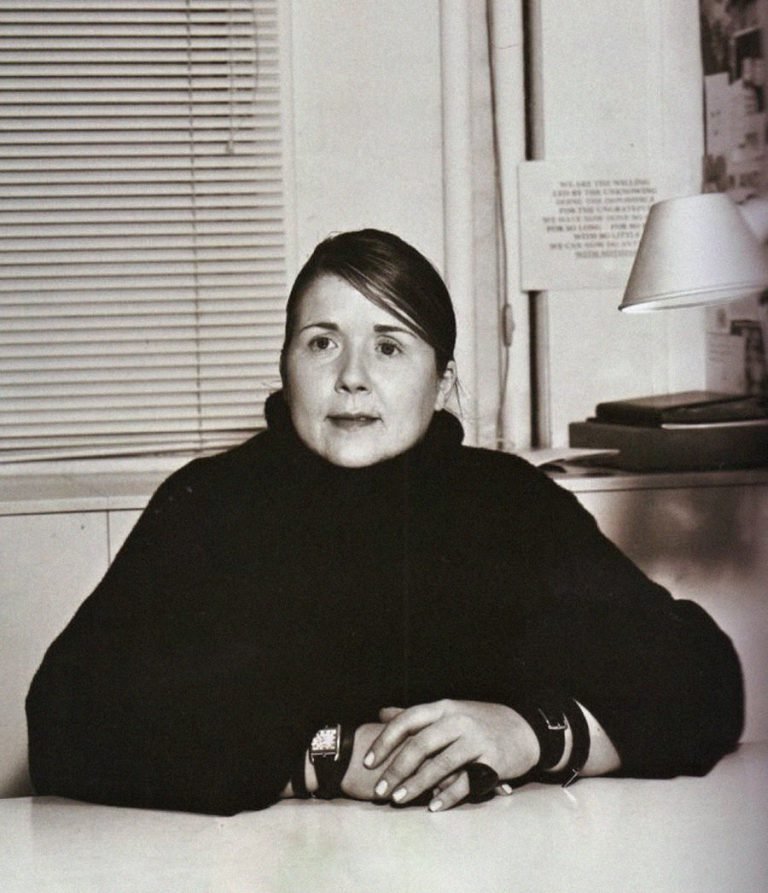

We had Kathrin Huesgen acting as a mentor through the entire process this year. What was the rationale there?

This year, we wanted to make it more rigorous. One of the important things from the journalist’s point of view is the ability to understand exactly how a designer works. So just to be thrown out there to shadow the designers and hope that they gain some technical knowledge was maybe a bit too simple. So we invited an experienced womenswear designer – Kathrin Huesgen, a German designer who has worked for many leading fashion labels in Germany, including Boss woman, which Jason Wu now designs. Because Kathrin was living in London at the time, she agreed that she would work closely on this project to help the journalists appreciate the technical aspect of what the designers were achieving and to ask the right questions of the designers in a way that perhaps I wouldn’t be able to do. I think that added a new element to it. What we have also done is encouraging students to collaborate, so for journalists to work with Fashion Communication students and to make it a final piece of work that is not only written in an interesting way, but is also visually appealing. I’m quite excited by what we have seen this year, although I think it is a bit of a trial year. I think next year and the year after, we’ll see something even better.

I remember you telling us that Louise would not even look at the visually unappealing projects, so was it her suggestion that we should collaborate with FCP?

Well, the funny thing was that Louise actually wasn’t very interested in the end results unless they looked beautiful. Since she never thought they looked beautiful, I never showed them to her in the end. I kind of gave up. But she agreed with the principle and what we were trying to achieve. She understood that fashion journalists were primarily focused on being writers and editors, not directors. She understood, and Fabio understands as well; he has been very supportive. They understand that what we’re trying to achieve is something that really helps the journalists to understand how designers’ minds work. It is good for them to be forced to talk about their work sometimes. It is a good process to go through. I know some of the designers definitely appreciate that. Some of them are very wary at the beginning and they have to be talked around and encouraged. In some cases, journalists have ended up being life long friends with the designers that they have shadowed, or maybe they are writing press releases for them, and helping them in all kinds of different ways.

Sometimes, of course, I think back to the Greek fashion journalist who shadowed someone like Christopher Kane. What a thrilling opportunity that was for her. Of course, he was just another student here but she had picked the right one. So that was a brilliant piece of talent spotting by her because the journalists make the approach to the designer. They are not assigned a designer to shadow.

There must be a lot of those in the archives from the alumni.

We don’t keep all coursework. That would be impractical. However, I have certainly been careful to keep really good coursework that comes across my desk. I make sure I keep it and eventually pass it on to the library. So, having said that, I really wonder whether I have got the Christopher Kane one somewhere. It is possible I gave it back to the student. So it may not be there unfortunately.

Do you recall any interesting things that have happened over the course of the shadowing project?

I think there are 2 things. One is obviously the details that you learn about the collections, and I love it. It’s my favourite time of the year when the shadowing projects come in. I love reading them because it’s fascinating. But apart from talking about the collection that the designer has created, there is also the human element that the journalists are invited to explore as well. We want them to kind of be a fly on the wall at every stage in the process and the big human drama every year is which students get into the show, and which don’t. I’m obviously talking about Louise Wilson, course director of the MA course for so long: her ‘showdowns’, confrontations, love ins with the designers over the years have produced extraordinarily powerful, dynamic, exciting, alarming, disturbing, thrilling copy. Brilliant. Most of which can never be published unfortunately. It’s highly confidential. That was always the understanding of the shadowing project. If you were going to have complete freedom to wander around the MA studios and listen to Louise having an argument with a student and then write it all down, it could never be published anywhere. So there are some pretty tough moments in there, and it is interesting from a human perspective to see how the designers have responded to the challenges put to them by their course director. It hasn’t always ended happily. It’s not like right at the end Louise and the designer reach an understanding and have bonded in a powerful way. That often does happen and that was magnificent when it did. I’m sure the same thing happens with Fabio as well. But there are also times when it doesn’t end happily and it’s quite upsetting actually to read the shadowing project if it really goes into the details of what went wrong, either in the collection or in the relationship between the designer and the course director, whether they are philosophical if they didn’t get in the show or whether they are bitter and hurt. So the shadowing project is fascinating on a number of levels which I think is brilliant. Just a shame they can’t be published.

Are they in the library though?

That’s another reason why I have been very careful about not putting them in the library. But I do believe that once time has passed, there is no need for these things to stay completely confidential. Maybe they could be put in there someday.