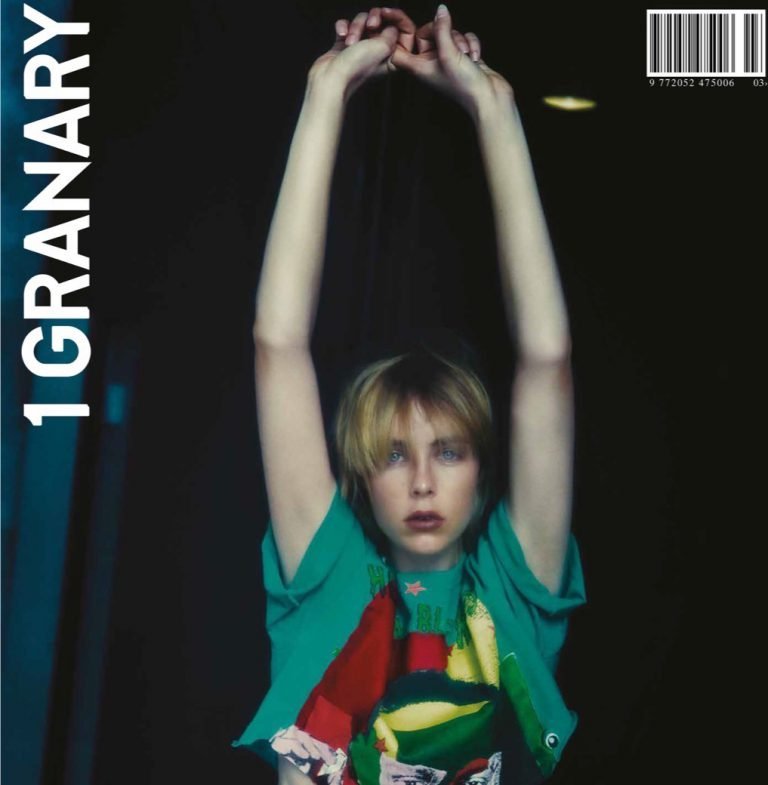

Edie Campbell, wearing archive pieces of Meadham Kirchhoff. Photography by Drew Jarrett, styling by Anders Sølvsten Thomsen.

“YOU HAVE TO KEEP IN MIND THAT YOU ONLY HAVE 60 SECONDS, AND YOU WORK TOWARDS THIS MOMENT FOR A YEAR.” – TIGRAN AVETISYAN

“YOU CANNOT CALL YOURSELF A CONTEMPORARY DESIGNER WITHOUT CONSIDERING THE WORLD AROUND YOU. HAVE SOME FUCKING DIGNITY. MAKE A DIFFERENCE.” – RICHARD MALONE

“YOUNG DESIGNERS OFTEN TRY TO CRAM IN A THOUSAND IDEAS WHEN THERE IS JUST ABOUT ONE IDEA THAT IS GENIUS.” – NICOMEDE TALAVERA

“GALLERIES ARE AS ANXIOUS ABOUT MISSING THE BOAT AS YOU ARE.” – RICHARD DEACON

“IF THERE WERE PAINTINGS HE FELT WERE NOT WORKING HE’D DESTROY THEM. HE WAS TOUGH ON HIMSELF.” – DAVID DAWSON ONLUCIAN FREUD

“I HATE IT WHEN THINGS LOOK FORCED, LIKE A STILL FROM A MOVIE. IT HAS TO FEEL NATURAL.” – LOTTA VOLKOVA

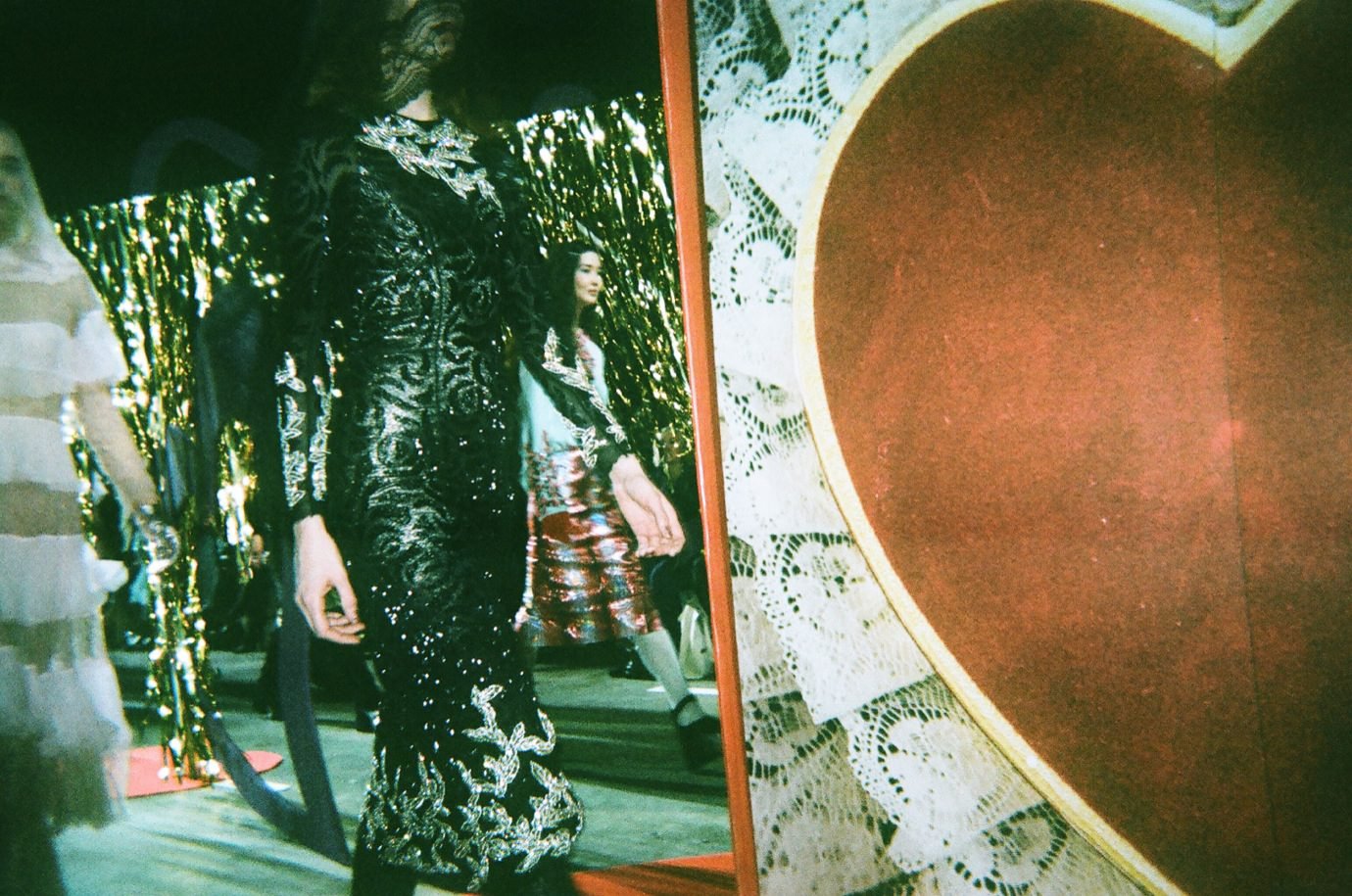

“WE DIDN’T FAIL BECAUSE WE’RE SO UN-COMMERCIAL; WE ARE NOT A VICTIM OF THE FASHION INDUSTRY.” – MEADHAM KIRCHHOFF

“[LOUISE WILSON] SAID TO ME, “YOU GREW UP KNOWING WHERE A CHAIR IN A ROOM SHOULD BE – YOU NEED TO STOP THINKING ABOUT THAT FOR A MINUTE AND GO AND LOOK AT SOME PORN!” – SIMONE ROCHA

“THERE’S SOMETHING ATTRACTIVE ABOUT BEING CONSTANTLY POSITIVE ABOUT THE POTENTIAL OF THE NOT SO DISTANT FUTURE.” – THOMAS TAIT

“THE BUSINESSMAN CAN’T BE REALLY SUCCESSFUL UNLESS HE TRUSTS THE VISION OF THE DESIGNER.” – ADRIAN JOFFE

“THE MARKET IS CROWDED. CREATING ANOTHER LINE OF CLOTHES JUST BECAUSE DESIGNERS WANT TO PUT THEIR NAME ON IT IS NOT GOING TO WORK.” – ANDREW ROSEN

“I THINK THAT THERE IS NO EITHER YOU ARE A CREATIVE PERSON OR A BUSINESS PERSON: TODAY YOU NEED A CREATIVE THINKING MINDSET.” – FLORIANE DE SAINT PIERRE

“YOU SHOULDN’T BE TAKING MONEY FROM PEOPLE WITHOUT UNDERSTANDING WHAT THEIR EXPECTATIONS ARE.” – HUGH DEVLIN

Team Letter

The people we have asked to be featured in this issue have one thing in common: a need to question and challenge the increasingly destructive system we’re in. It’s essentially problem-solving in various forms, whether it’s identifying the gaps in the arts education system or the many obstacles that young designers and creatives are facing while trying to start small businesses.

Nobody more so than students have faced systematic injustice in the last few years. Never before has there been a time in which graduate unemployment was this high. Today, nearly half of recent graduates are in non-graduate roles within retail or office admin. The Guardian recently uncovered that the proportion of graduates failing to pay back student loans is increasing at such a rate that the Treasury is approaching the point at which it will get a ‘zero financial reward’ from the government’s decision to triple tuition fees to £9,000. If you think that’s bad enough, it’s only going to get worse.

It’s not just in London, either. But luckily, all around the world, plans of action are being put into place to help wriggle our way out of an out-dated system that is neither sustainable nor ethical. One of the ways in which we can begin to approach the problem is by considering it semantically. By sustainability, we don’t just mean improving things for the greater good of the ecosystem (although go ahead, by all means) but in terms of the environments of the industry in which millions of people work, study and aspire to be a part of. Everywhere from education to production to consumption, new ways of approaching sustainability should be on the agenda from the very beginning.

Did you know that there are 8,000 womenswear design students alone who graduate in the UK every year? Do they know there’s not a fraction of those jobs out there for them? And for those who want to start their own label, how many of them do you think have been taught about the business, the copious capabilities and economies of production or even just how they can develop new ideas in terms of business and communication that extend beyond aesthetic design and fabrication?

Beyond fashion design graduates, how many of those working within the industry are aware of the fact that the fashion industry, as only a piece of the complete system of production of commodities, is deeply unsustainable? It may be the relentless working hours without any pay for students; the 80-hour workweeks in a row without any days off whilst being deprived of their creativity as their employers produce more collections each year, transforming the design industry into an assembly line? Why is there so much pressure to stay in that established system and say nothing? Simultaneously, with the increase of speed and output, why does the quality of high-end products worsen every year?

We’re talking about the industry that is not only the second biggest polluter in the world after the oil industry, but is also causing the highest rates of mass suicides. 270,000 Indian cotton farmers have killed themselves in the past two decades, as documented in The True Cost, the highly important recent film by Andrew Morgan, which uncovers the many diseases present in our system and shows the serious implications of globalised capitalism that only benefits the few. Our economic system only measures in ‘value’ that which is traded, not a human economy or natural economy of the earth. Yes, we all know that fashion is a whopping £1.2 trillion industry (respectively worth £350 bn and £26 bn to US and UK) but after finding out how much of that money is due to poor treatment of human and material resources, it quickly sours and becomes rather disgusting.

Perhaps the answer lies in the generosity of those luxury giants and institutions investing their capital back into the schools and emerging talent that follow after them. Certainly the reinvestment of capital into funding small businesses, investing in scholarships and, less monetarily, providing young people with mentorship and opportunities to collaborate is what’s most important. A number of brands have already taken suit — from LVMH and their generous annual prize to the BFC’s recently announced Louise Wilson Memorial Fund. In working on this issue, we were astounded by the number of esteemed professionals who gave their time to working with us in the spirit of supporting young people and creatives. In doing so they gave us something much more valuable than money: skills and mentorship.

Change is already being made close to home in art colleges around the world. With Burak Cakmak, a catalyst for sustainable change in many high luxury houses, being appointed as Parsons’ new Dean this year, as well as the appointment of Zowie Broach, who notably urges her students to think outside of the established system, as the Head of Fashion at Royal College of Art, there remains optimism for the future. But, that’s not enough. As Burak Cakmak told us, only an evolution can happen within the established fashion houses, so it’s up to our generation to take the lead and revolutionise.