July 2014:

I meet Denny for the first time at a bar in Frankfurt, where he is about to open ‘New Management’, an exhibition exploring the global rise of Samsung. Somewhat accidentally, I had just spent a weekend at a start-up conference in Berlin, and while my friends are only mildly impressed, Denny starts to fire questions at me: ‘What did you pitch?’, ‘Was it a lean start-up?’, ‘Were you going to bootstrap or to attract VCs?’. Clearly, the Berlin-based artist is speaking a language that I don’t understand. He is the figurehead of the tech-savvy artist-entrepreneur – a new type of artist, who has replaced the allure of the bohemia for the virtues of the white collar.

November 2015:

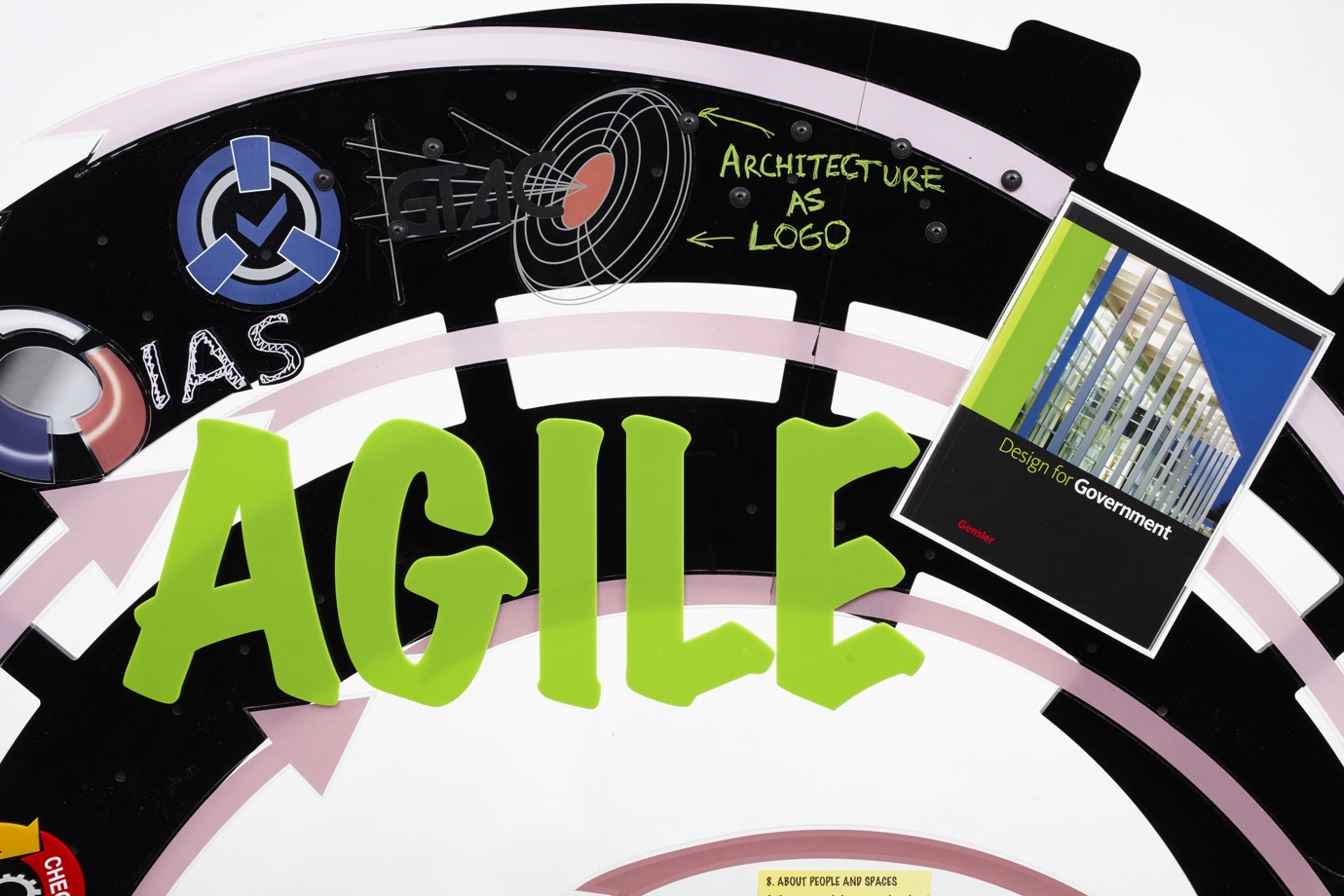

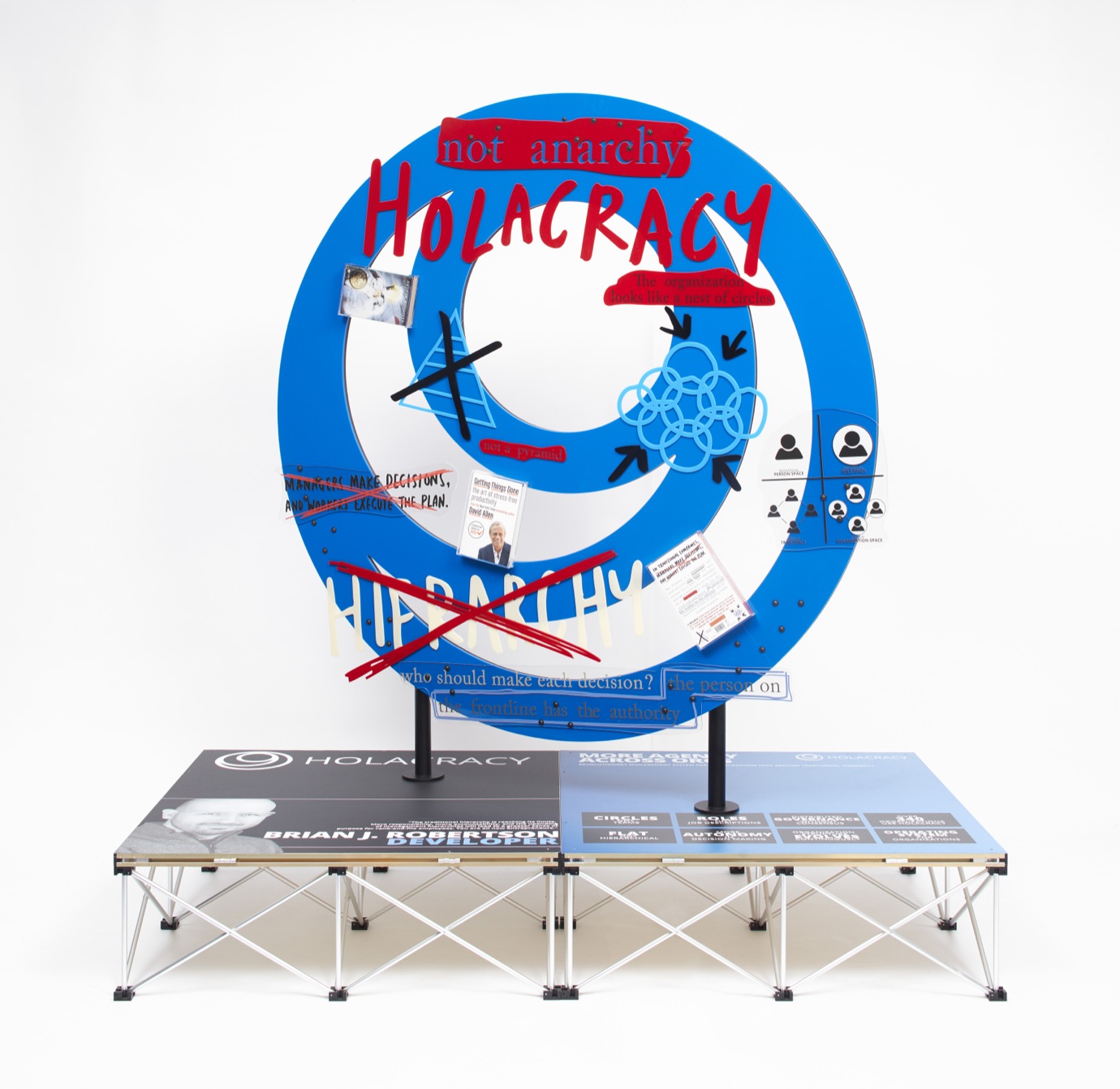

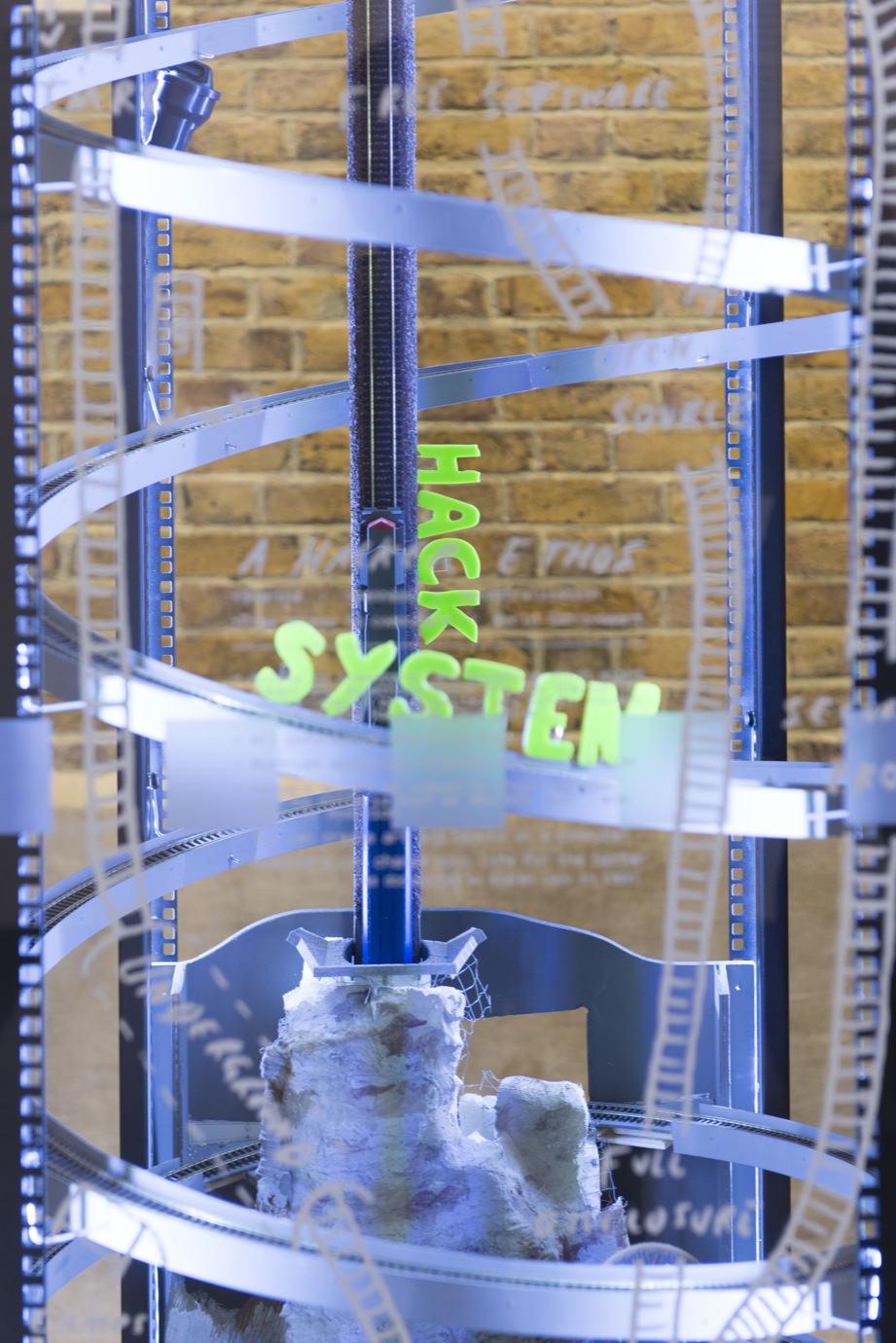

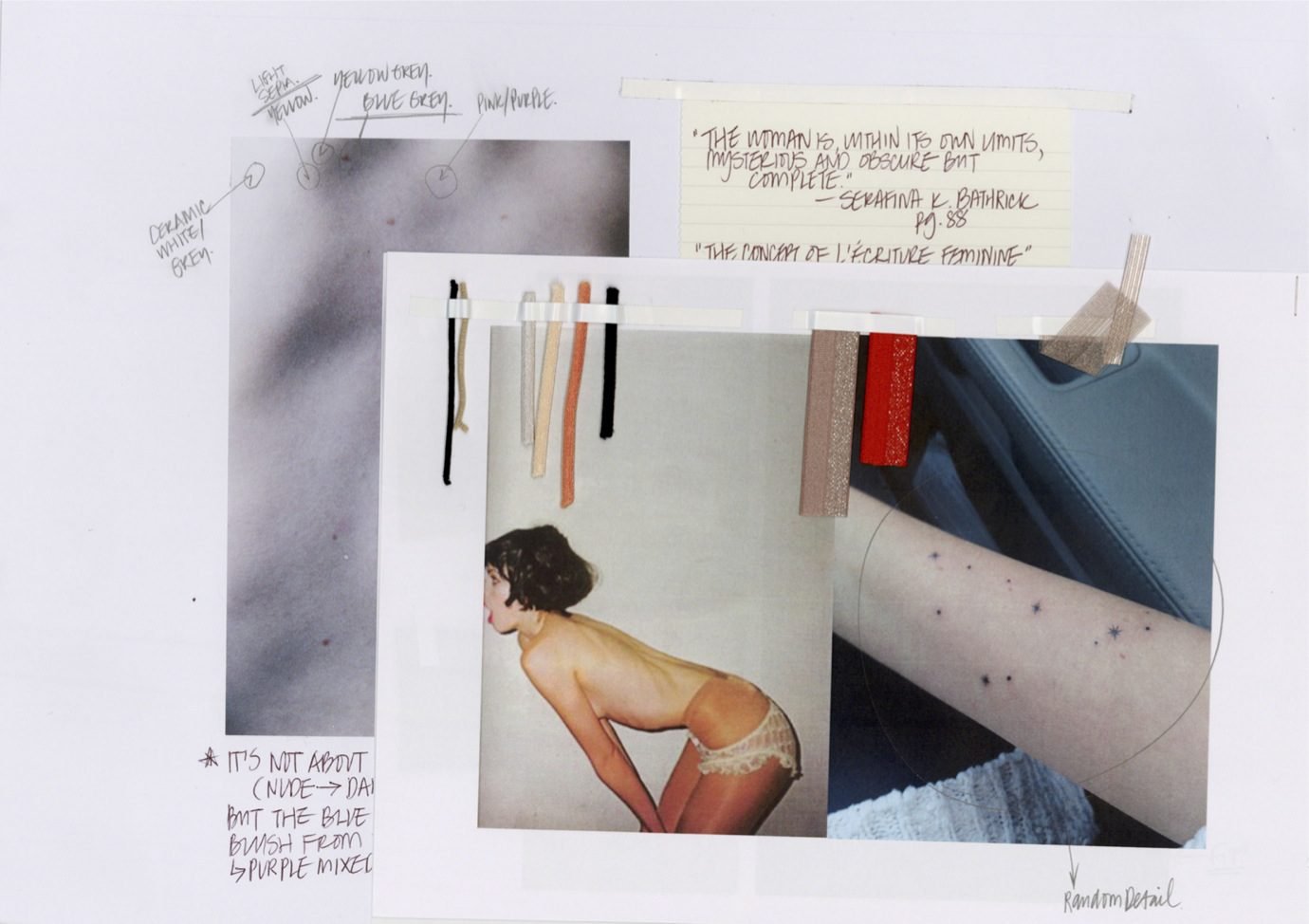

One week to go until the opening of ‘Products for Organising’, Denny’s first solo show in the UK. When I enter the Zaha Hadid Serpentine Galleries Café on a Tuesday morning, Simon Denny and Matt Goerzen, a Montreal-based artist and researcher with whom he collaborated for this show, are having coffee and discussing press releases. When I ask how instalment week is going, I am not surprised to hear that everything is set and done. Denny is on schedule, as always. Over the run of only three years, the 33-year old organized a TEDx conference in tax-haven Liechtenstein with fellow artist Daniel Keller, exhibited his own interpretation of Megaupload founder Kim Dotcom’s bizarre art collection, staged a show titled after start-up scene must-read The Innovator’s Dilemma at MoMA PS1 in New York, and commissioned freelance work from a former NSA designer for Secret Power at this year’s New Zealand pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale. Simon Denny’s practice evolves around the language and imagery of what has optimistically been termed “creative capitalism” – a stage in service-based economy where subjectivity, creativity, affectivity and empathy (once attributes of the idiosyncratic artist) have become sought-after currencies for disruptive innovation. In his densely packed exhibition designs, Denny tackles the contemporary mythologies of corporate power. Yet, he refuses to adhere to an either-or choice between critique and complicity. For him, contemporary art is most productive when it offers negotiable propositions, rather than fixed positions – and it is left to the viewer to make sense of it all.