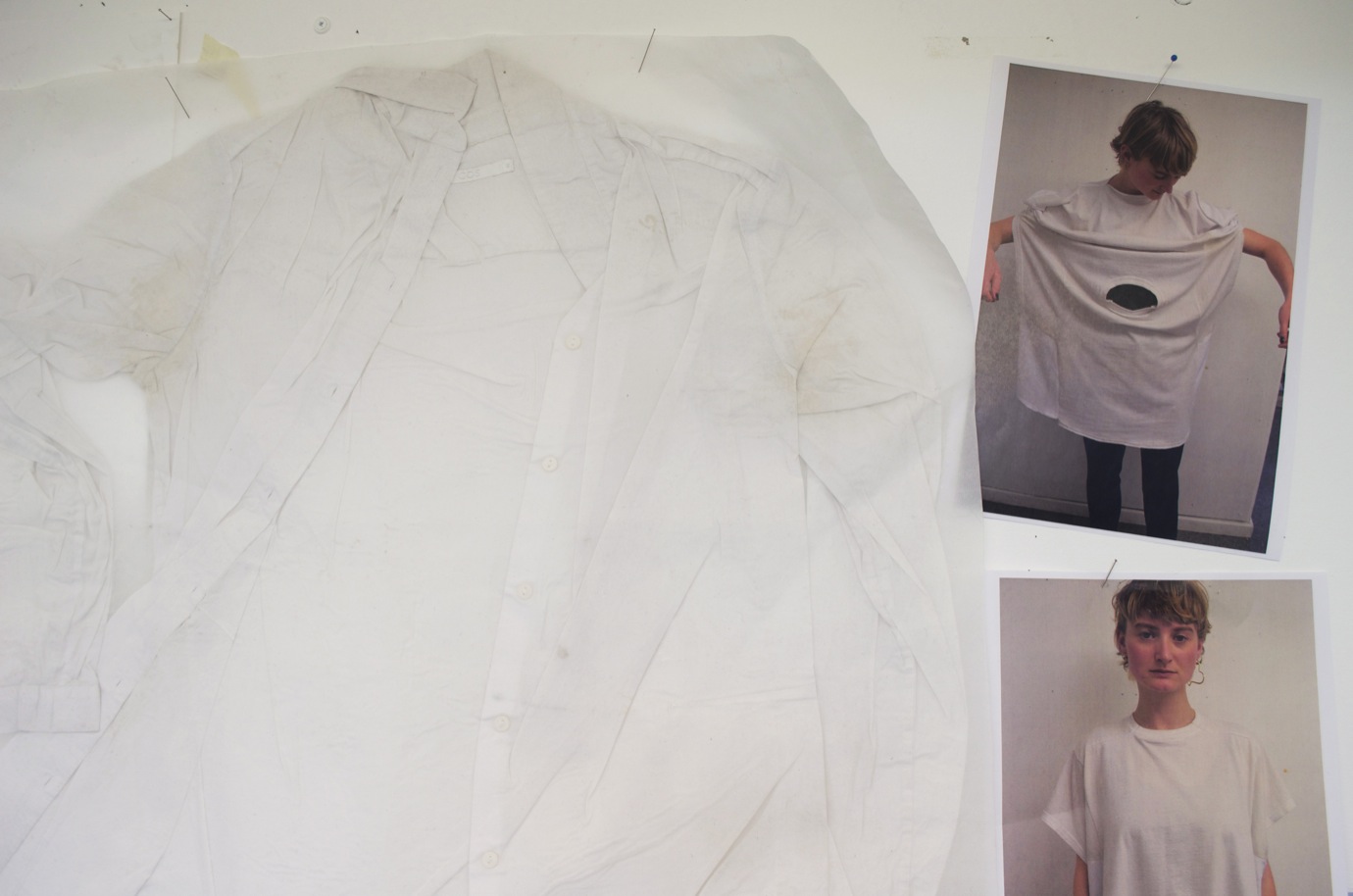

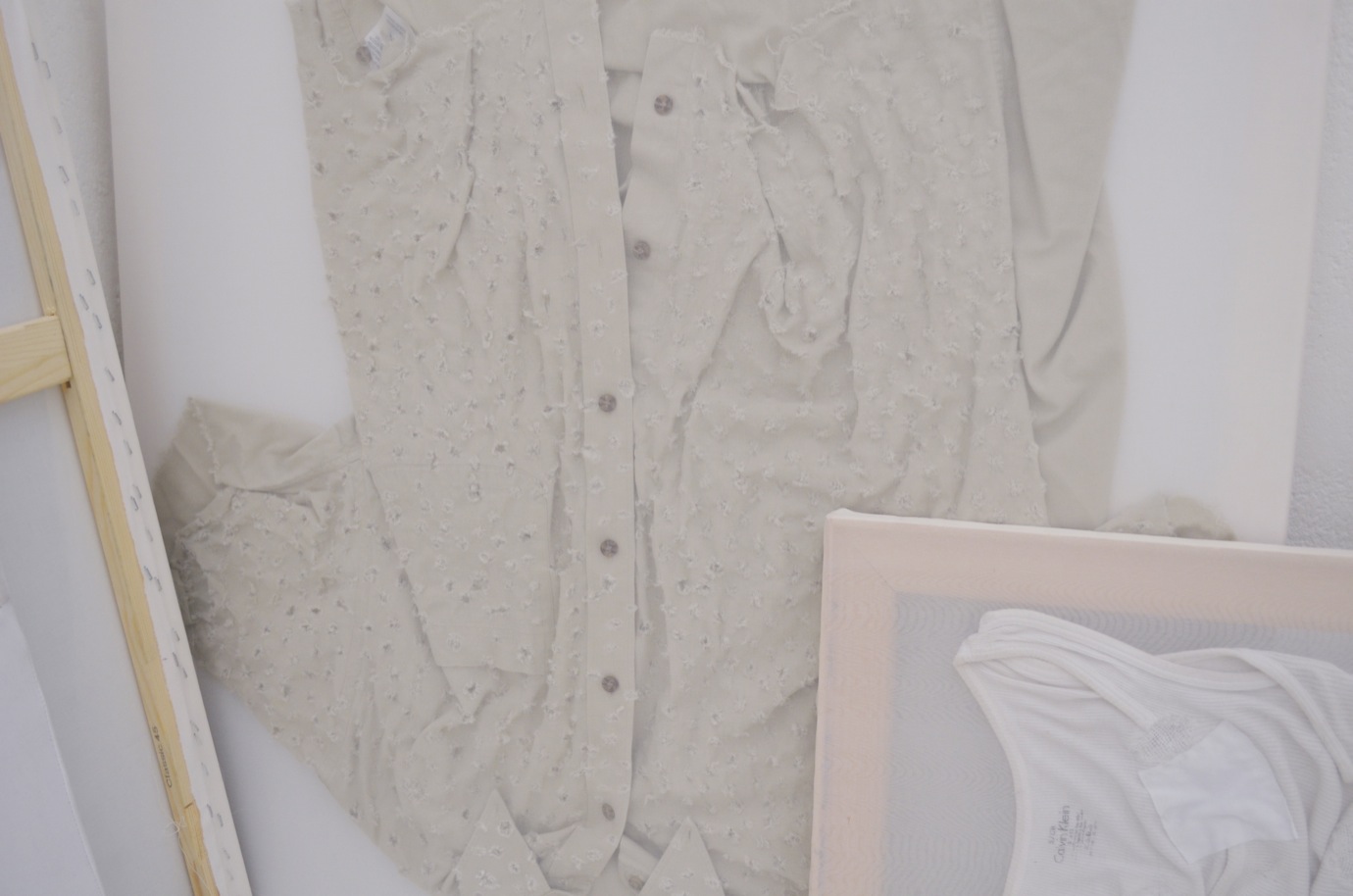

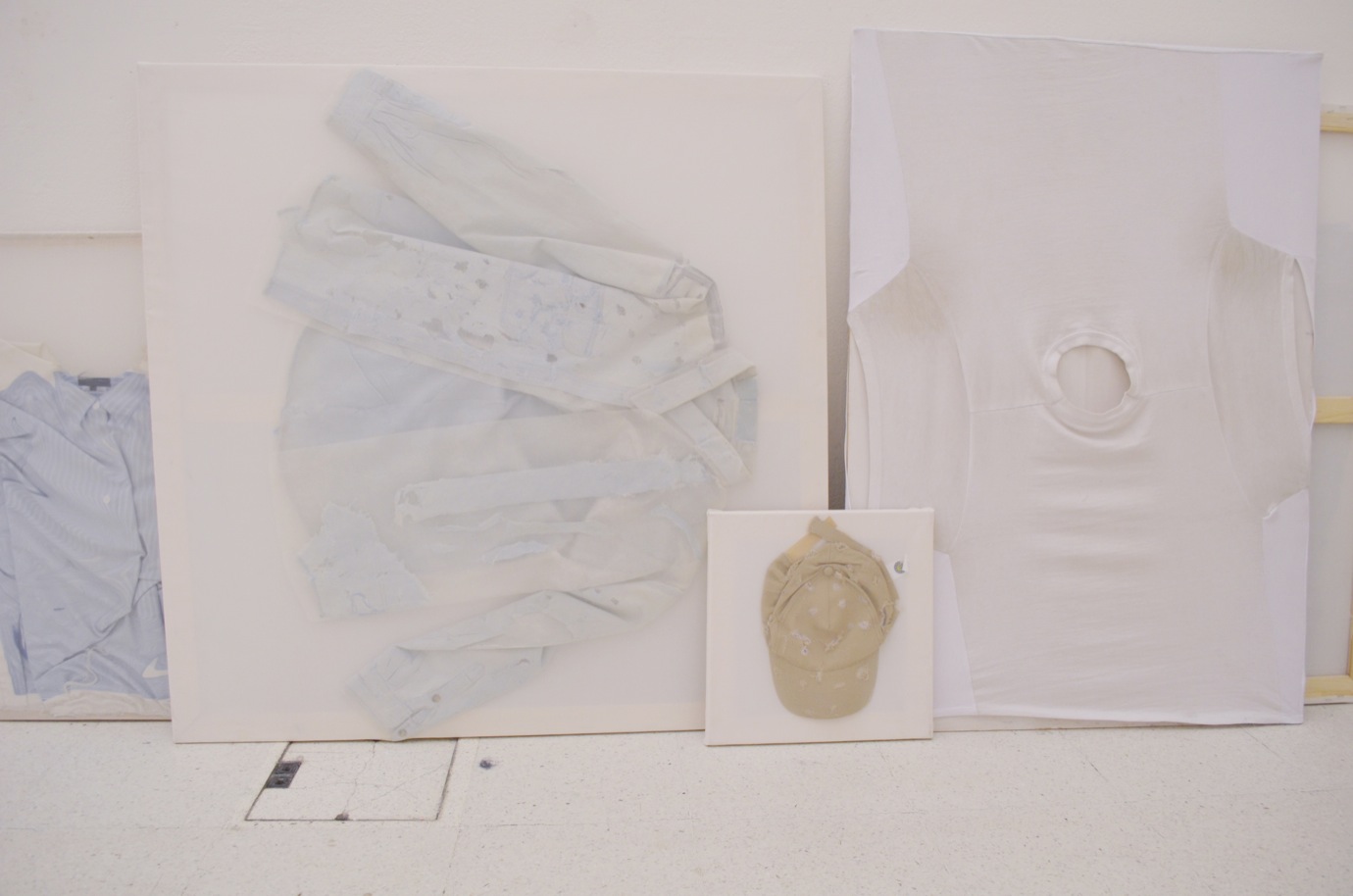

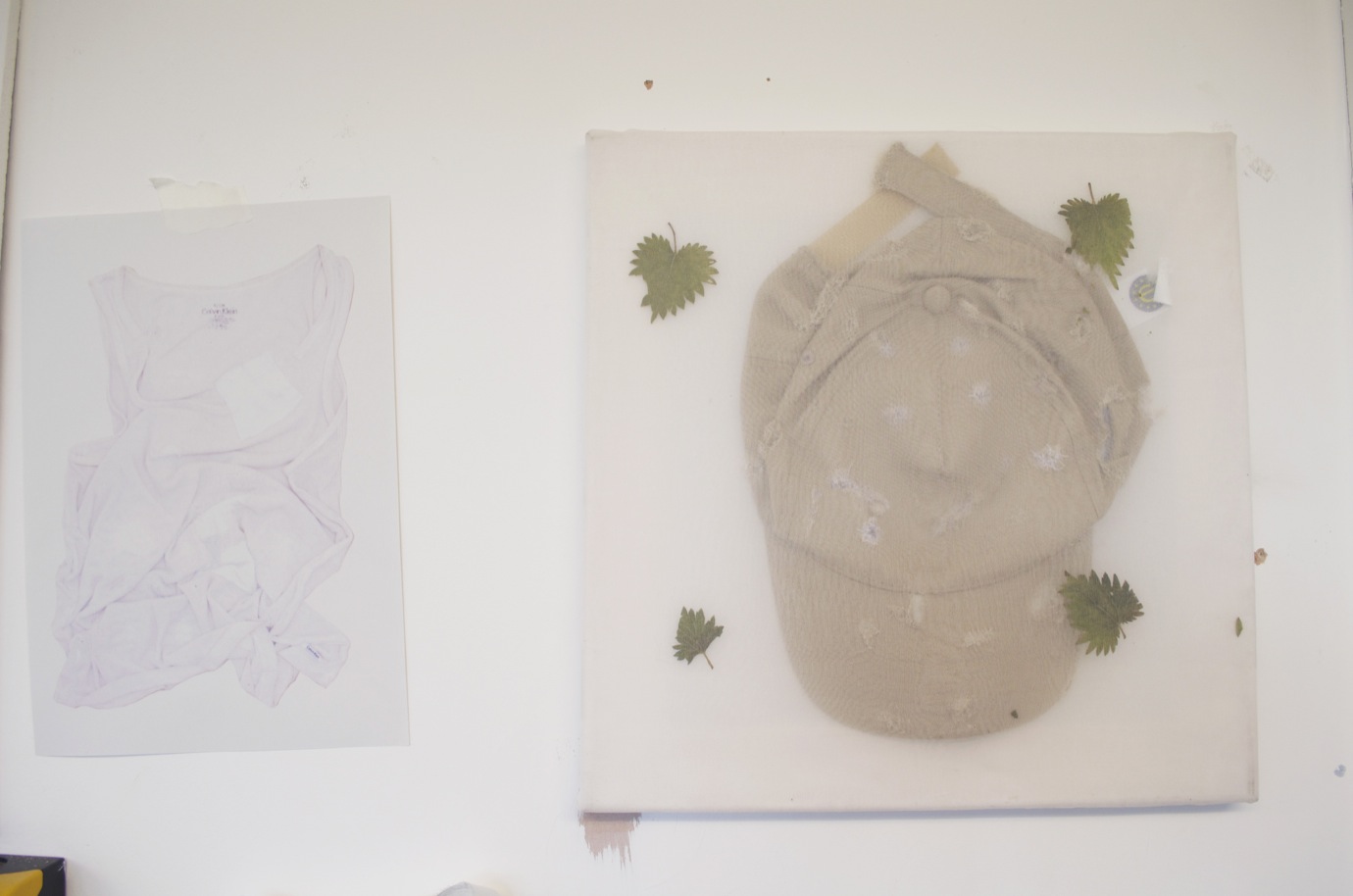

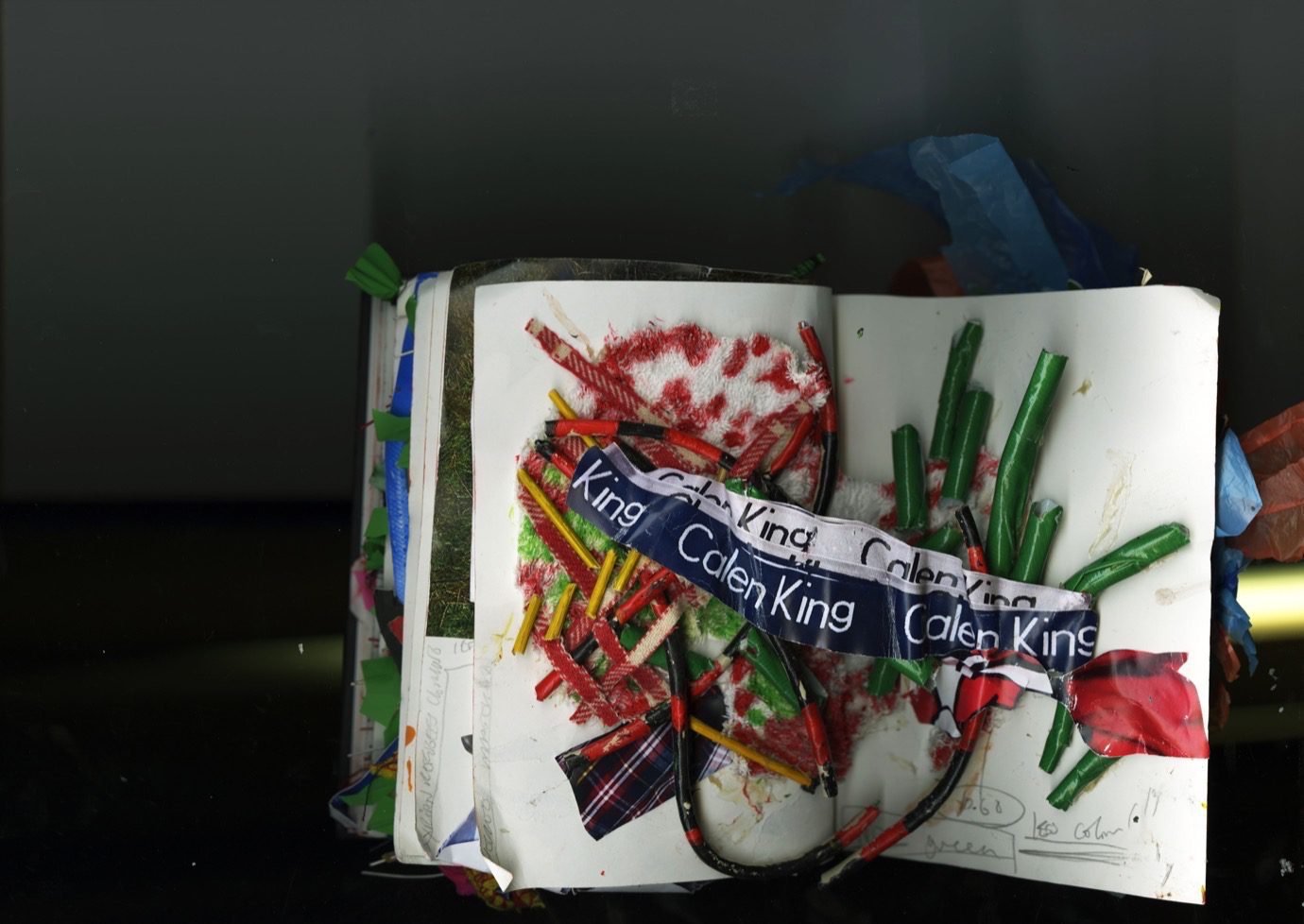

“WHEN I JUXTAPOSE THESE TWO ELEMENTS, THE FROZEN MOMENTUM AGAINST THE ROTTING FIBRE, I FIND MYSELF ASKING: “HOW DO WE DETERMINE WHAT IS IMPORTANT ENOUGH TO CONSERVE AND HOW DO WE DETERMINE WHAT CAN ROT? ISN’T IT BETTER TO LET EVERYTHING ROT AWAY AND MAINTAIN NO INSTITUTIONAL ARCHIVES ALL TOGETHER?””

Where did you study before and how did you end up at the Royal College of Art?

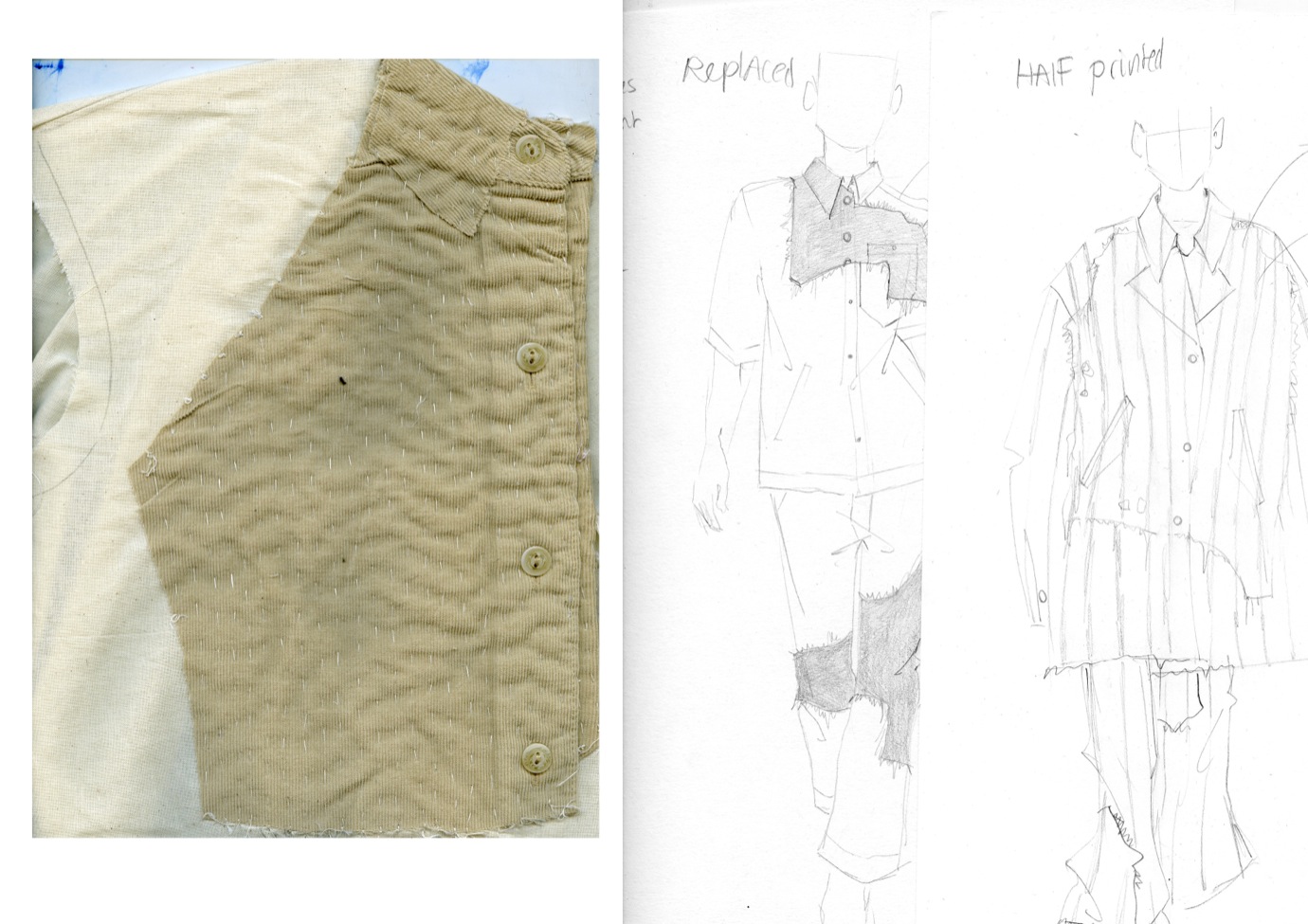

I did my BA in the Netherlands, at ArtEZ Hogeschool voor de Kunsten, where I studied Womenswear Design. After working in the industry for a bit, I realised I wanted to take my practise elsewhere, not completely away from fashion and garments but somewhere in between art and design. I went to The Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam where I studied Dirty Arts, which was a department that wanted to erase the division between the autonomous and the applied, and stimulated its students to pursue interdisciplinary practises. I did that for a year and then realised I wanted to develop my skills as a maker more than that education could give me, and made the final switch to Mixed Media at the RCA.

What was your experience like moving to London, and how does it compare to “home”?

I lived in London before, four years ago when I did an internship at Alexander McQueen, so it wasn’t completely new. Compared to here, Amsterdam is very tame, especially creatively, and there is not much space for alternative projects. It also doesn’t have a vivid diverse subcultural climate like here. Although I have to say that when it comes to fashion, I have seen an increase in the emergence of interesting and independent labels back home in the last two years.

What are some of the things that you like to do outside of college?

I don’t really have any hobbies. I guess that everything that used be my hobby has now all moved into being a part of my practice, like reading and drawing. I don’t make much distinction between leisure and work, the domestic and the professional.