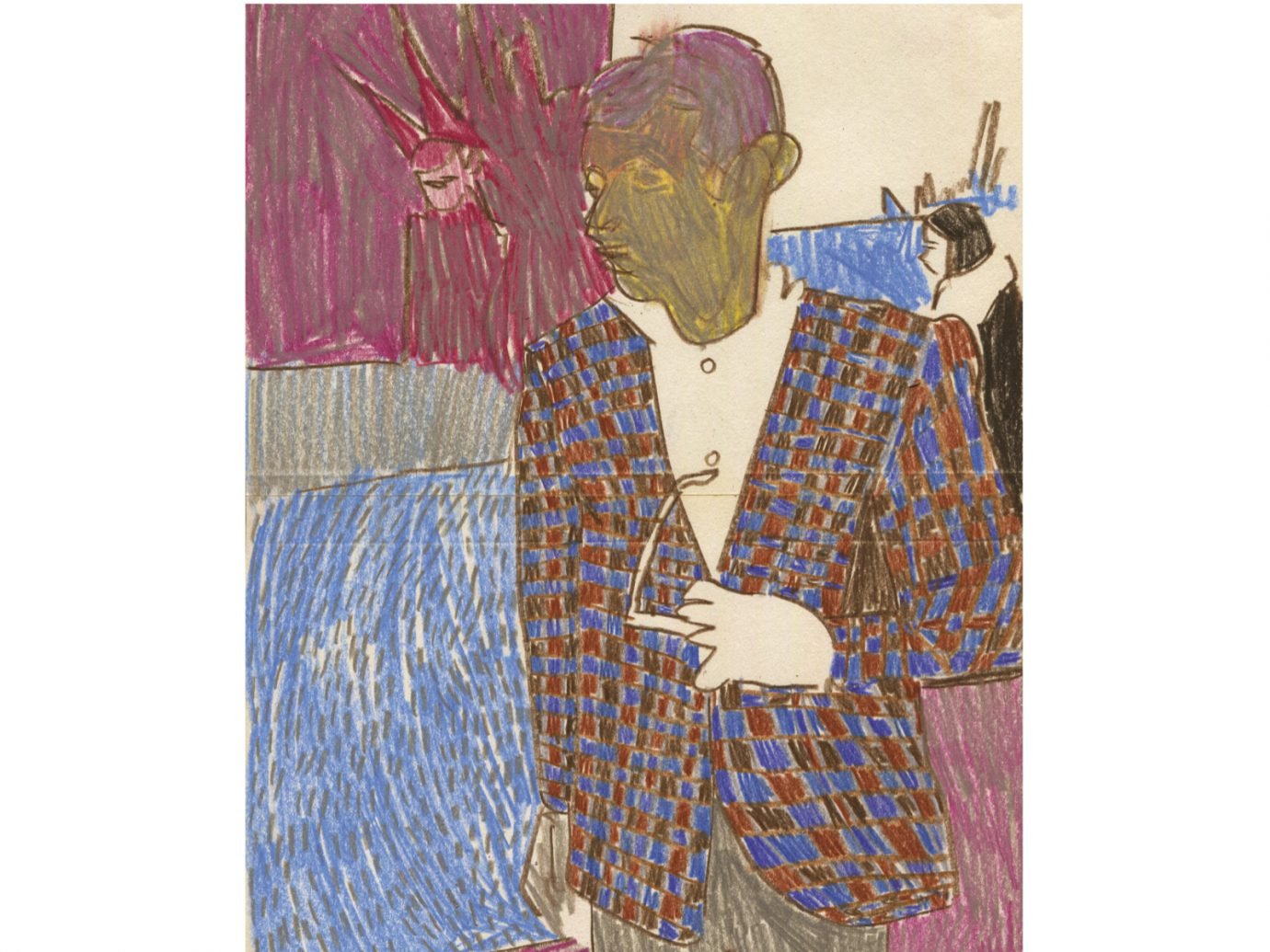

During the war, in the forties, the Germans wanted the haute couture ateliers to be transported to Berlin. This shows how important it was for France to introduce fashion to the world. The Americans had broadly imported French fashion since 1918. Dior was making money by just selling patterns to be copied. The buyers didn’t buy ready-to-wear, but the rights to copy. And if you were going to a showroom you didn’t have the right to take photographs or make sketches, otherwise the police was called. The couturiers didn’t do ready-to-wear, which is something we tend to forget. From 1965 to 1970 the couturiers gradually became involved in ready-to-wear, and a lot of them did it through my grandfather’s company. And, of course, Saint Laurent Rive Gauche was within the Mendès building. The couture house was not involved in the management of production. Production took place in several factories, which I started in 1966 or 1967.

Where were these factories?

In Western France. There is still one in Angers, which is owned by Gucci for Yves Saint Laurent.

I suppose with the beginnings of globalisation, production mostly shifted to other countries.

Up to 1965, production took place in ateliers in Paris. During the seventies, the ateliers became decentralised in province. Licensed manufacturers later started to produce in Asia. But the couturiers themselves, like Givenchy, Ungaro etc., were never involved in the production of ready-to-wear, Courrèges was an exception. They survived by means of issuing licensing contracts. It was through this invention in 1948 that couture turned from a competitive industry into a ‘bureau de style’ of the world, as I already mentioned. Dior first signed a licence to a hosiery manufacturer in America for 10,000 dollars, which was a big sum of money at the time. And when it was renewed a year later it became a royalty payment, and this system evolved until Dior had more than 120 licensing contracts. Saint Laurent and Cardin, who had been assistants of Dior, followed the same system. Licensing, the delocalisation of production and distribution, lasted for 50 years. It finished, as you know, with Chanel starting to integrate production and distribution.