On paper, Powell’s film industry accomplishments make her a Central Saint Martins anomaly, but listening to her recall her time there you realise it was not too dissimilar to yours or mine. “I was really was very bad at college,” she says of her foundation course and a year-plus on the theatre design BA. “I didn’t do much work – I socialised.” Even though ‘Central’, as it was known then, was the most fashionable school to go to, it was a time before the fashion department prevailed. “More people ended up in punk bands,” she says. Naturally, she outfitted them. Her inner circle included the choreographer Lea Anderson, whom she spent idle pub lunches with, and many of the DIY performers and sculptors that defined the generation (it was the late 1970s).

*This feature originally appears in 1 Granary Issue 3: Dazzling in an age of austerity

Sandy Powell avoids clichés. “I grew up in Brixton and Clapham but I’m not going to say that being brought up around West Indian families made me have an interest in colour,” she says in response to the vivid hues that punctuate much of her 30-year career as a costume designer. Yet still, the truism ‘be your own work’ comes into mind when you meet her. Powell’s airy Brixton home, a place she’s occupied for 20 of those years, is filled with saturated tones straight out of “Velvet Goldmine”, the darkly charged glam rock portrait that earned her one of her first Oscar nominations. Her current tally is ten, including three wins (“Shakespeare in Love”, “The Aviator”, “Young Victoria”). In her dining room hangs an electric blue portrait by LGBT artist Sadie Lee, while the deep orange walls in the upstairs sitting room aren’t too dissimilar to the current shade of her hair (it was purple-red when she collected her OBE in 2011).

“I’VE REALISED IF IT’S NOT SOMETHING I WANT TO SEE, WHY SPEND NINE MONTHS OF MY LIFE ON IT?”

With Arts Council funding in tact, London was a playground for experimental theatre companies that showcased the protean power of clothes. What “sewed the seed” for Powell was an encounter with Lindsay Kemp, the maverick choreographer who taught Bowie dance and mime, who took her under his wing after being impressed with her personal style. “I went up to him after a show during my work experience year – in a purple Louise Brooks bob and purple harem pants – and said I’m a student, I love your work, can I show you mine?” She never made it back to college.

“Another time I cold-called somebody, it was Derek Jarman. Having done theatre for a couple of years I thought, I want to do film and I want to do his films. And I got his phone number via a friend in Heaven [the club] and said, do you want to come see a show I did at the ICA?” The chance of reaching your icon this way today seems as likely as an increase in arts funding. “Oh God, of course you wouldn’t do that now,” she quips. “I would be horrified if somebody just phoned me up!” It’s her shyness towards show business, not an unwillingness to nurture young talent that elicits such a comment (budding costumiers rest assured, I witness a CV being opened that came through her letterbox that morning).

“I was extremely lucky that the people I admired took me up, someone completely inexperienced, and were generous with their knowledge,” she continues. “They were my first teachers, better than some of the teachers in college.”

Jarman, for instance, introduced her to the world of pop videos – or “mini films” as he called them – until bringing her in on her first feature production and a costume designer’s dream, “Caravaggio”. “I realised a Derek Jarman film is not normal film-making. He’s an artist and a designer and he treated each job like it was a party.”

Powell has cleaved to that artistic vitality throughout her career, but is lucky to have struck the indie/mainstream balance to be “above the bread line”. It’s a much-sought after but rarely occupied place. “What I spent most of my career doing isn’t the really low budget – student projects, is what I’ll call them – but mid-range dramas,” she says, having once referred to Martin Scorsese as an art house filmmaker with a bigger budget. They’ve now collaborated together on six ‘art house’ classics.

Those projects are a costume designer’s rare luxury: time, quality of craftsmanship and an opportunity to hold out for a fund-seeking labour of love. Take “Carol”, director Todd Haynes’ generational romance between two women in 1950s America, which has been 11 years in the making. Driven by a stellar lead cast, Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara, the film finally premiered at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, and earned Rooney the sought after Palme d’Or award for best actress in the process. “There are still very few female-driven films,” notes Powell, letting her own political leanings emerge. “And the money for mid-range projects has gone.” Luckily, she treads the same waters as a handful of industry veterans who take a critical lens on the structures of gender, sexuality and class.

“Nowadays there’s a lot of work around, but it’s all aimed at the lowest common denominator,” she says. “It’s all mega buck franchises parts 1, 2, 3 and 4, or it’s Marvel or Disney. This format works – let’s do it again with some other people in it. I would rather make considerably less money on something that’s good than do the whole superhero thing.” It’s why she’s had the last year off, and still hasn’t confirmed her next wave of films. “I’ve realised if it’s not something I want to see, why spend nine months of my life on it?”

“I’M NOT AN HISTORIAN, I DON’T RETAIN EVERYTHING. I’D DESCRIBE IT LIKE DOING EXAMS AT SCHOOL–YOU DO THE REVISION AND FORGET ABOUT IT A WEEK LATER.”

Besides her innate sense of style, the Vogue Italia lying on her dining table makes me wonder whether she’d consider a parallel career in fashion – to fill the gaps, so to speak. Her styling work for a Tim Walker Love shoot, for which she cobbled together a cellophane dress that Karen Elson wore, could be just the start. “I enjoyed it… Katie Grand was pulling Dolce & Gabbana and I was doing my thing but I think the combination of the story worked.” Unsurprisingly, directors often ask her to include a fashion element in their productions (she’s seen far too many McQueen imitations in others).

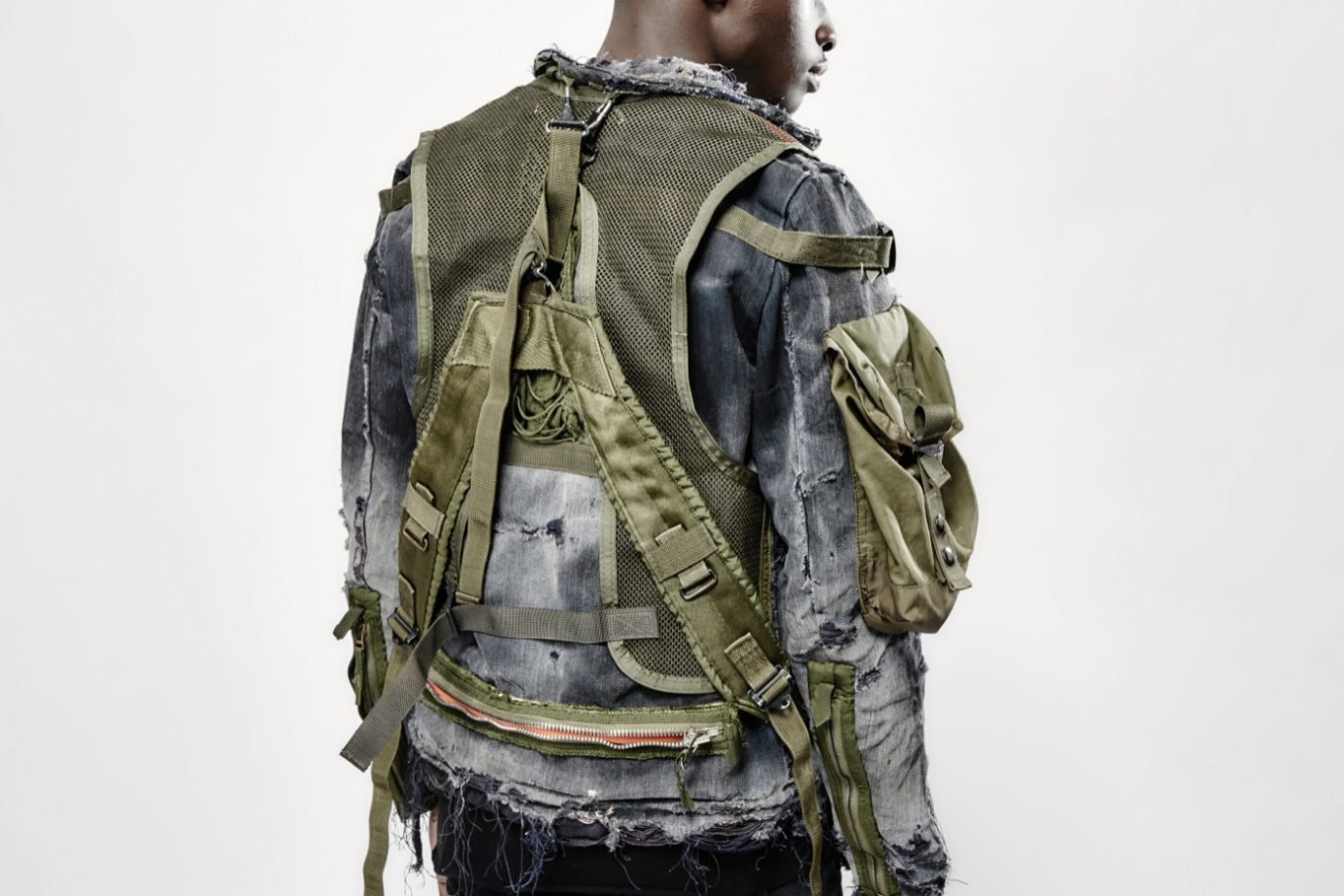

“I would consider it if it involved what I do as opposed to being given a load of a fashion designer’s clothes that I have to put on a model,” she says. “That, I’m not particularly interested in doing.” She’s an avid collector of clothes, too, from the Belgians and the Japanese she wears herself to vintage Jean Paul Gaultier. Fashion characterises her thinking: she enters the mind-set of a designer in the periods she recreates; some are steeped in reality, others in a meticulously invented world such as “Gangs of New York”. Harvey Weinstein, the film mogul who produced the crime epic, has said Powell’s talent lies in her ability to inject modernity into historical costumes so often portrayed in our culture. “I always take artistic license,” she admits, priding authenticity over accuracy. Her only criterion for a project is that it’s “not dead boring.”

For films set in the age of pre-photography, the larger part of her work, she begins by looking at art from the period and consults technical costume books. “Then where possible I look at the real costumes by going to the V&A or wherever you can have a look at the real thing.” Then she goes broader than that. “When I’ve actually looked at the specific period, I look at the characters, and I think of the feelings and colours for scenes. Then I go into other periods; other paintings that I like or fashion from that era, fashion from anywhere in the 20th century.” Most importantly, she notes, “I really believe you can pick out any book from the shelf and there will be something you can reference.”

“Whatever period you are doing, you can pick out a Tim Walker book or a book of Balenciaga or one by a war photographer and there will be at least one image that you can use. Even if it’s just a texture on a piece of fabric or a texture in a landscape that would look good on something or a colour combination.” You suddenly realise how her puzzle-like line of work takes on a heightened fantasy.

Powell throws herself into jobs with only one or two research assistants in the early stages, and often gets an idea for a costume in a fabric shop rather than from a piece of paper. “Every time I get stuck, I go to Shepherd’s Bush: the cheap shops, which are overflowing. Quite often there will be a colour or a cheap texture that nobody would have thought of bringing to me.” The visual cornucopia is then gathered into a reference book, some of which have ended up in college libraries. She doesn’t get sentimental for them, she says, and simply keeps digital copies of her drawings. Naturally, “little bits of everything” live on in her loft: “a Leo, a Tilda, a Daniel Day Lewis.” Julianne Moore, whose contract includes ownership of all her costumes, let her keep the pieces she made for “End of the Affair” and “Far From Heaven”. For the latter, each scene was allocated with a different Pantone colour.

The fruits she reaps from each project carries over into the other, much like an artist’s or a designer’s undisputable vision. She credits a recent stop by the travelling V&A exhibition Hollywood Costume for making her realise she dressed two Elizabeth I (Judi Dench in “Shakespeare in Love” and Quentin Crisp in “Orlando”) in an over-gown made of the same printed velvet fabric. “I’m not an historian, I don’t retain everything,” she admits. “I’d describe it like doing exams at school–you do the revision and forget about it a week later.” It’s an out-of-this-world exam she is sitting; period may be her chosen subject, but contemporariness is an over-gown she wears well.