You’ve said this project began with a stack of misprints – things most would consider mistakes. What made you want to hold onto them in the first place?

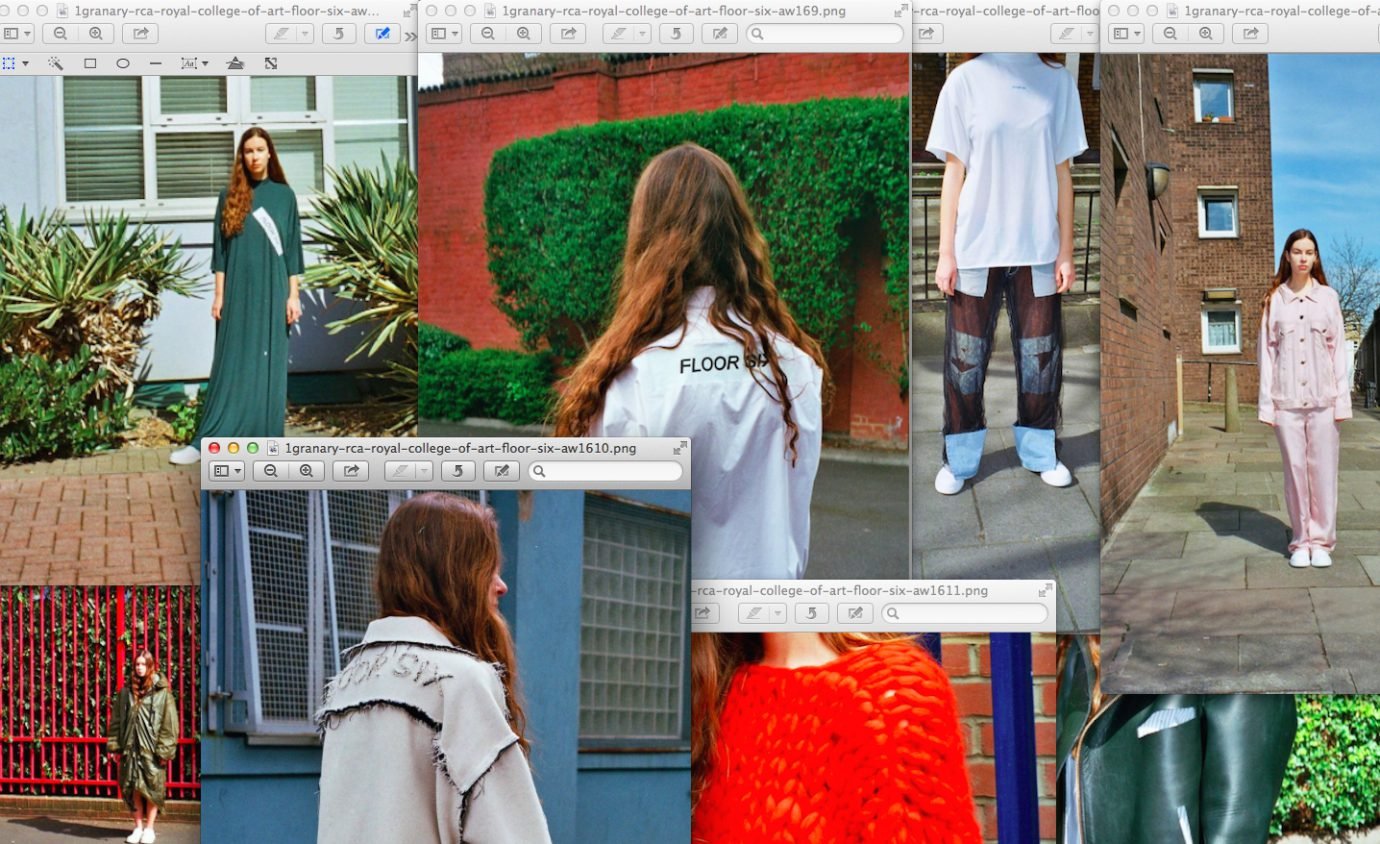

I’ve always believed that the process is just as important, if not more, than the final result. There’s something deeply compelling about witnessing the in-between moments, the rawness of creation. At the time, those misprints felt like part of a larger, unintended choreography. I was lucky to have kept them. They revealed this mechanical poetry – images that didn’t belong together, suddenly colliding into something unexpectedly beautiful. I wasn’t always a fan of imperfection, but I’ve learned to embrace it. It gives me freedom, and with that comes a certain vulnerability. That lack of total control makes the process more alive, more emotional, even more human. It’s different from design, which often prioritises outcomes. This was more like a drip of paint falling where it may. That’s what I find thrilling.

There’s something radical in turning discarded material into the centre of a collaboration. What did that shift – from error to artefact – unlock for you creatively?

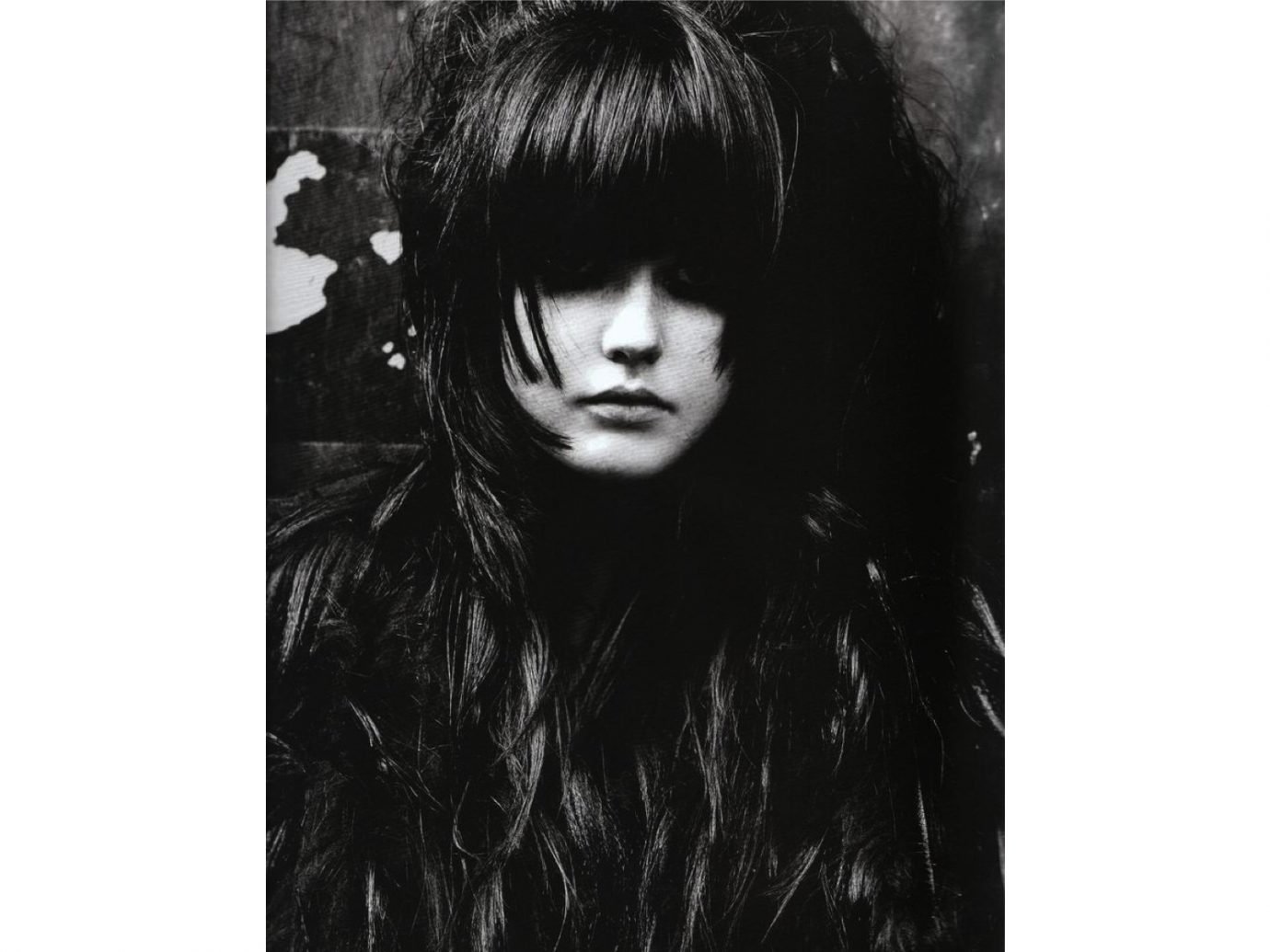

It opened up a space for interruption, an interlude, even in the traditional magazine-making process. I didn’t want it to follow a professional or journalistic formula. I wanted the features to breathe, to speak for themselves without over-direction. It was about giving artists and collaborators the freedom to respond visually, intuitively, without rules. The idea was to invite something raw – a kind of primal scream between the contributors and the material. That shift turned the so-called ‘error’ into a space for dialogue, and for me, that’s where the magic happens.

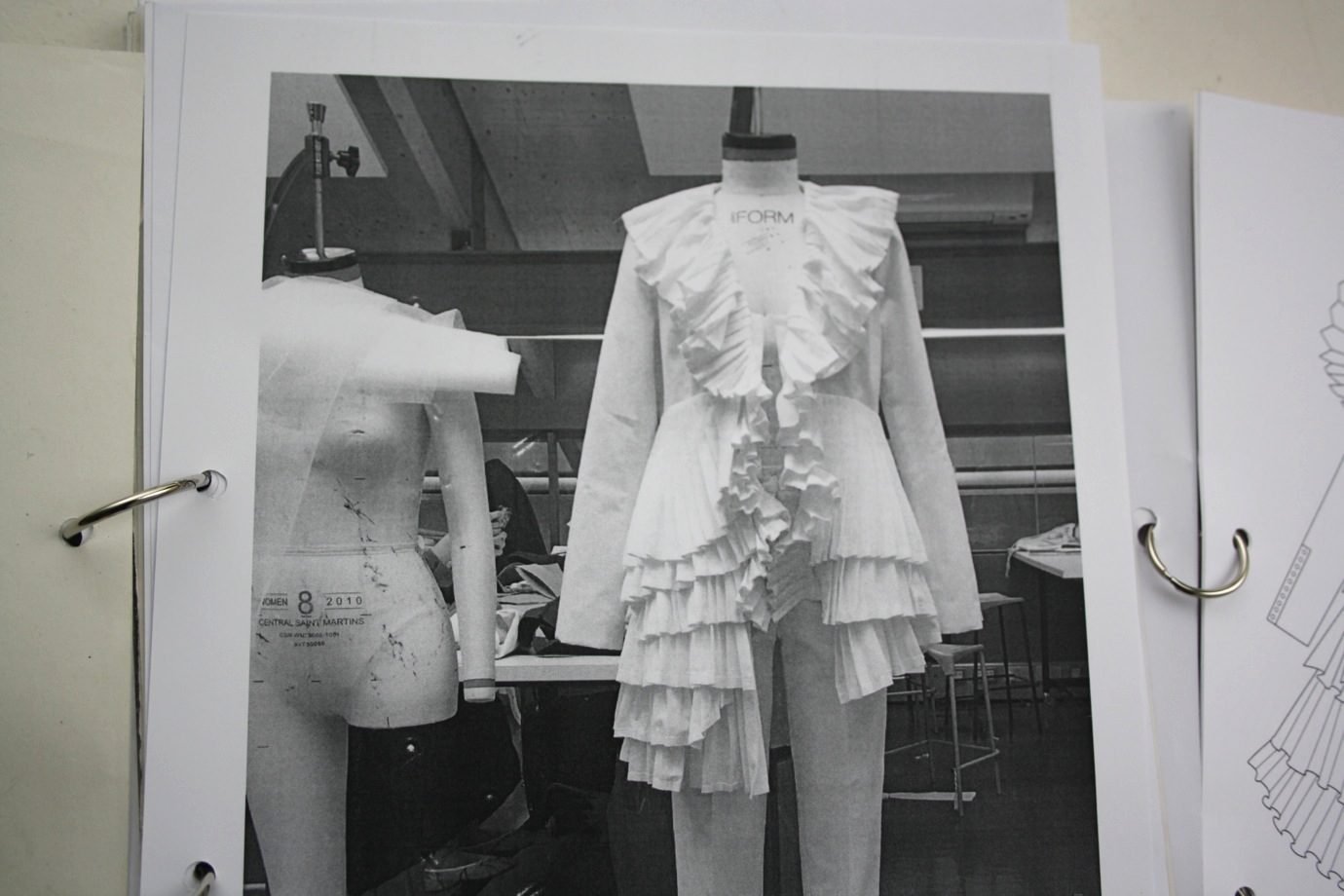

Did working with Jun Takahashi, who’s also known for disrupting conventions, change how you viewed the archive? Or what it could become?

I’ve always admired Jun’s punk sensibility – there’s such a rebellious energy in his work that resonated with the ethos of Modern Matter. The magazine itself is rooted in that DIY attitude. There’s no rigid structure, only curiosity. Jun’s own artistic practice – his painting, his embrace of mistakes, his ability to reconstruct and reinterpret – mirrored a lot of what I was trying to explore. It felt like a natural fit. Even in the design, I used a large “U” on the cover as a nod to both of us, JUN and OLU – almost like a shared initial, a visual acknowledgement of our connection within this project.

So many young creatives are obsessed with making something ‘perfect’ for fear of being misunderstood. What role has failure played in your own creative evolution?

Failure has been essential. It’s in the moments where things fall apart that the most interesting ideas can surface. When you aim for perfection, you often land somewhere safe – and honestly, safe can be quite boring. I always tell young creatives: your work is evolving. Just because it doesn’t look “perfect” now doesn’t mean it isn’t valid. You might just be in an early phase of something extraordinary. Perfection, to me, is commercial. It’s the process – the mistakes, the mess, the risk – that holds the real excitement.