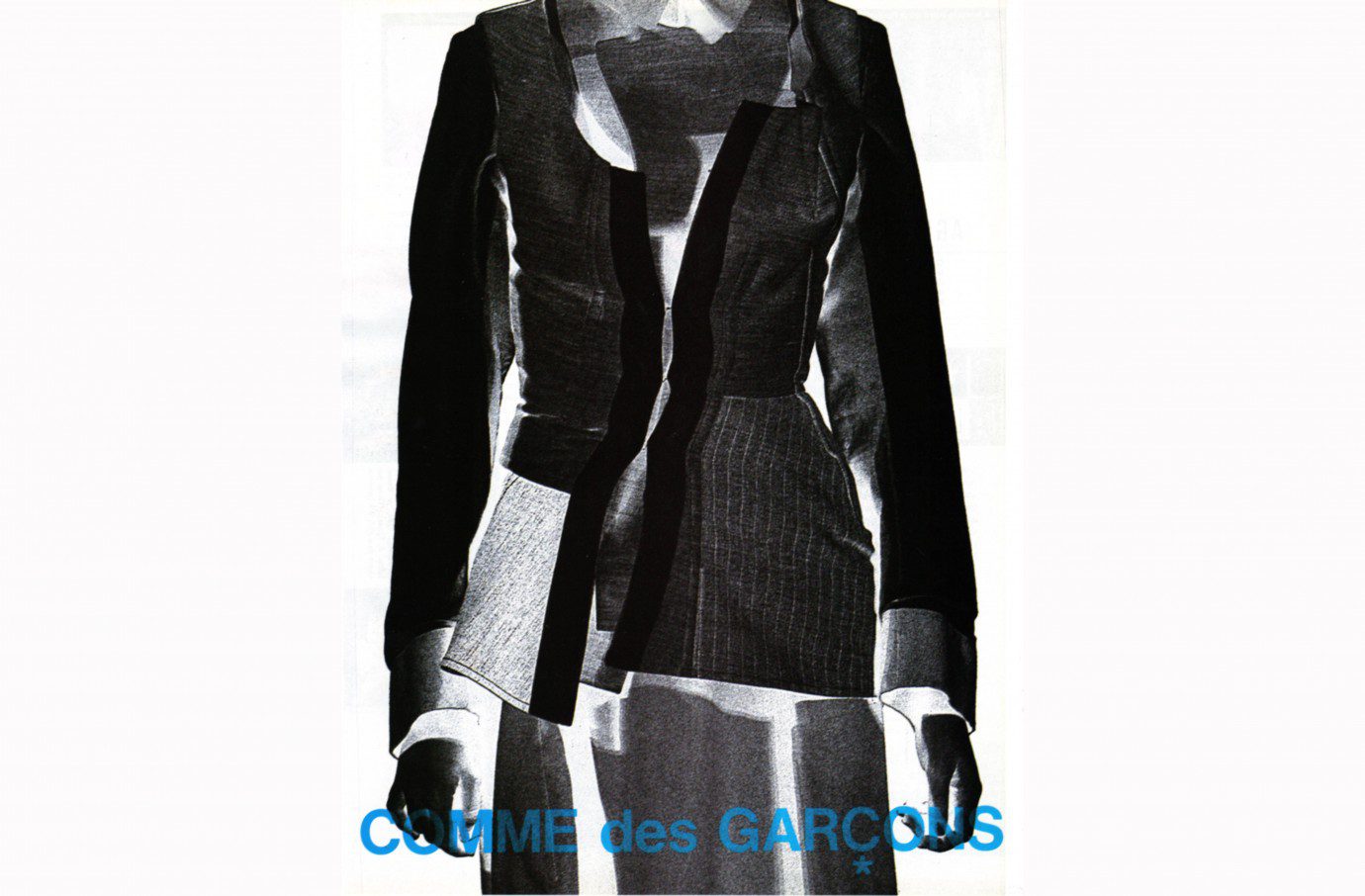

Talking about conservation through imagination, your work has always been surrounded with such strong imagery that there are pieces I know purely through fashion editorials, like the cap dress.

When I started, there was no internet, so the only way to communicate with people was by sending them images. So even from my very early work, the images I kept aren’t from fashion shows, they’re images I had to produce myself to promote and communicate these collections. I think that at that time, more effort was put into the making of those pictures. People were more scrupulous and looking at things in detail. I would buy Italian Vogue and The Face, and they’d stay on my desk for a month. This would be all I had as image food for a month, until the next issue came out. It was very bizarre, because I was always waiting to see more stuff. We weren’t submerged as we are today. I feel lucky that, when I started, some pictures became more iconic than pictures that could be done today, because there was more room for pictures to make their mark. In the exhibition catalog, a lot of the documents are from the early stages, because they feel more interesting. They captured a lot of information for what was about to come.

I’m really curious about how you run your business as well. Did you try to keep it small like when you just started?

I don’t think I could’ve repeated the same thing I did before, the industry has changed too much. When I relaunched, I couldn’t think of a scale that would be appropriate, I just felt like it was important to go step by step, and I wanted to be with people that I could see every day. If that’s your focus, with a little team, you can do a lot. After Theory, it was hard for me to imagine any activity with less than forty people. But after a year off, and focussing on myself, I really wanted to work with a small team where I could have an interaction with everybody all the time, where it feels like a small family. It’s important that those people are very committed and were part of the moment where it all began. We’re still evolving, maybe we’ll reach a bigger number later on. For now, we’re a small team, and I’m working with people that I’ve known for a long time. In the end, when I see the number of people involved on a global scale, it’s a lot. But within the team, my headquarters in Paris, it’s just a handful.

“ON YOUR OWN, YOU WON’T SUCCEED, YOU’LL JUST GET TIRED.”

You left fashion school before completing your degree. What did you learn at LaCambre, and why did you decide to quit?

The first thing I learned, is that there are two threads in a machine. As a child, I was always sewing by hand and I would always look at my mother using the machine. I dreamt about using it, but she’d always take out the spool. So when I’d try in secret, the thread would fly through, but the fabric wouldn’t stay together. So I learned that (at the age of 18!), but it was also my first contact with young people that were creative. I came from a very classic background, a very boring school, I did science and Latin. So I met all these people at LaCambre: gays, eccentrics, designers, and I was fascinated by those other people. Some of them I liked a lot and I remained friends with them.

The first year was fun, the second year I was less concentrated and started working on the side, and by the third year my nature became very strong, and I decided I didn’t want to go to the school anymore. It was very instinctive, I felt, this is enough, so I moved very sudden. I wanted to keep learning on my own. My personality didn’t work, being with other people in a classroom, doing similar stuff, and getting judged by a professor. That wasn’t my nature. I’m not saying it’s better to leave school. But I wanted to remain free from the style education. I was feeling like I didn’t want to be influenced on my style. They did nothing wrong, but that’s what I thought as a 19-year-old kid. I wanted to remain white and blank from the point of view of others, and do what I believed in. When I just left school, I had drawn my first collection, SS98, and I had no point of view on it. I left school with nothing but my collection in mind.

I tried to do internships, at Jean-Paul Gaultier for example, I arrived with my sketches and the lady at the reception said: “You can leave them here, we’ll call you back.” And I thought: “I can’t leave them here, it’s full of ideas!” So I just left and decided to do my own thing.

Starting your own label right after school, what was your biggest challenge back then?

Everything was happening very organically. The challenge for me was that the industry requires of labels or brands to have enough organization, to ensure that they can produce and deliver. At my early stages, I was struggling to find the best, or the less bad, scenario to be able to produce. The first year, I just presented what I was doing to buyers and press, but I wasn’t able to actually produce it. I told them we had to wait a season. I was very cautious not to spend too much, I was using material from back home, like old linen sheets and lace from my family. I think that, at that time, buyers were more open and used to the fact that a new designer would be a bit late, and that there would be imperfections. There was a level of tolerance, that nowadays is gone. There are fewer people in the field that have this capacity to cope with imperfections. I wasn’t perfect when I started, but it didn’t hurt my business back then. I also had a lot of support from important actors in the field that helped me with the commercial part. So my biggest challenge was definitely to get organized, and I also think it’s where most young designers fail. I had a lot of help from people around me, a friend from business school for example. You should always look around you and think about who could be able to help. That’s important, not to stay in your own little cell. You have to share what you want to do, and consider teaming up. On your own, you won’t succeed, you’ll just get tired. You also need to understand that a big part of the job has nothing to do with designing, you’re faced with practical situations and paying bills. On that side, you can’t make any mistakes. If you’re not organized, your business will fail.

You also had a lot of press attention from the start, and a few celebrity endorsements. How important was that to you?

I think that it was important, but that it isn’t today anymore. Everybody sees so much media, and receives so much information. If we transport ourselves back into the 90s, where we had to communicate by fax and meet people to show your clothes, back then, having the support of someone like Isabella Blow, who put a silhouette on the cover of the Sunday Times… It was something people in the industry would pay attention to, and they would show up to the presentation or the showroom. But that whole thing, I don’t think it happens anymore today. Back then, there was a small number of professionals who really had an impact on the industry, whether they were buyers or journalists. I’m not convinced that is still the case today.

You have sat on the jury for schools a few times. Do you ever see students like you, who don’t need education to develop their style? Or is it very rare?

It’s hard for me to tell. I think there are people who have the talent to spot other talent. When I meet students during jury time, they’re usually not in their natural state of mind. So I don’t really think about it, and I don’t know enough about it to be a specialist. When I had my first publication, a small picture in The Face magazine, I was instantly contacted by a guy from Italy, a talent scout. He had been behind the beginnings of McQueen, and many other Belgians like Ann Demeulemeester and Dries Van Noten. He would put young designers in touch with manufacturers, and he really helped me to get there. He taught me where to be cautious, and what steps to take. It was really crucial for me to have him at my side, someone who could spot talent, but also knew the industry. His experience was very important to me. I’m still thankful for his guidance. It’s impossible to leave school and immediately have all the keys to understand how to maneuver through the industry. You need advice from people with experience.

I have one last question. Talking to you, I have the feeling that your education didn’t stop after you left school. For example, you mention learning to make the perfect tailored jacket at Theory. At what point did you feel in control of your creative expression?

I think it’s different. There’s never a moment where you reach the final level and just stay there forever. That’s not what happens. Sometimes you might reach it, but then a year later, because you start moving onto something else, you come back down to the learning. I can recognize that there were points at Rochas, for example, where I was really on top of my game. I don’t think I was ever at a place where I felt like I couldn’t learn anymore. That just isn’t my personality, other people might be like that but it would be boring for me, I wouldn’t like that. With the relaunch of the label, I started working on my own classics, and I’m flirting with the feeling of already having done something. I know that with my personality, I’m always moving on to something else. I think that’s what life’s about, you get bored if you don’t try something else.