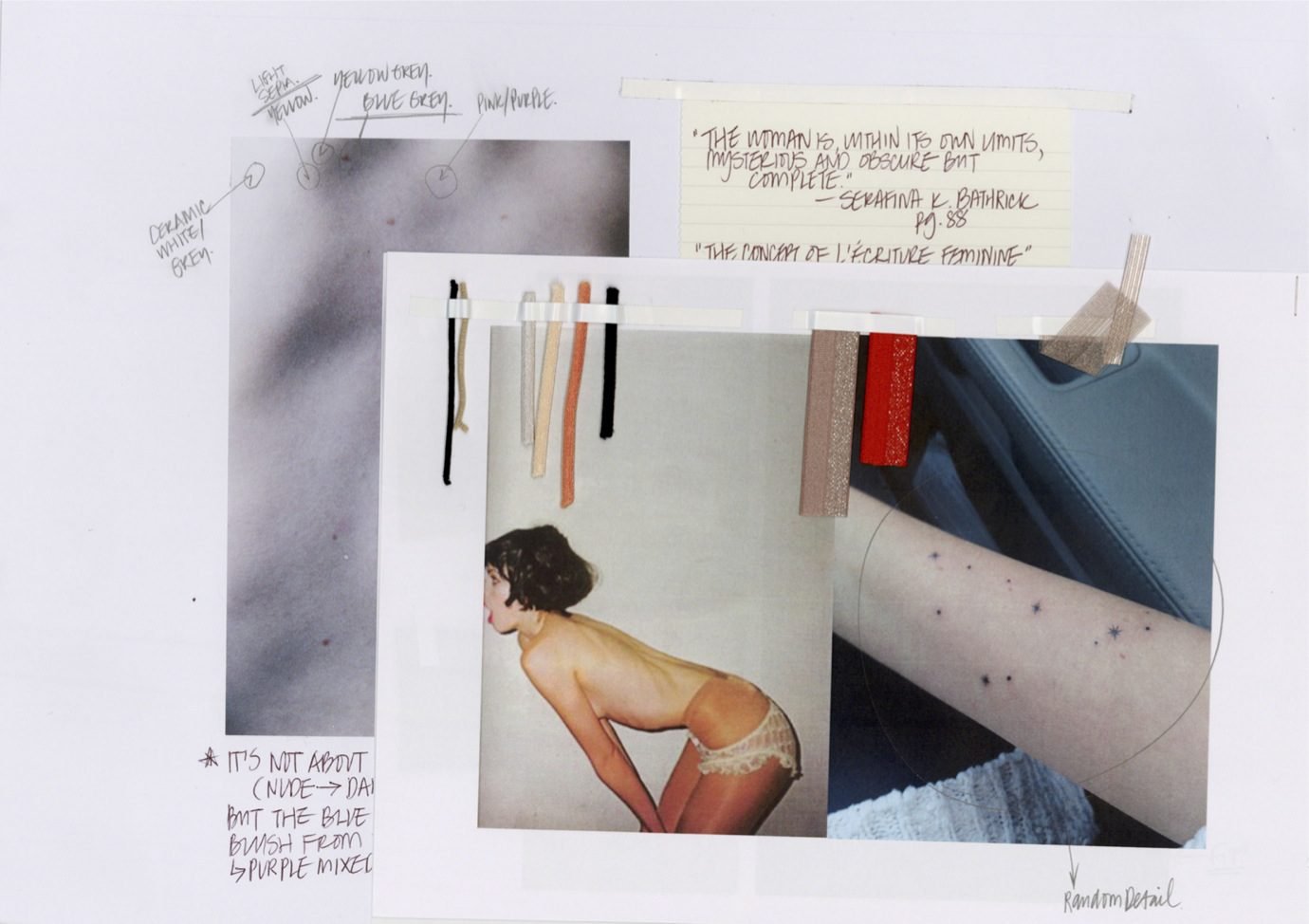

But what a world that is! It is rare to find a collection that is as intimate, emotional and conceptual as this one. Still waters run deep, and so her minimal silhouettes – long A-line skirts and turtlenecks in a muted palette – are only the surface of her complex story.

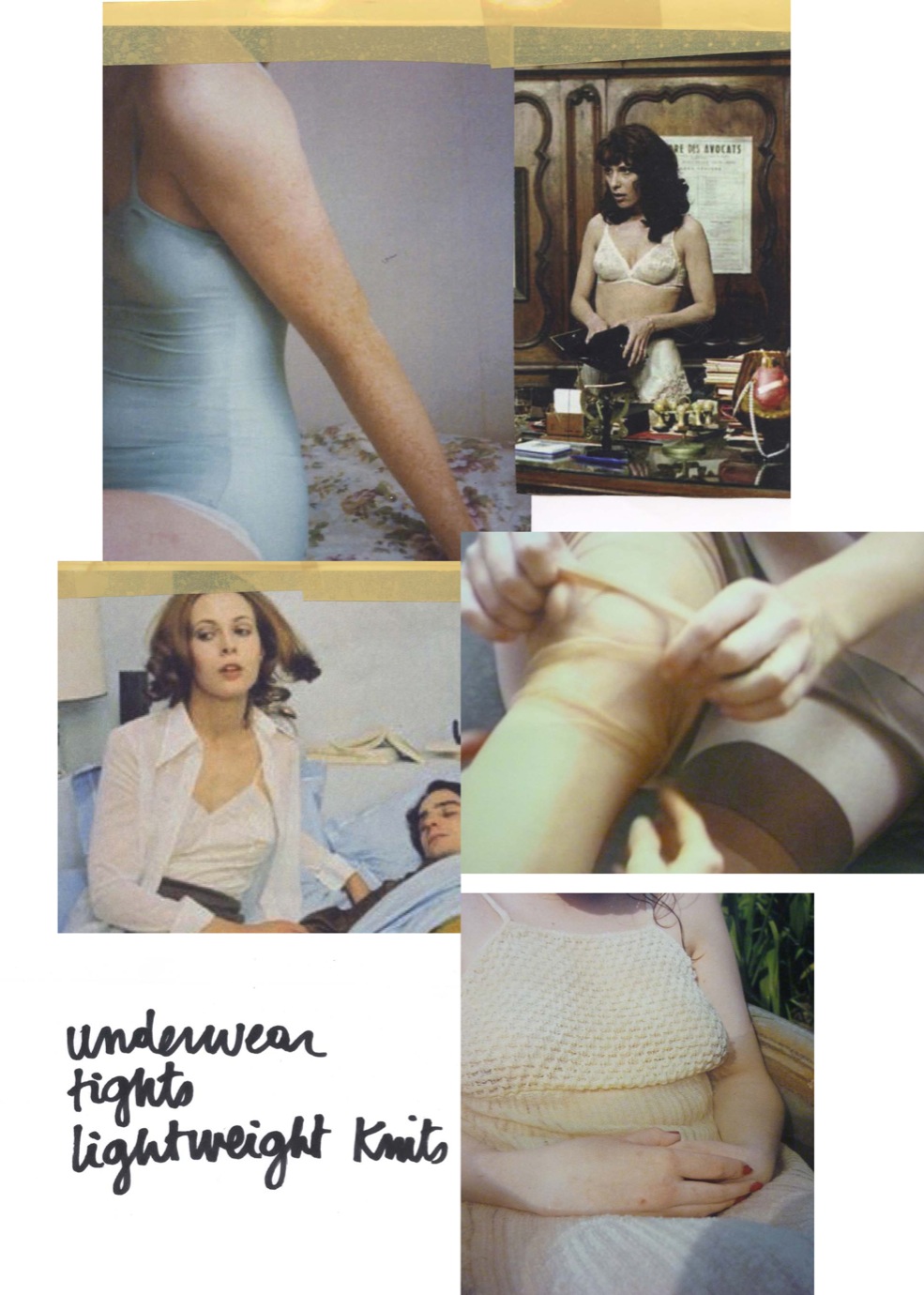

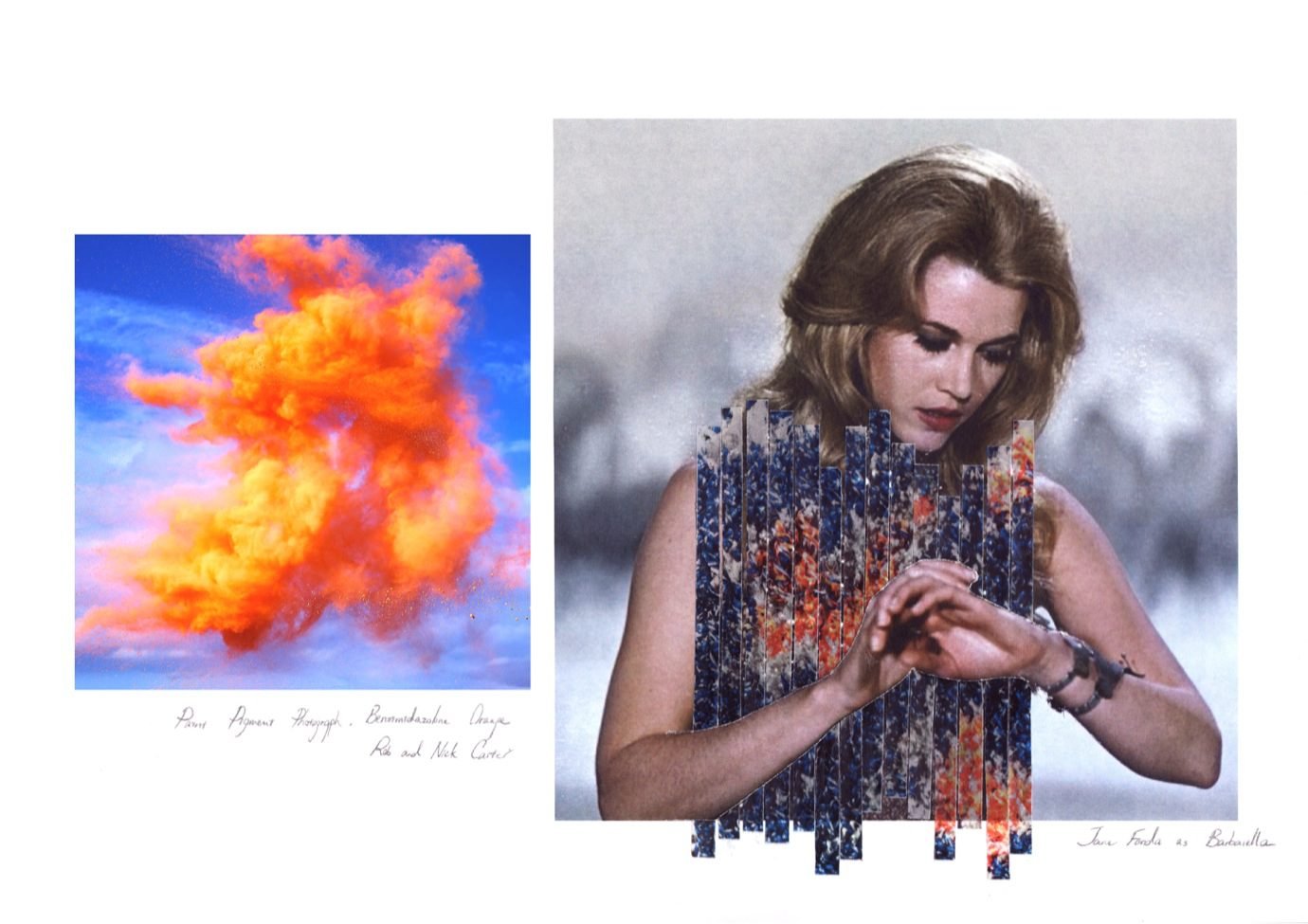

It started with a movie: Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce by the Belgian experimental filmmaker Chantal Akerman. Through three hours of tableaux vivants Akerman shows the daily life and desperation of a middle-aged housewife. “When I first saw the movie I was stunned,” Amélie says “everything is so recognisable yet so strange.”

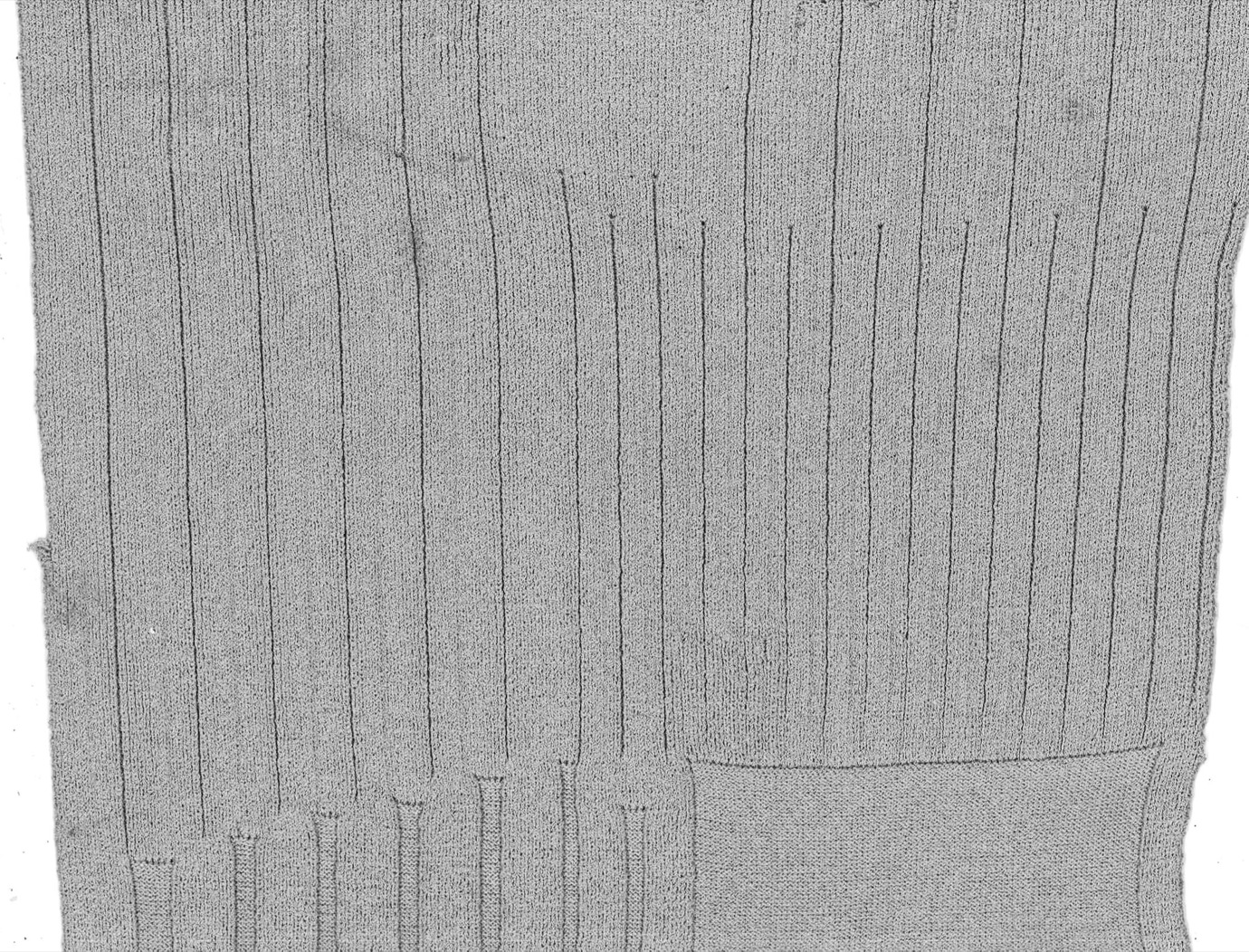

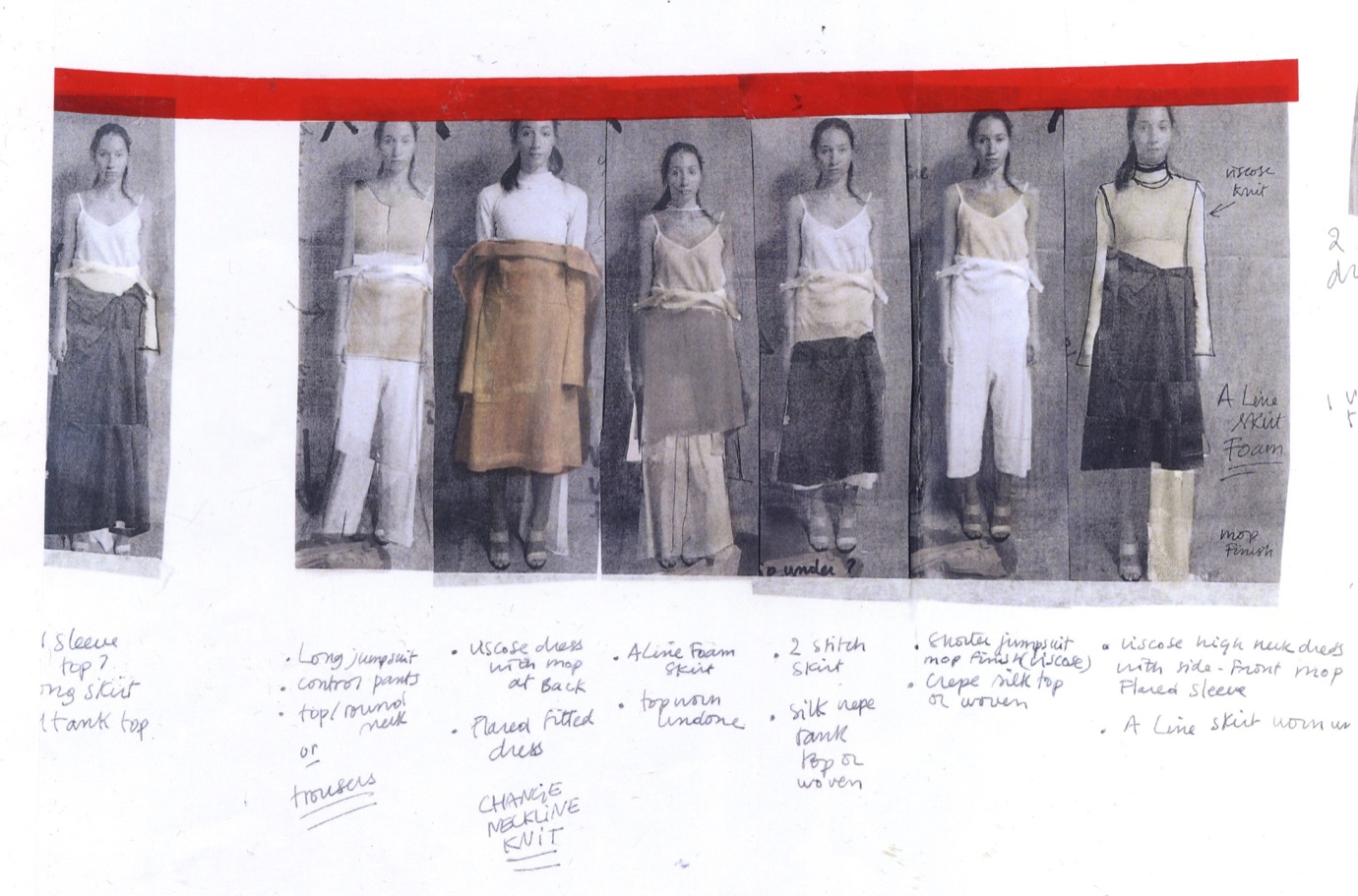

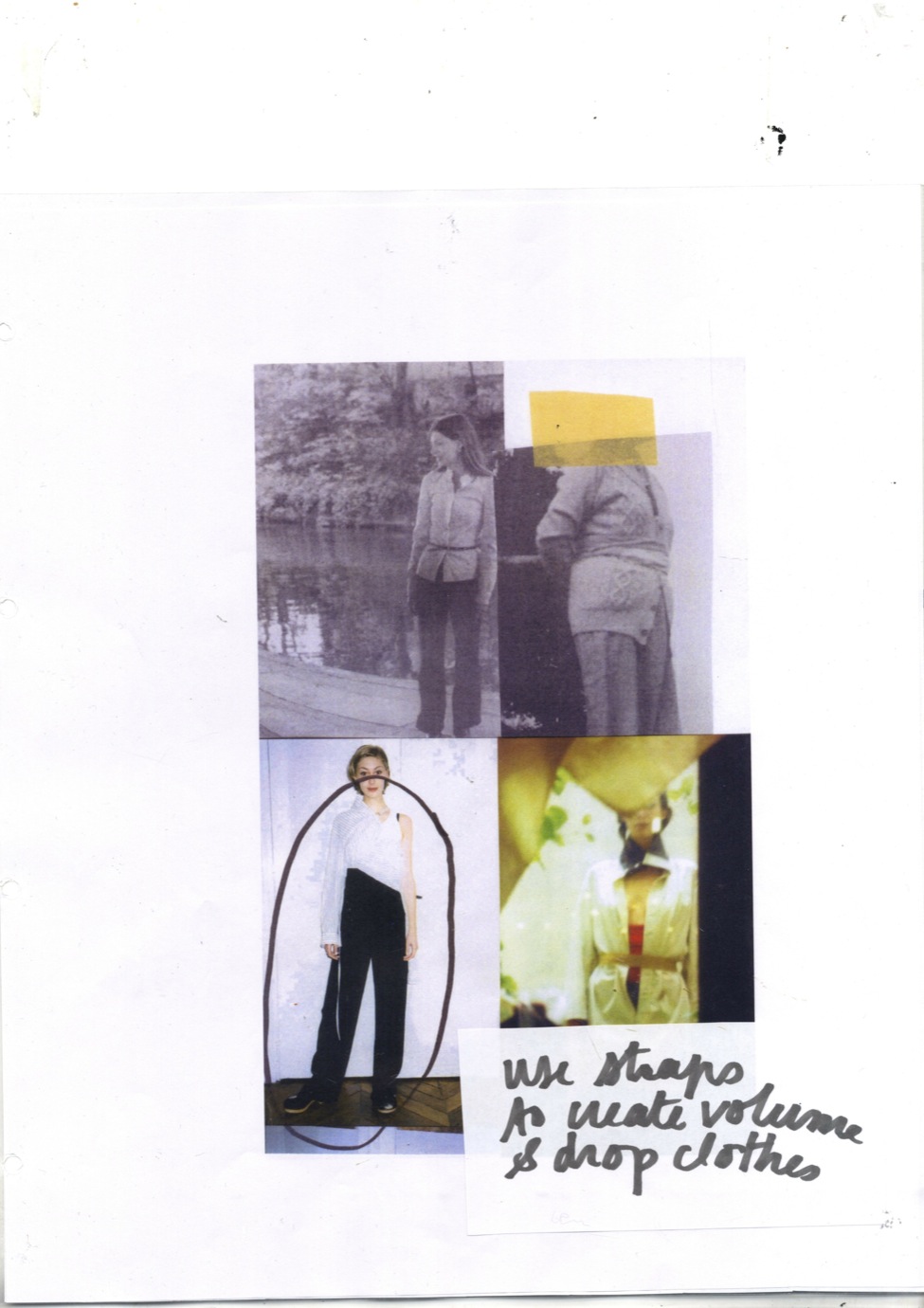

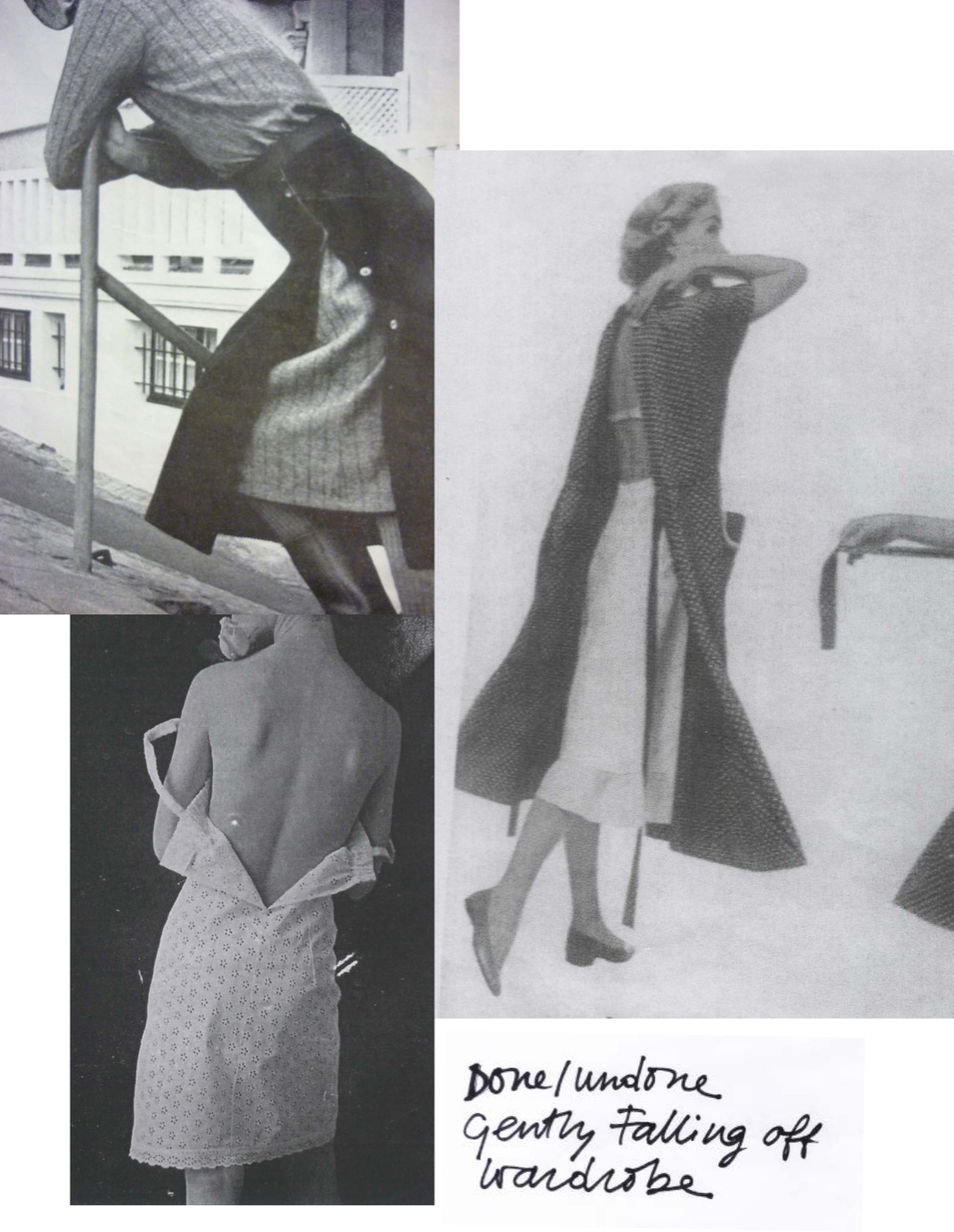

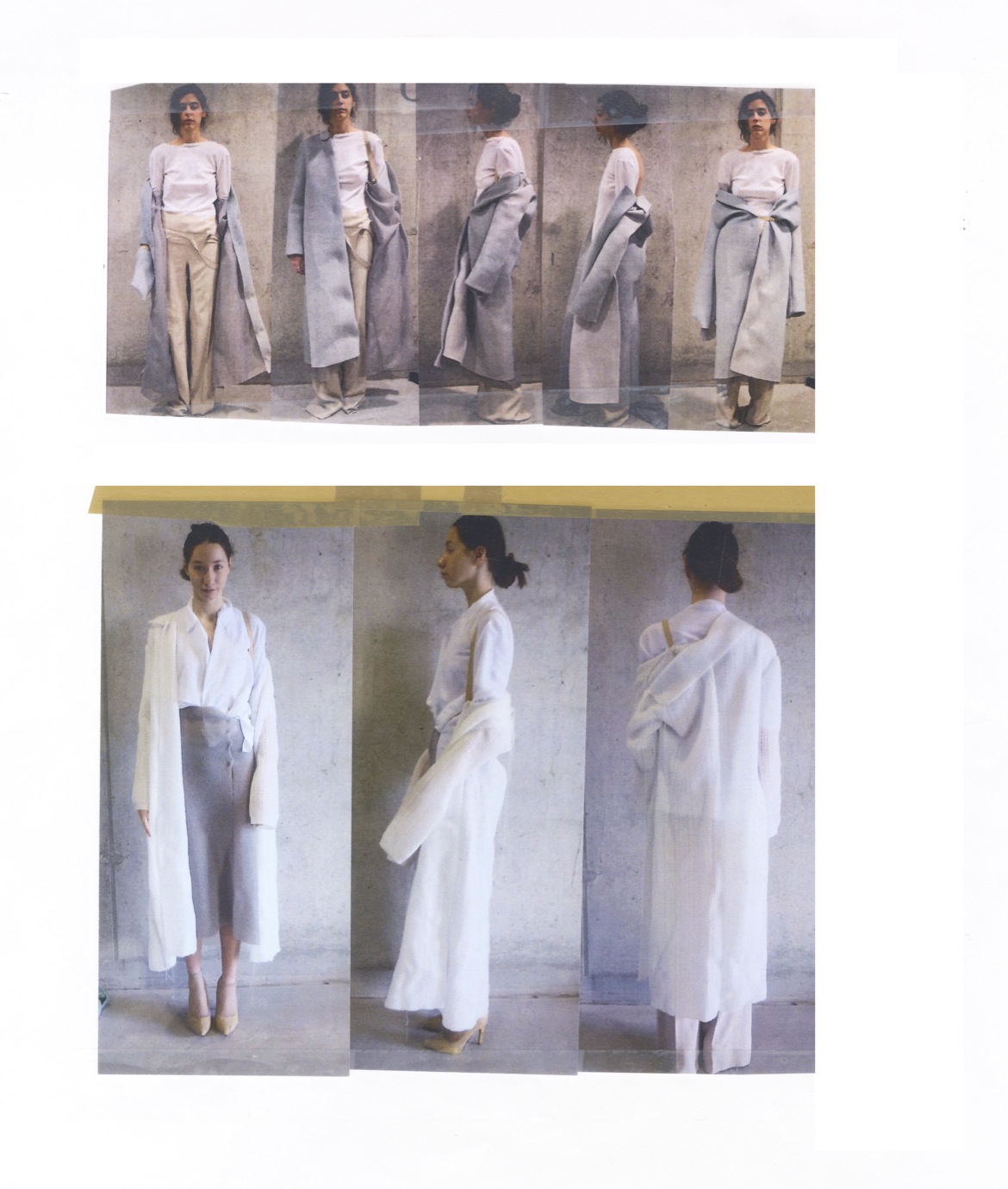

Amélie was particularly drawn to the graphic scenes where Jeanne changes clothes, and she started developing her collection around the concept of getting dressed. With a meticulous eye for detail and through hours of styling and restyling, Amélie created silhouettes on the verge of being undone: the loose knit sweater hanging largely over the model’s shoulder, the buttons of her pants and jacket wide open, barely holding onto her body with elastic straps.

The silhouette on the verge of being undone shows a woman on the edge of explosion. By reworking the character of the desperate housewife, Amélie makes her audience pay attention to something so recognisable, yet so often ignored. This woman is not fierce or glamourous or powerful, she is real. “I sound like an old grandma, but I think some collections are not showing women in a respectful way. They seem to feel powerless and full of anger. I think there is something lacking in the fashion world today.”

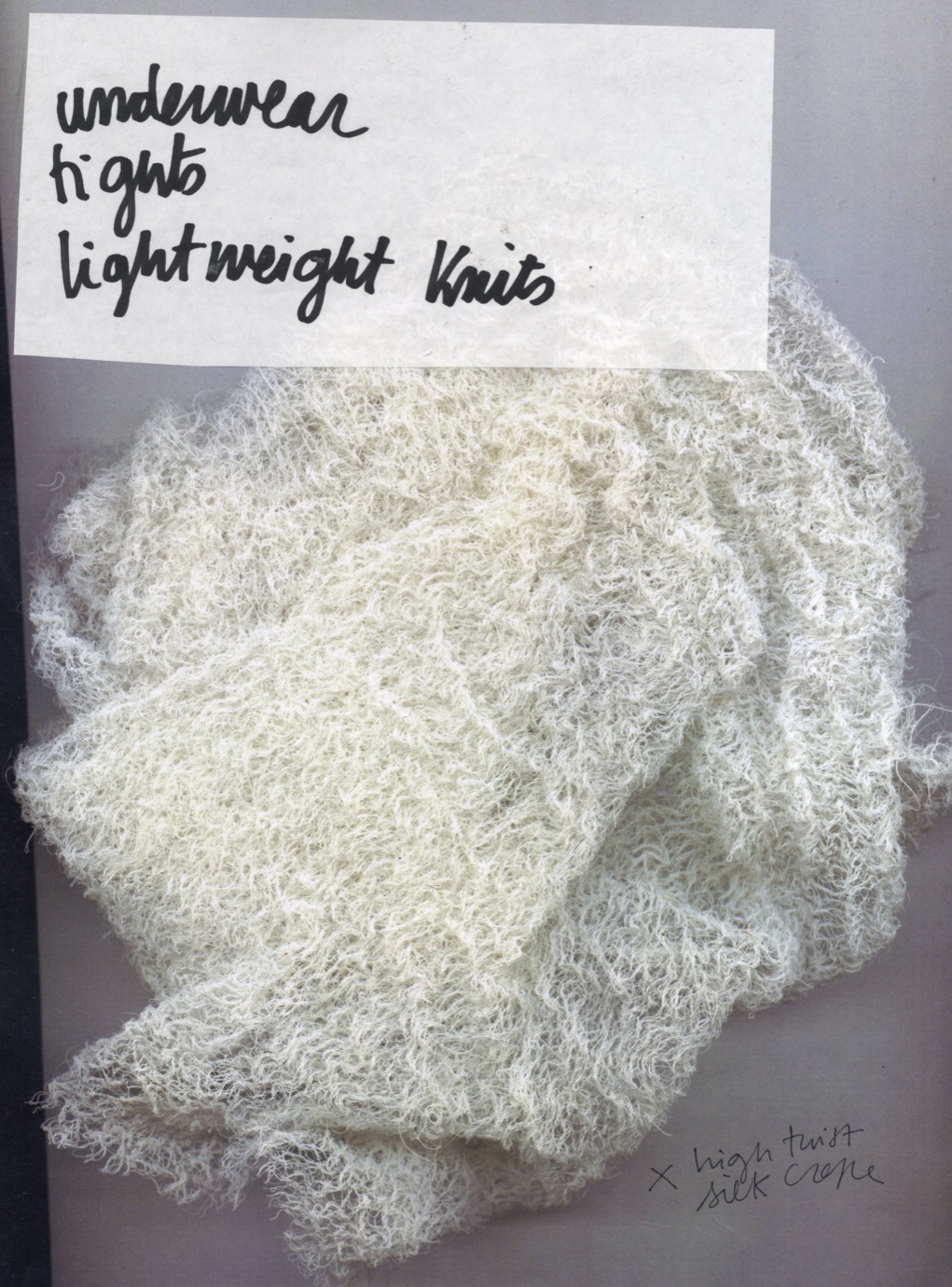

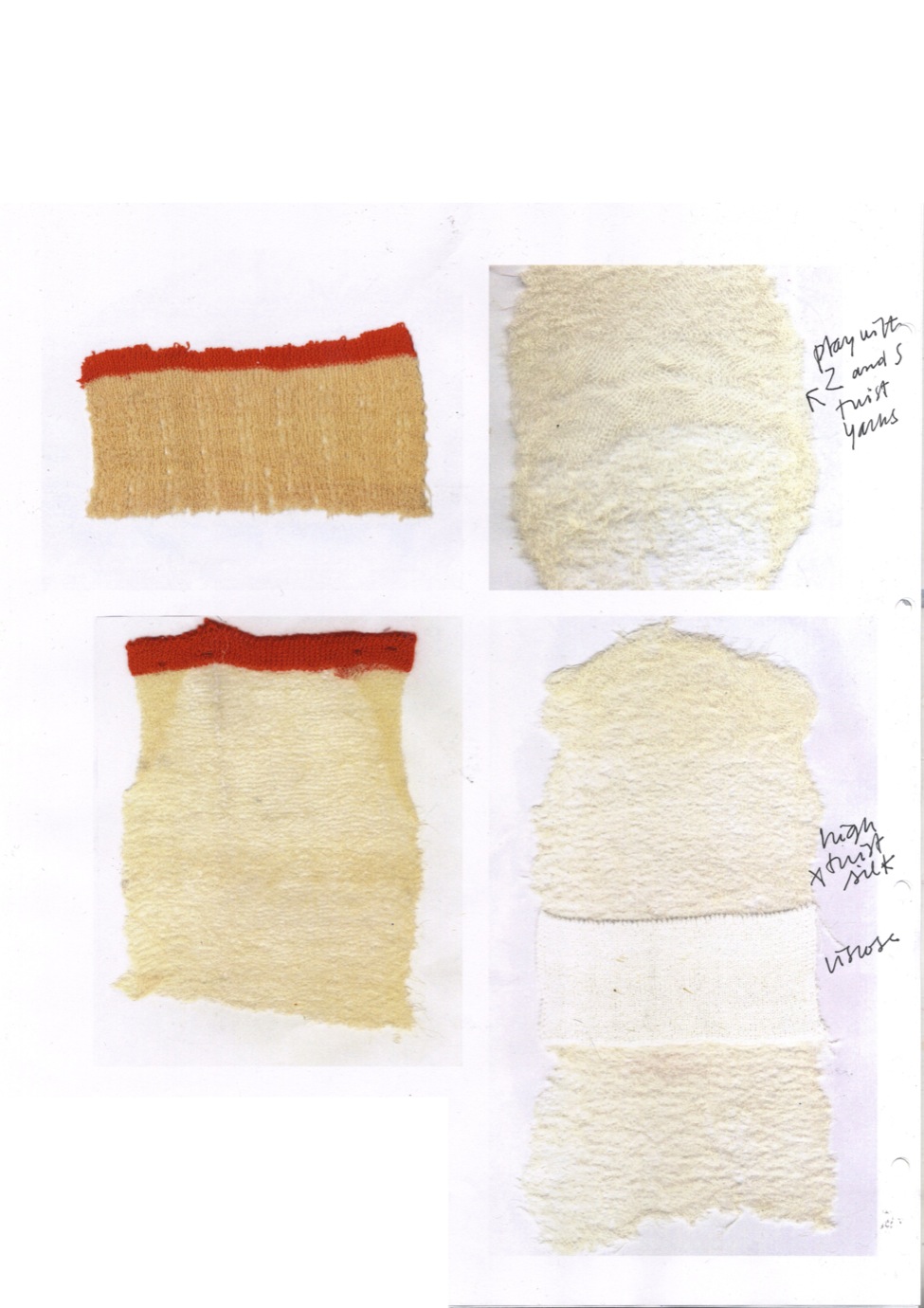

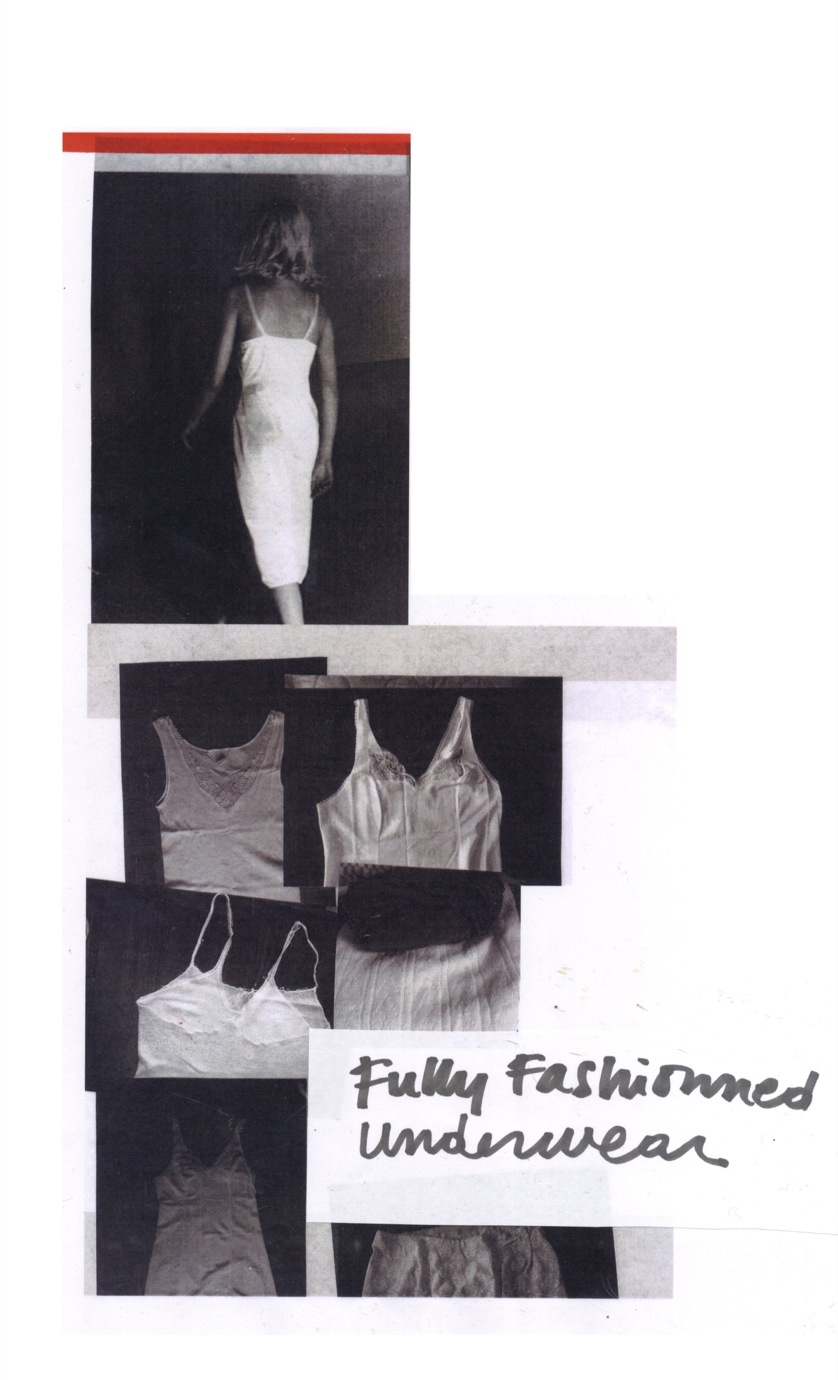

However, this doesn’t mean that her woman isn’t attractive. Amélie kept wondering “how to reveal the underwear in a way that is not sexy but sensual”, looking to reclaim the beauty of this forgotten woman. The result is an effortless attraction, a French sensuality, grown out of subtle suggestion. “This woman is sensual without trying to be.” Long hemlines and heavy knits are combined with see through fabrics and naked shoulders to achieve that accidental elegance.