Skelton’s inspiration has previously come in the form of social conflicts, often between two groups that divide his sympathies. Skelton’s graduate collection from Central Saint Martins covered the Mass Observation, and his last collection took on the legacy of British interventions in India. It was while working on this collection that he organically found inspiration for his latest, which he calls The Radical North. Listening to Melvyn Bragg’s The Matter of the North on BBC Radio 4 while he worked with his hands on his own pieces, he became entranced by the notion of a politically radical North created by the garment-makers of the past, a political movement built of men who worked with weaving, looming, and knitting.

His focus landed, most particularly, on the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, when a group of cloth workers gathered peacefully to demand the vote, and were charged by a local yeomanry force commanded by the upper classes. The audacity of craftsmen asking for their voices to be heard was met with extreme violence from men they had considered neighbours and friends. The brutality of the event spurred yet more voices to call for equality, and the Chartist and Suffragette movements owe their creation at least in part to this event.

Almost 200 years later, as he experienced the cognitive dissonance of Brexit campaigners and the subsequent outcome from his base in London, Skelton too was “furious” at first about the northern vote to Leave, crucially, from members of his own family. Slowly though, he became tired of the damning attitudes of many Londoners towards the descendants of those they owed their vote to: “People’s attitudes were incredibly damning of people who did vote out, and I didn’t think that was fair. It was almost like people shouldn’t have been allowed to vote…”

There were unmistakable parallels with the North versus South conflict of 19th century society, and Skelton once again found himself caught between two worlds. “People really don’t know their history,” he explained, “or what someone has done before them, what someone has endured before them, and what incredible freedom they have now. I wanted to bring that to light.” Though he would still vote to remain in the EU, John gained a certain respect and even admiration for the people of the North who had made such a radical decision and effectively removed political power from London, if only temporarily.

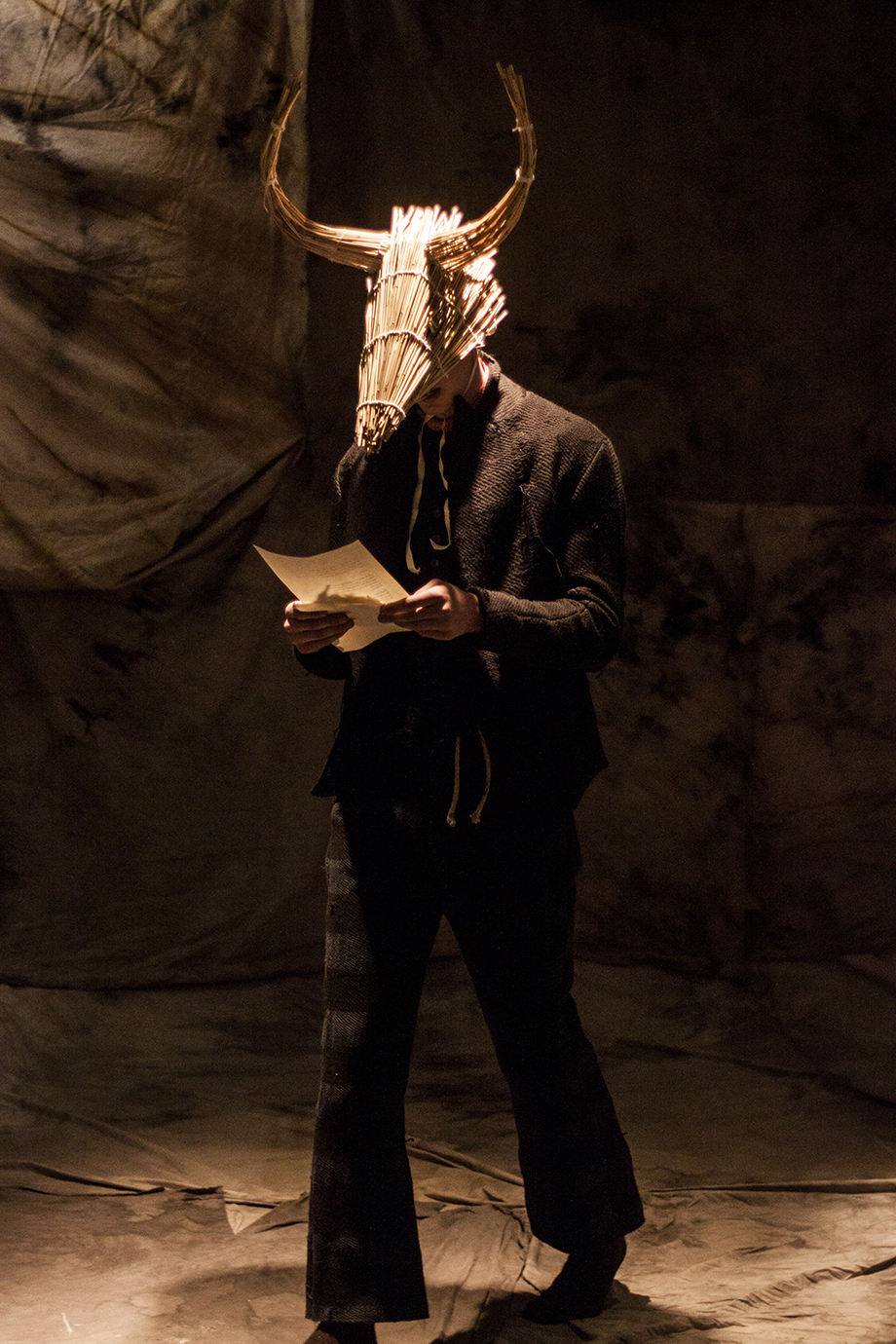

From this starting point, Skelton read of secret Chartist meetings, and the sartorial signs that became integral to a sense of community for people who frequently were illiterate. Though the movements spawned by Peterloo carried banners and written material, they relied hugely on colour or small features of their clothing to indicate their political identity. Multicoloured sashes, previously associated with folkloric dress of Morris dancers, were popular, as were more subtle ribbons in buttonholes. “I was interested in how something so subtle could be so powerful en masse.” Further down the rabbit hole of British folkloric traditions, he adopted the homemade embroidery of pagan style symbols associated with Mummers and Pace Eggers, traditions that almost died with the young men slaughtered in the Great War, but kept alive today particularly in Lancashire and Yorkshire.

“PEOPLE REALLY DON’T KNOW THEIR HISTORY. OR WHAT SOMEONE HAS DONE BEFORE THEM, WHAT SOMEONE HAS ENDURED BEFORE THEM, AND WHAT INCREDIBLE FREEDOM THEY HAVE NOW. I WANTED TO BRING THAT TO LIGHT.”

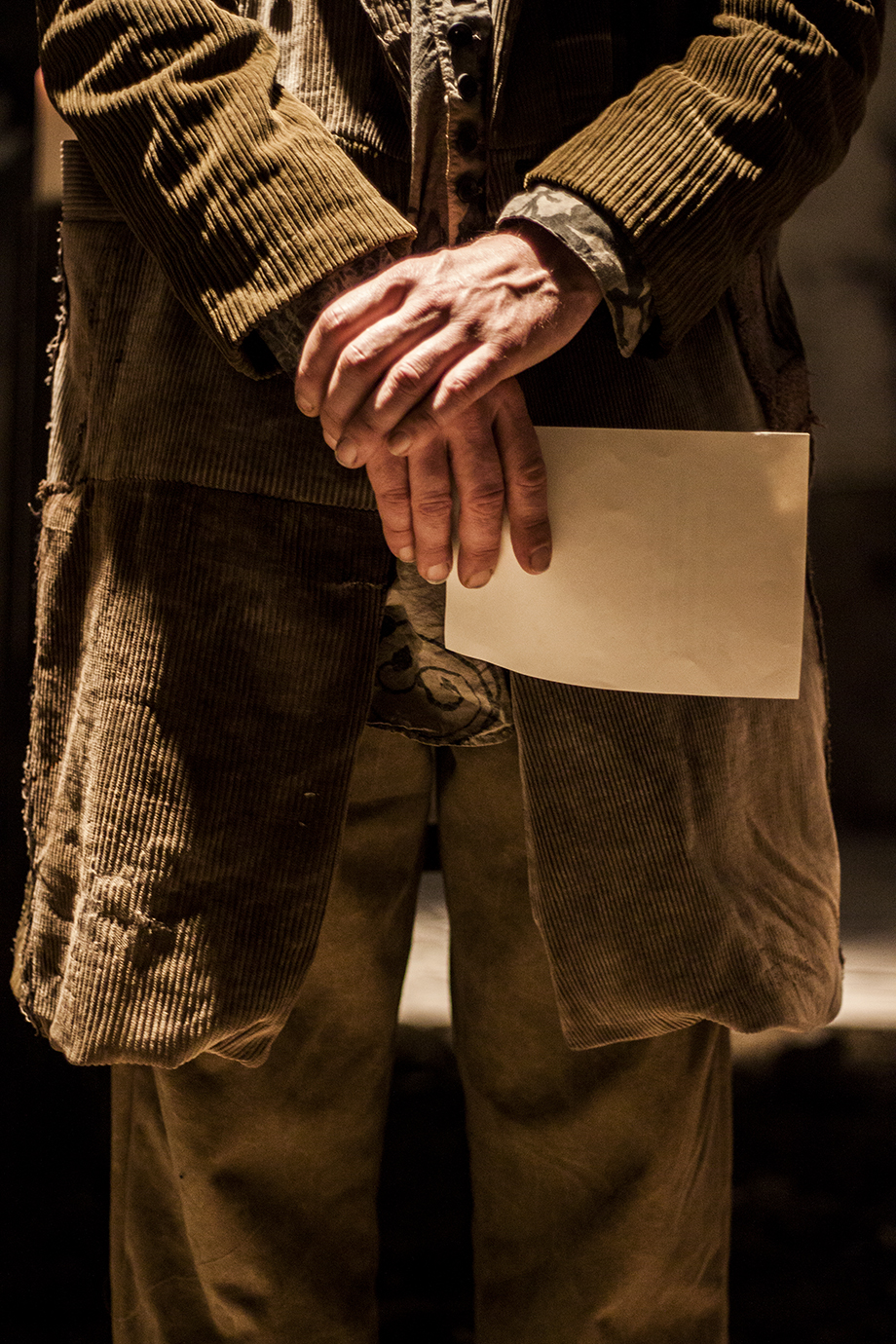

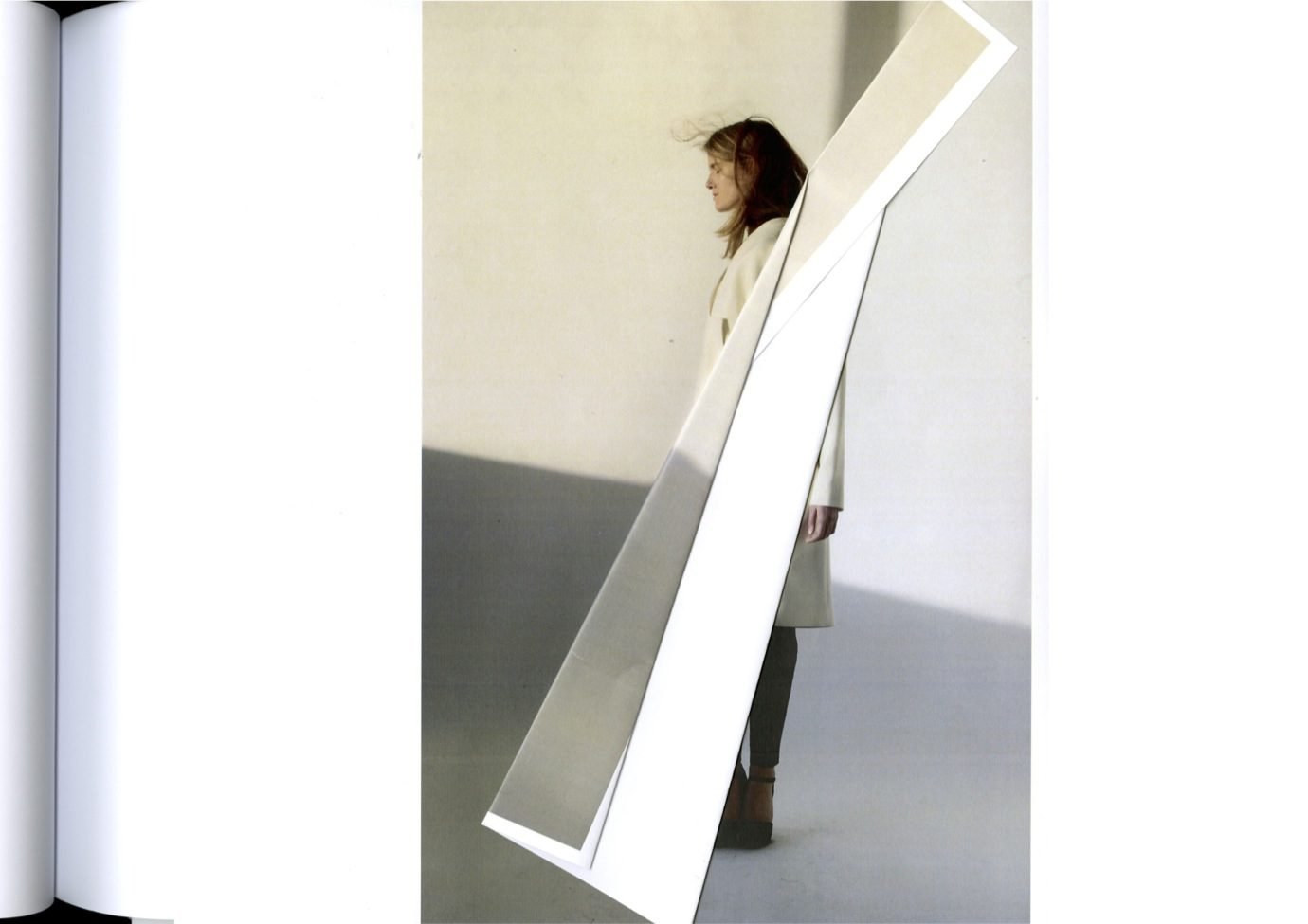

Despite such visually rich inspiration, rooted in a specific time period, the clothing manages to avoid looking like a costume.The content is not merely the facsimile of a working man’s wardrobe from the early 19th century. Rather, there are modern pieces, crafted from a tartan created for one of the Chartist orators, fabrics made on old hand and tapestry looms, and handmade knitwear from Shetland wool. An unmistakable pride in hard work comes across as Skelton expands on the time-consuming process of producing tapestry and creating patchwork, as well as a genuine affection for his favourite pieces – he decided not to put shoes on the models to properly display the “quiet beauty” of hand-knitted socks, as well as admitting himself to be “enamoured” by a pair of gloves he commissioned from a specialist glover to commemorate the date of Peterloo.

As we have seen from previous collections, Skelton’s garments are products of a process of exploration, experimentation, and learning – both about historical events and technical skills. “I really like to learn something when I’m doing a collection. It’s an inherent part of my process, that I need mentally. I don’t want to be making clothes just for the sake of making them.” The end result has been the synthesis of his own socio-political responses, an aesthetic reconciliation of an involved social conflict.

The first and second collections allowed us to remain passive, Skelton’s harmony and resolution appeared as his personal domain. There was always a cultural, geographical, or historical distance to facilitate a personal cleavage from the heart of the matter. This collection is not such easy viewing material; it is not a resolution. It is a question that demands an answer. This is particularly evident in the way the collection was presented.

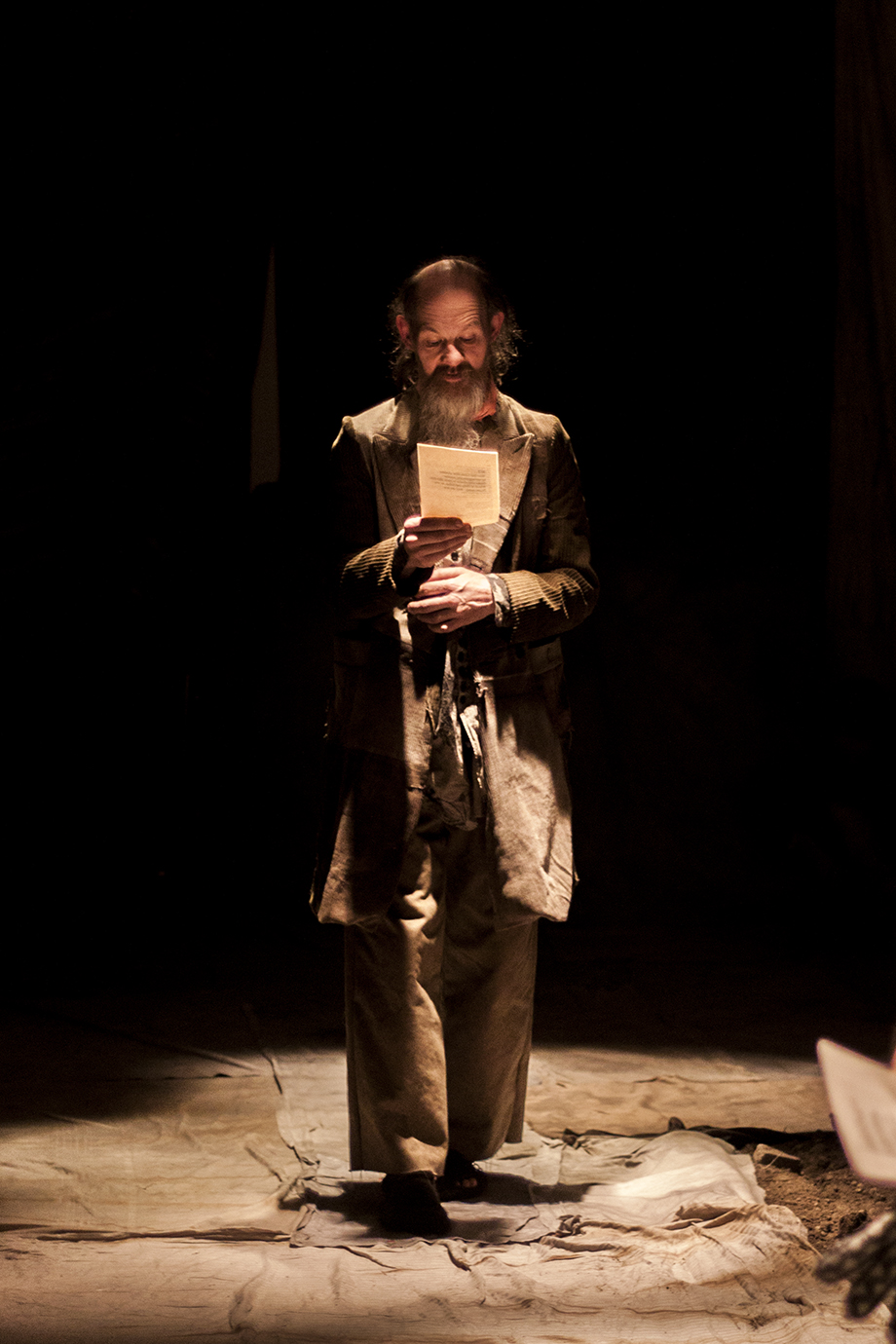

The showing, at the Sarabande Foundation, was modelled on the secret Chartist meetings. Skelton aimed for “an immersive experience” with a theatrical feel, but it felt like a call to activity, or at least a call to reflection. It drew the attention of London’s creative community, a stronghold of support for the Remain campaign, to the origin of their democratic freedoms: the very people they castigated following the EU referendum, and whose rights to vote they half-facetiously suggested should be revoked.

There is an undoubted progression in Skelton’s work here; no longer happy with presenting his own reconciliations, he challenges the public to consider their own. Even the models are not passive, they were chosen in part for their northern accents, to bring an authenticity to a live recitation of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s The Mask of Anarchy, inspired by the Peterloo massacre. Its final stanza too demanded engagement, and a response from contemporary readers.

‘Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number –

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you –

Ye are many – they are few.’