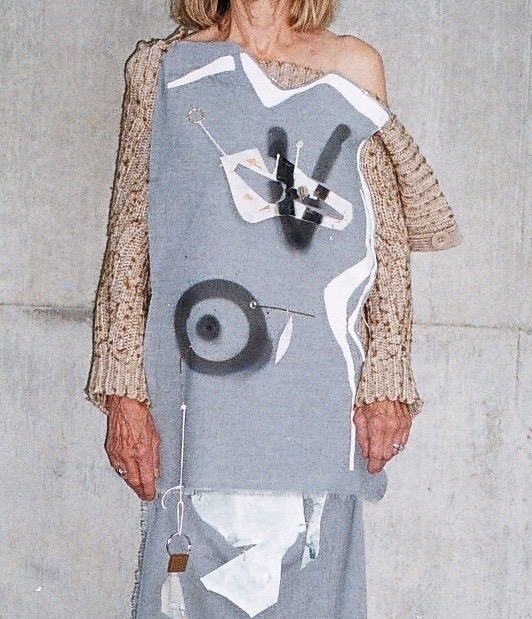

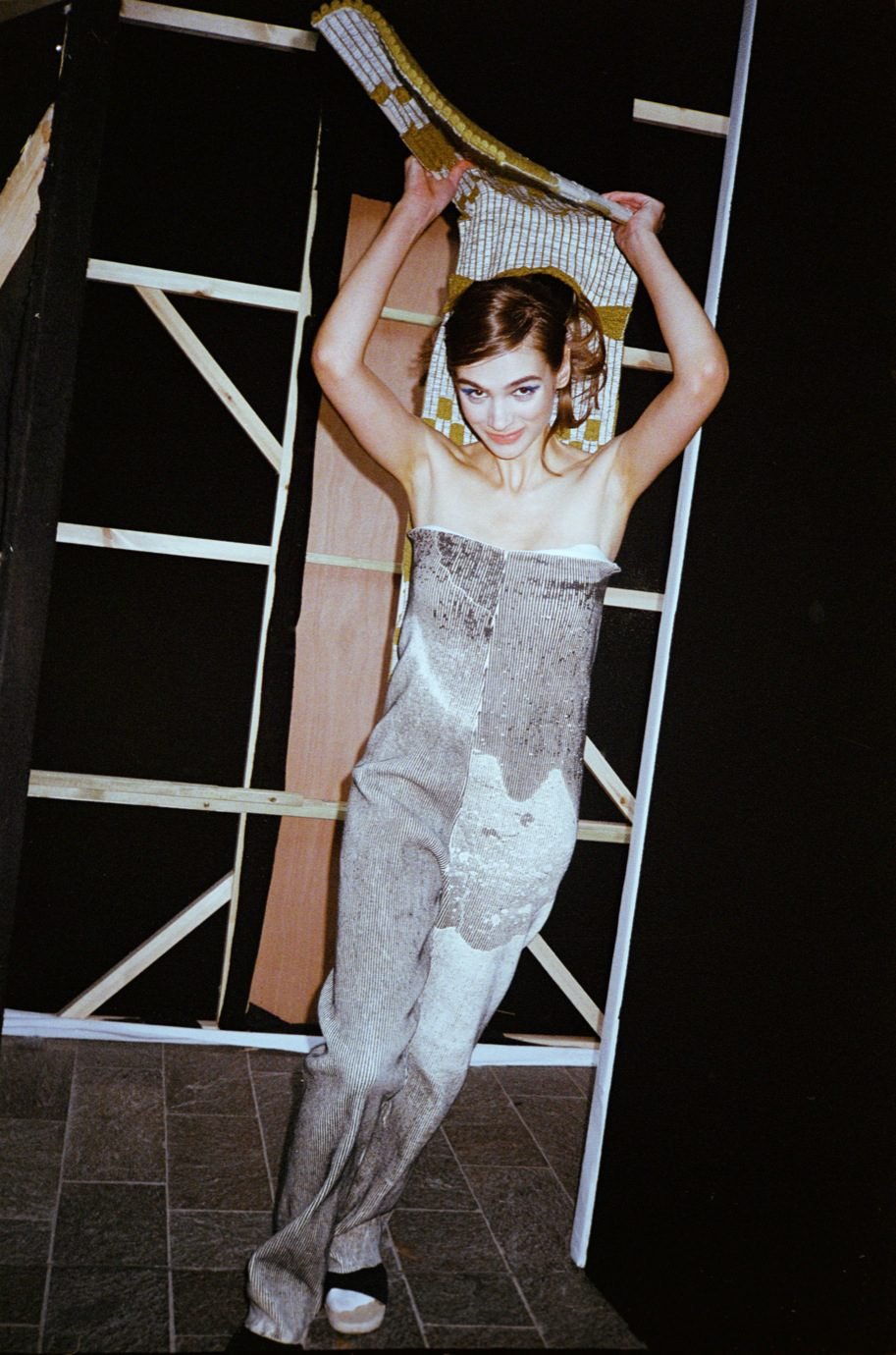

“I needed to be completely honest and realise an underlying fear about my own body. Through this I realised that a fear I had as a woman was how I felt such a numbing pressure to accomplish so much before I have a family, because then my career or goals might have to be shifted to one side, or at least interrupted. I also felt such a pressure to enjoy my body whilst I was young, because I saw so many women around me yearn for it and try to recreate it after childbirth or as age increases. I felt my body was biologically a ticking time bomb, and I knew a lot of women who felt the same.”

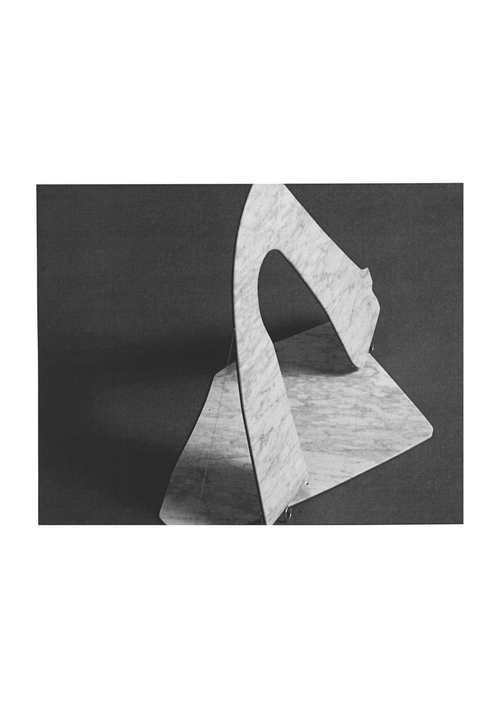

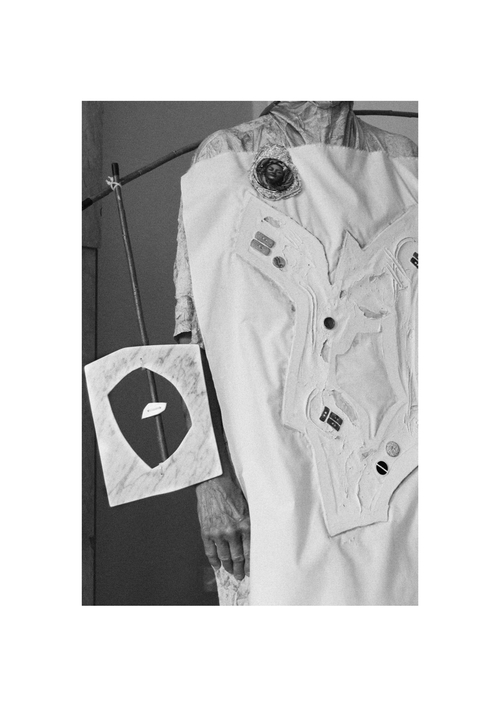

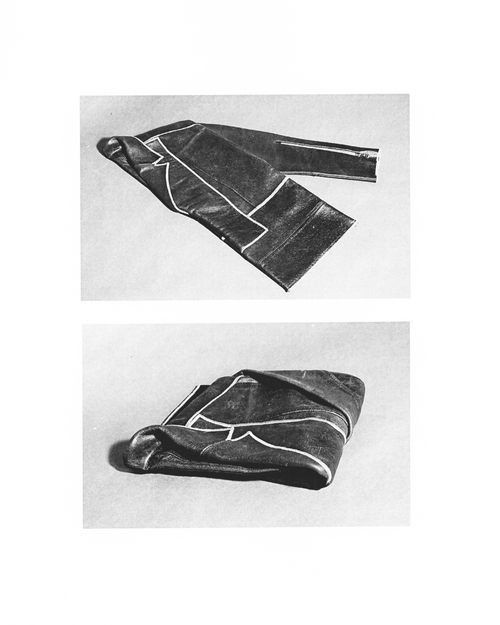

The fear of ageing is very often accompanied by questions of identity. This is mainly because it is a silent cultural statement that when a female loses the attractiveness of the youth she also loses her function in society. Such function appears, at least in an implicit way, linked to reproduction. Grace explains the statuesque scenery of her designs as “if a marble sculpture were exploding” —an ideal female marble figure in the moment of collapse. “Fracturing” and “unpackaging” are two empowering activities of deconstruction (as well as of unlearning) which were essential in her creative process. From the fracture that comes from the dismantling of the ideal of youth, explains Grace, the flesh emerges as “brutal nature” an idea that she translates as “being a completely honest body, which gladly faces reality”.

¨I DON’T BELIEVE IT’S ENOUGH TO JUST KNOW WHAT BEAUTY IS AND GO FROM THERE, I THINK IT IS STILL NECESSARY TO DIG TO THE ROOT TO REALLY FIND WHAT BEAUTY MEANS AND REPRESENTS FOR YOU PERSONALLY.”